Role of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the spread of Deobandi ideology in Pashtuns – by Abdul Nishapuri

Related posts: Why are Pashtun nationalists mute on Deobandi ideology and identity of TTP-ASWJ terrorists? – See more at: https://lubpak.com/archives/306125

Editorial: What is Pashtun nationalism? https://lubpak.com/archives/301247

Historical context and roots of Deobandi terrorism in Pakistan and India https://lubpak.com/archives/306115

Ahmad Shah Durrani Abadali and Shah Waliullah: Pioneers of Shia Genocide in Subcontinent https://lubpak.com/archives/306269

This post, based on historical evidence, shows an inadvertent role played by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan) in the spread of Deobandi madrassahs and ideology in the Pashtun areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (formerly NWFP) province of Pakistan and the adjoining tribal areas (FATA). The aim is not to suggest that Bacha Khan himself was a sectarian Deobandi bigot, but to highlight an error of judgement on the part of a progressive leader in ignoring the inherent takfiri and intolerant nature of the (semi-Salafi) Deobandi idelogy and prioritizing it over more inclusvie Sunni Sufi/Barelvi strand of Islam.

It is our considered view that peaceful and tolerant Pashtun ethnicity must not be amalgamated with the takfiri Deobandi and Salafi/Wahabi ideologies which were imported in Pashtun areas (and other areas of Pakistan) in the last 150 to 200 years. Indeed, the problem doesn’t lie with the Arab, Punjabi or Pashtun ethnicity, the probelm of takfiri violence in the world of Islam is to do with the takfiri Jihadist ideologies inherent in the Deobandi and Salafi/Wahabi schools.

Pashtuns form the single largest community in Afghanistan, consisting of approximately 38% of the population.[1] Pakistan also hosts a significant Pashtun population, primarily in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP, new name Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), where they make up 78% of the population, and in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), where they make up 99% of the population.[2] Overall, 15% of Pakistanis are Pashtun.[3]

Since its formal inception India in mid 19th century, Deobandi revivalist movement is notorious due to its inclination to Salafi/Wahabi strand of Islam, sectarian intolerance, violence and Jihadism. Particularly, since late 1970s, Deobandi seminaries (madrassas), clerics and religio-political groups in Pakistan have become increasingly radicalized due to generous Salafi/Wahabi funding from Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries and institutional support of Pakistani, American and Saudi intelligence agencies. Deobandi Jihadi proxies have been used by Pakistan army in Afghanistan and Kashmir. In return, Deobandi clerics (ulema), seminaries and parties have enjoyed excessive power, money and monopoly of violence. Today, Deobandi militant groups in Pakistan (variously operating as TTP, LeJ, ASWJ, JeM etc) are involved not only in massacres of Sunni Barelvis, Shias, Hindus, Christians and Ahmadis, they are also responsible for massacres of secular and nationalist leaders and activists. Deobandi terror outfits are now an active part of Al Qaeda, Taliban and are known to operate in countries as diverse as Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Bahrain and Syria.

When developing a strategy involving the Pashtun community in Afghanistan and Pakistan, it is relevant to understand the Deobandi sub-sect of Sunni Islam (which must be differentiated from Sunni Barelvis/Sufis, the majority Sunni sub-sect in India and Pakistan). Deobandi Islam is the most popular form of pedagogy in the Pashtun belt on both sides of the Durand Line that separates Afghanistan and Pakistan. Moreover, prominent Afghan and Pakistani Taliban leaders have studied in Deobandi seminaries.

In 1867, Darul Uloom was founded in the town of Deoband, India, as one of the first major seminaries to impart training in Deobandi Islam. The Darul Uloom Deoband claimed to inhert the Darul-Harb (place of war) type Jihadist ideals of Shah Waliullah, Syed Ahmed and Shah Ismail. It participated in several non-violent and violent movements to undermine the British rule in India. It was equally active in denouncing Sunni Barelvis/Sufis, Shias, Ahmadis, Hindus and Christians.

The Deobandi movement became the most popular school of Islamic thought among Pashtuns living on both sides of the Durand Line. Ironically, a key role in the spread of Deobandi ideology was played not only by Deobandi clerics such as Maulana Mufti Mahmood and Maulana Abdul Haq but also inadvertently by secular leaders such as Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (aka Bacha Khan).

Many prominent Pashtun community leaders established Deobandi seminaries in Pashtun areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a prominent Pashtun leader, was instrumental in establishing several schools based on Deobandi curriculum in the Pashtun belt.[10]

This post will help in understanding why many Pashtun nationalist and secular friends, who legitimately criticize Punjabi military establishment and Saudi Salafi ideology, remain generally mute on common Deobandi hate ideology of the TTP-ASWJ terrorists who are not only killing Shias, Sunni Barelvis, Christians etc but are also involved in massacres of secular and nationalist Pashtun activists and leaders. As a matter of fact, most Pashtun nationalist freinds not only remain mute on Deobandi hate ideology, they hardly clearly name and condemn ASWJ or Sipah-e-Sahaba, the takfiri Deobandi terrorist group responsible for massacres of Shias and Sunni Barelvis.

We are of the views that by founding and supporting Deobandi madrassas, Bacha Khan, at least inadvertently contributed to a movement which is currently fully demonstrating itself in the shape of takfiri Deobandi terror groups. It seems that Bacha Khan ignored the local Pashtun population’s adverse reaction to the semi-Salafi Jihadist movement of Syed Ahmed and Shah Ismail in Balakot and Swat. Syed Ahmed and Shah Ismail tried to enforce semi-Salafi takfiri Islam on local population, tried to curb Sufism and ban Pashtun cultural traditions and ceremonies, festivals etc. Both of them were killed in 1831 by local Sufi-oriented Pashtuns who did not accept the puritancial takfiri clerics.

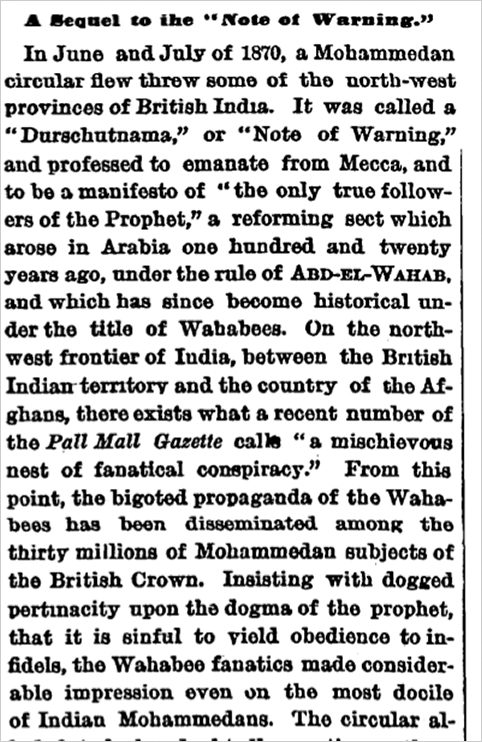

In the subsequent decades, the Salafi-Wahhabi and semi-Deobandi influences started becoming more visible in the North Western Fronter Province (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). Here, from arvhive of New York Times, nearly a century and a half ago (1872), a stark warning of the emergence of a “mischievous nest of fanatical conspiracy” – a Salafi/Wahabi and Deobandi nest whose beliefs are similar to those of the Taliban and Al Qaeda – around the northwestern frontier of British-ruled India and Afghanistan. That is to say, modern Pakistan.

Wahhabi Fanatics Reported on the Afghan Frontier Feb. 13, …1872

By Stephen Farrell

http://atwar.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/02/13/wahabbi-fanatics-reported-on-the-afghan-frontier-today-february-13-1872/

However, Bacha Khan ignored to protect the traditional, non-puritanical aspect of the Pashtun society, and instead preferred to invest in Deobandi ideology and madrassas, instead of Sunni Sufi/Barelvi or secular schools. This misjudgment on his part had immense costs for peaceful Pashtun cluture and society in subsequent decades. Bacha Khan and traditional Deobandi clerics played a role in the spread of Deobandi ideology in tribal areas and N.W.F.P.

Moreover, Bacha Khan also extended support to the semi-national semi-Salafi Jihadist the Faqir of Ipi who resorted to violence to defend an exaggerated sense of Pashtun nationalism built on forced conversion and marriage of a Hindu girl to a Pashtun Sunni Muslim.

Due to its inherent violent nature (ignored by Bacha Khan), the Deobandi ideology was always attractive to Saudis and Salafi/Wahabi clerics who made sure that Pashtun society is increasingly radicalized by Deobandi and semi-Salafi ideologies. A radicalized Deobandi society in at least some Pashtun areas today lacks the tolerance and diversity that was seen in other Pashtun and non-Pashtun areas where Sunni Barelvi/Sufi and Shia ideologies were allowed to flourish. For example, Saudi Salafis and Pakistani establishemnt could not radicalize the Parachinar population because of the inherent reluctance of Shia Pashtuns towards takfiri Jihadism and violence.

[1] See the UNHCR Assessment for Pashtuns in Afghanistan, located at www.unhcr.org/refworld/country,,MARP,,AFG,4562d8cf2,469f3a5112,0.html.

[2] “Population by Mother Tongue,” 2006 Pakistan Census Report, Pakistan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs and Statistics, available at www.statpak.gov.pk/depts/pco/statistics/other_tables/pop_by_mother_tongue.pdf.

[3] Ibid. Other Pakistani provinces host sizeable Pashtun populations: Baluchistan Province (29.84% Pashtun), Sindh Province (4.19% Pashtun), Punjab Province (1.16% Pashtun), and Islamabad (9.52% Pashtun).

[10] Sayed Wiqar Ali Shah, “Abdul Gaffar Khan,” Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad, undated, available at www.baachakhantrust.org/AbdulGhaffarKhan.pdf.

http://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-past-and-future-of-deobandi-islam

In his personal life, Bacha Khan was a devout Deobandi Muslim. He set up several Deobandi madrassas and went to hajj on five different times. Bacha Khan was so religious that he sent his eldest son Ghani Khan to a Deobandi darul uloom. However, Ghani Khan, after seeing the intolerant and ignorant mentality of Deobandi Mullahs, started criticizing them.

In 1910, Ghaffar Khan opened a Deobandi mosque school at his hometown, Utmanzai with the assistance of Maulvi Abdul Aziz. The school was temporarily closed down by the British authorities in 1915.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan commenced his social activities by setting up Deobandi madrassas and came into close contact with another social reformer of the area, Haji Fazli Wahid, popularly known as the Haji of Turangzai. Their combined efforts resulted in the opening of Deobandi seminaries (madrassas) called the Dar ul Ulum at Utmanzai and Gaddar (Mardan) in 1910. Apart from religious education, students were imparted the concept of patriotism. No details are available about the exact number of these Deobandi Madrassas or the number of students and teachers and the source of their income.6 The two were joined by some other Pashtoon intellectuals, particularly Maulvi Fazl-i-Rabi, Maulvi Taj Mohammad, Fazal Mahmood Makhfi and Abdul Aziz, most of whom were the graduates of Deoband.7 Abdul Ghaffar Khan was also in touch with Maulana Mahmood ul Hasan, the chief divine at Deoband and his pupil Ubaidullah Sindhi, who played a leading part in anti-British movements. They were then planning the establishment of an anti-British centre, deep inside the tribal area, but it did not materialise for the time being.8

6 Sayed Wiqar Ali Shah, Ethnicity, Islam and Nationalism: Muslim Politics in the North-West Frontier Province 1937-1947 (Karachi, Oxford University Press, 1999-2000), p. 18.

7 D. G. Tendulkar, Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bombay, 1967), p. 22.

8 Ghaffar Khan, Zama Zhwand au Jaddo Jehad (Pashto) (Kabul, 1983), pp. 94-107.

http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/studies/PDF-FILES/Shah-4%20new.pdf

http://www.baachakhantrust.org/AbdulGhaffarKhan.pdf

As education was free and the Madaris were open to all communities, soon these madrassas got popularity and the number of students increased from 140 to 300. A silent converstion of Pashtuns to Deobandi ideology was taking place. 21

http://www.baachakhantrust.org/AbdulGhaffarKhan.pdf

In 1921, Ghaffar Khan founded Anjuman-e-Islah-e-Afghana The stated objectives of the Anjuman included: promotion of unity amongst the Pashtoons, eradication of social evils, prevention of lavish spending on social events, encouragement of Pashto language and literature, and creation of ‘real love’ for Islam among the Pashtoons. On 10 April, 1921, the first branch of Azad Islamia Madrassa was opened at Utmanzai, followed by many more branches in different areas of the Peshawar Valley. No accurate figures are available about the exact number of these schools but a careful study suggests that they were as many as 70. The curriculum included teaching of the Holy Quran and Hadith, Fiqh, Islamic history, Pashto, Mathematics, English and Arabic.

http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/studies/PDF-FILES/Shah-4%20new.pdf

In 1913, Ghaffar Khan participated in a congress sponsored by self-defined progressive Muslims, in the city of Agra. There he met several Deobandi and Salafi leader including Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (the Salafi Deobandi leaning leader of Indian National Congress), who later served as President of the Indian National Congress.

In 1914, in a similar congress in Deoband, Abdul Ghaffar took the suggestion of working with the people of the Northern mountain range (North West). He travelled to Bajaur (tribal area) for that purpose. In those lands he was faced with the most extreme forms of domination that the British authorities imposed on the Muslim population of the North, particularly the Pakhtun, who were obligated to make public courtesies to any English citizen they encountered. His experiences in Bajaur shook Abdul Ghaffar deeply. He decided to go into seclusion in one of the small (Deobandi) mosques of the region. There he began a long chilla (a spiritual retreat in the Islamic tradition, which includes fasting).

http://abdulghaffarkhan.blogspot.co.uk/2008/02/biographical-data-on-abdul-ghaffar-khan.html

In 1913, Ghaffar Khan met with some leading nationalist leaders including the ulema of the Deoband seminary, who in early 1914 decided upon forming two centers for the struggle of independence, one in India and the other in the tribal territories of the frontier. To this end they decided to prepare an army, not necessarily unarmed and nonviolent. But before this plan could be executed, his Azad Madrassas were closed down and Khan faced an extended crackdown in the area brought about by the foreign rulers.

http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/king-without-a-throne/

Abdul Ghaffar Khan also played a main role in the Deobandi-led Khilaft movement which played a key role in radicalizing of Deobandi and Salafi communities in India. The year 1919 saw India in turmoil; the economic situation had deteriorated; industrial workers were resentful of the working conditions, and the peasants were unhappy over general price-hike. The Muslims were deeply concerned about the treatment meted out to Turkish Caliph by the Allied Powers and the ‘nationalists’ were agitating over the ‘broken promises’ made during the course of War. To curb the ‘seditious’ and revolutionary activities in the country, the Government of India had decided to enforce the Rowlatt Act. It immediately roused a storm of protest. On 6 April, a successful all-India hartal was observed. In the NWFP, like the rest of India, protest meetings were held against the Rowlatt Act. Abdul Ghaffar Khan held a protest meeting at Utmanzai, attended by more than 50,000 people. In the rural areas of the Frontier, this was the first political occasion when such a large number of people participated to express solidarity on an all-India issue.9

Badshah Khan met Mohandas Gandhi in 1920 at a Khilafat conference in Delhi, heralding the mutual cooperation between the two and their friendship over close to three decades.

The provincial authorities could not remain a silent spectator of anti-British activities in the settled districts of the NWFP. Abdul Ghaffar Khan was immediately arrested and imprisoned, followed by a punitive fine of Rs. 30,000 upon the villagers of Utmanzai. Over a hundred and fifty notables were kept in confinement as hostages, until the fine was paid.10 After six months, Ghaffar Khan was released and allowed to join his family.

Already towards the end of 1918, the Khilafat movement had been launched in India. An offshoot of the Khilafat movement was the Hijrat movement. The Ulema declared India as Dar ul Harb (Land of War) and advised Muslims to migrate to Dar ul Islam (Land of Islam). Afghanistan, the neighbourly Muslim country with whom they had religious, cultural, political and ethnic ties, was deemed to be a safe destination. Amanullah Khan, the anti-British Amir of Afghanistan, offered asylum to the Indian Muslims. Eventually, more than 60,000 Muhajirin took shelter in Afghanistan. As Peshawar was the main city on the way to Afghanistan, it became the hub of the movement. Soon, it became impossible for the Afghan government to facilitate the settlement of these religious zealots in Afghanistan.11

http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/studies/PDF-FILES/Shah-4%20new.pdf

In 1920, Bach Khan went to Delhi to attend the Khilafat conference. In the same year, Provincial Khilafat Committee was reconstituted and Abdul Gaffar Khan was appointed as its president. He collected funds in the NW Frontier Province for the Khilafat cause. He, then, migrated to Kabul as a part of the Khilafat/ Hijrat movement.

http://www.baachakhantrust.org/Chronology%20of%20Baacha%20Khan.pdf

Abdul-Gaffar khan, during his visit to India in 1969, addressing the students of Darul-Uloom, said:-

“I have had relation with Darul-Uloom since the time the Shaikhul-Hind Maulana Mahmood Hasan was alive. Sitting here we used to make plans for the independence movement as to how we might drive away the English from this country and how we could make India free from the yoke of slavery of the English. This institution has made great efforts for the freedom of this country”.

http://darululoom-deoband.com/english/aboutdarululoom/freedom_fight.htm

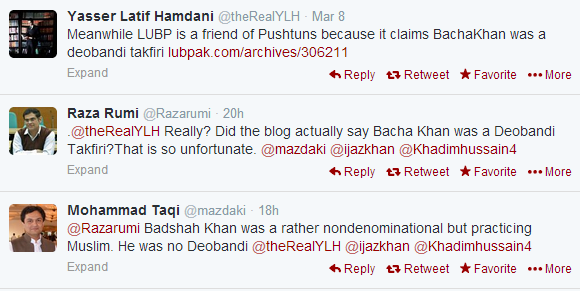

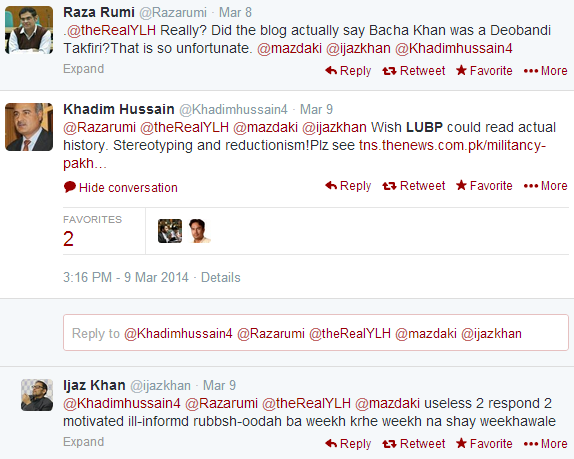

Reaction on Twitter

From facebook (Abdul Nishapuri)

From the Banu Umayya tribe of Arabian peninsula to the Pashtun tribes of Pakistan and Afghanistan to the Punjabis of Jhang, it is not the Arab, Pashtun or Punjabi ethnicity which is to be blamed. It is the violent, intolerant ideology (Sufyanism of Umayyads, Takfirism of Khawarij, Salafism of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab and Deobandism of Pakistan/India) that is responsible for brutal beheadings, organ-eatings and graphic inhumanities against non-Deobandi, non-Salafi Muslims and non-Muslims. Those who are ignoring the inherent violent nature of the Salafi and Deobandi ideologies are missing the whole point. Of course, the US, Saudi and Pakistani intelligence agencies played a key role in prostituting the Deobandi and Salafi ideologies and clerics for their strategic agendas but the very selection of these prostitutes was not a coincidence.

————

In Quetta, they try to hijack it as Hazara genocide, in Karachi, they try to hijack it as Muhajir genocide, in KP and FATA, they try to hijack it as Pashtun genocide. Why is it so difficult to admit that there is a country-wide Shia genocide by Deobandi terrorists of all ethnic backgrounds (including Pashtuns, Punjabis, Balochs etc), the same takfiri Deobandi terrorists (variously named as TTP, ASWJ, LeJ, JeM etc) who are also killing Sunni Barelvis, moderate Deobandis, Christians, Hindus, Ahmadis etc. Only today, three Shia professionals were target killed in two separate incidents in Karachi while yesterday in Kohat at least 10 Shia Muslims were butchered along with two ordinary/moderate Deobandis by the Deobandi ASWJ-TTP terrorists. Also today, there was an attack on Iran’s consulate in Peshawar and the sectarian motives of the attack were clearly stated by the perpetrator Major Mast Gul Deobandi of ASWJ-ISI. There is a consistent attempt by many right-wingers (Islamists) and secular activists to hide, dilute or rationalize the common Deobandi identity of terrorists across Pakistan. It is not in Pashtun or Punjabi ethncity, the evil resides in Deobandi ideology which is now as intolerant and violent as is the Saudi Salafi-Wahhabi ideology.

——–

There’s a difference between “almost all terrorists are Deobandis” and “all Deobandis are terrorists”.

We do NOT claim that all Deobandis are terrorists. Nor do we say that they are only killing Shias. We say that in almost all incidents of Shia genocide and Sunni Barelvi genocide, Deobandi terrorists are involved. They are also a dominant player in massacres of other communities. For example, Deobandi terrorists were involved in the Ahmadiyya massacre in Lahore (May 2010) and Christian massacres in Lahore (2008-13) and Peshawar (2013). They also kill those very few Deobandi clerics who challenge TTP or ASWJ’s power, discourse or agendas. When ordinary Deobandi folks are killed in the streets or markets by Deobandi terrorists, they are not killed due to their faith. When Shias, Sunni Barelvis, Christians or Ahmadis are killed, they are specifically targetted due to their faith.

Statistical data proves that Deobandis have the most dominant role in terrorism.

“The network of sectarian violence in Pakistan has its roots in the Deobandi sect. Syed Ejaz Hussain, who is a deputy inspector general of police, for his doctoral thesis in criminology at the University of Pennsylvania analysed the demographic and religious characteristics of the 2,344 terrorists arrested between 1990 and 2009 in Pakistan*. These terrorists were the ones whose cases were forwarded to the courts after the police were satisfied of their guilt based on their preliminary investigation. The sectarian breakdown of the arrested terrorists revealed that more than 90 per cent were of the Deobandi sect. An ethnic breakdown revealed that 35 per cent arrested terrorists were Pashtuns who in fact make up only 15 per cent of Pakistan’s population. http://www.dawn.com/news/664029/an-incurable-disease”

Unless this data is replaced by a more credible data, we will have to use it. Anecdotal evidence to contrary has limited value.

Moreoever, the victim communties’ (Sunni Barelvis and Shias in particular) own accounts or/and databases too point towards the Deobandi identity of perpetrators of violence. Check for example the Shia genocide database maintained by Shaheed Foundation, SK, LUBP etc. The Subalterns do speak!

Lastly, some friends assert that “The fact is not all Deobandis are involved in this genocide.” Our question is: are all Sunnis or all Salafis/Wahabis involved in this genocide? Is there a more precise identifier and marker than Deobandi terrorists (or takfiri Deobandi terrorists)?

Can anyone enlighten, please?

Some Pashtun and Deobandi including Pashtun Deobandi friends are extremely upset due to our posts on Ahmad Shah Durrani, Shah Waliullah and Bacha Khan.

If we can criticize Jinnah, Bhutto, Khamenei, Zardari, Imran Khan, Munawar Hasan, Shaheedi etc why can’t we critically evaluate Bacha Khan, Ahmad Shah Durrani and Shah Waliullah? History, my friends, is more sacred than our political, ethnic and/or religious heroes. Academic and historical inquiries are feared and discouraged by insecure minds.

Dear Sister Sarah,

Thanks for your in-depth, yet bit emotional analysis. Most of the points you raised above are, to some extent, right. But, without dealing the symptoms we’ll not be able to cure the disease. The subject needs a further detailed study. I would like to draw your kind attention to some of the aspects that you somehow missed to shed a further light upon:

i. Without understanding the role of British “masters” and the education system that they have imposed upon the Indians, especially the Muslims of subcontinent, we cannot do justice to the dilemma that we are facing today.

ii. During the Raj, tribal areas, being the buffer zone between the Soviet Union and British India, HAD to be radicalised. Why? I think it’s obvious.

iii. It is true that most members of the radical and banned outfits are so-called Deobandis. It is also a fact that these terrorists have caused damage to the minorities such as Ahmadis and Christians, including Shia Muslims, throughout Pakistan. But, we should not forget the fact that MAJORITY of the innocent people that these so-called Deobandis have assassinated belonged to the Deobandi school of thought. Even today, most people being killed in KP and tribals areas are Deobandis. So, it is true that some or more terrorists were born as deobandis, but after having fought against soviet union with arabs on their side, they have adopted salafism and takfirism as their ideology. From Tribal areas to Baluchistan, KP, Sindh and even Afghanistan Deobandis themselves have had the worst blow than anyone else. The problem in Pakistan is that everyone is talking about only their sect and group, not as a united voice, that is why it is has become easier for the wolves to devour all one by one.

iv. When sectarianism in Pakistan is discussed, then we should be more careful than making any emotional statements because it can further divide our society which is already at the verge of a civil war.

The roots of sectarian violence is not a Deobandi by-product. It is rather more of a political rivalry between Arabs and Iran. Every sane person in Pakistan is well aware of the fundings coming from both sources. There are no Deobandis in Iraq, Syria or Lebanon for that matter but everyone knows about the strategic interests of both Iran and the gulf states there.

regards

Ahmed

v.

Brother Ahmed,

When TTP, ASWJ, LeJ kill Shias, Sunni Barelvis or Christians, they kill them due to their faith, because they consider them kafir, mushrik or murtad based on their faith.

When the same terrorists (TTP, ASWJ, LeJ) kill ordinary folks in KP and FATA, many of the victims are of course Deobandis, the vicitms are not killed due to their faith. Ditto when TTP-ASWJ-LeJ kill Pashtun nationalist leaders, such killings are not motivated due to faith differences. Of course, we don’t hear Kafir Kafir, Deobandi Kafir in their rallies but we frequently hear chants against Kafir Shias and Qabar Parast (Mushrik) Barelvis in their speeches and statements.

By 1913, Bach Khan was making visits to Deoband and Delhi, to set up Deobandi madrassas in N.W.F.P.

Rajmohan Gandhi. GGhhaaffffaarr KKhhaann. Nonviolent Badshah of the Pakhtuns.

New Delhi: Viking, Penguin Books, 2004; rpr. Penguin Books, 2008.

An interesting chapter in the period immediately before the partition of India is of the association of Khan brothers with the insurgency mounted by Faqir of Ipi. The history of NWFP’s tribal areas is replete with a charismatic Pushtun horseman with Quran in one hand and sword in the other. The valiant Pushtuns had been fighting against the British for more than half a century and Faqir of Ipi was the latest of these great Jihadist Deobandi/Salafi/Wahabi warriors to raise the banner of Pushtun nationalism with its dangerous blend of Islamic Puritanism. The Frontier Congress had – perhaps without any knowledge of Nehru who would have shot down an idea of this kind- long backed Faqir of Ipi. Col. Shah Pasand Khan, former ADC to Amir Amanullah Khan of Afghanistan and a member of the Muslim League national guards, wrote to Jinnah on 8th July stating “firstly a few days ago I heard of Abdul Ghani, son of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, who came to see the Faqir of Ipi in connection with the resolution passed at Bannu by the Congress in support of Pathanistan. Mr. Abdul Ghani crossed the border of British territory to meet Faqir of Ipi. Government authorities supported this move… I myself investigated the matter and found out that Faqir of Ipi was given 7 lakhs of rupees by Mr. Ghani to propagate for the Pathanistan… (Document 68 Jinnah Papers Volume III Pages 164-165).

In July Faqir of Ipi made his pronouncement. This announcement was reported by S M Rashid, a young Muslim Leaguer, in his letter dated 17th July as “Nobody is to participate in either Congress or Muslim League. Nobody is to violate the peace of the Hindus because have consented to pay the poll tax to me. Muslim Leaguers in this area (according to Shariat of Waziristan) are to be devoured by ..wolves. A reward of Rs. 4000 (Kabulis) for killing Habibullah Khan (a Leaguer) and special protection for the family of his killer”. Rashid went onto talk of about the Mullahs from Deoband on a special mission : “All these Mullahs are the true disciples of Maulana Hussain Ahmed Madani Deobandi… the second selves of Abul Kalam Azad and Hussain Ahmed Madani. The majority amongst them are the originators of the crusade of Waziristan… Khalifa-tul-Muslimeen Mir Hazar Deobandi… Maulvi Khanmir Khan Deobandi, Maulvi Qameruzzaman Deobandi, Maulvi Sardar, Maulvi Mohd Zaman, Maulvi Mohd Rahim, Maulvi Mohd Din, Maulvi Abdul Razzaq Maulvi Raz Mohammad, Maulvi Mohd Din Shah, Maulvi Khawaja Mir and Maulvi Fazl Din.” (Enclosure No.1 to No. 181, Jinnah Papers Volume III, Pages 465-467). These Ulema were reinforcements from the Jamiat-Ulema Hind and Darul-uloom- Deoband to create insidious propaganda against Pakistan and the Muslim League.

Maulvi Abu Sulaiman, an 80 year old veteran spiritual leader from Waziristan wrote to Zafar Ahmad Ansari “While I was in Delhi, I received a call from the Frontier that Congress agents were touring Waziristan, doing propaganda against the Muslim League, had succeeded in converting the Faqir of Ipi to their point of view … I learnt that a deputation of the Frontier Jamiyaat-e-Ulama had already met the Faqir who thereupon became a staunch enemy of Pakistan taking the Muslim League to be the agents of the British, he now considers war against Pakistan as the greatest service of Islam. The government of Afghanistan is also a party to this conspiracy. Its Minister of Interior, Sardar Muhammad Farooq, called a special meeting of tribal representatives and persuaded them to support Pathanistan in combination with Afghanistan, Khan Brothers and the Faqir of Ipi. He even directed them to kill any opponent of Pathanistan. It was after the meeting of the Deobandi Jamiyyat-e-Ulama deputation with Ipi that the latter ordered his general, Abdul Latif Khan, to attack Miran Shah.” ( No. 183, Jinnah Papers, Volume III, Page 471).

Reinforcing what he had written earlier, Sulaiman wrote again a week later informing Ansari of the activities of Faqir of Ipi and the Congress Party “On the night of 29th of Shabaan, the Faqir Sahib of Ipi without informing anyone left for Mount Shawal so as to pass the month of Ramadan in some secret place. It is his habit to remain hidden from his people for several months in a year. This creates an impression of piety… After Id, he intends to call a meeting of tribal representatives at Makin, a central town in the territory of the Mahsud tribe (centre of Deobandi ideology). His object at the meeting would be to convert Prince Fazluddin and his party to his own point of view- either by persuasion or by force… Prince Fazluddin is an old sympathizer of our party- Jamiat-e-Mujahidin Hind. He has great influence over the Mehsuds. But a large part of Mehsud tribes still belongs to Faqir of Ipi… The Agents of Afghanistan and the Congress are very busy here propagating the idea of Pathanistan… to fight Pathanistan we must take some precaution. We must not appoint to the Governorship of the Frontier any person belonging to this province. Some such person should be appointed Governor who can successfully fight the propaganda that the League is un-Islamic, agents of the English and centre of Qadianis, and that to fight it is the greatest service of Islam… to fight the propaganda of the Congress and its agents, a declaration of Islamic government is not so essential as the proclamation for the suppression of prostitution, gambling, and use of wine and other corrupt activities”. ( Note 229, Jinnah Papers Volume III Page 670-671).

There are several things to be noted here. One – Faqir of Ipi’s insurgency sounds remarkably similar to the insurgency mounted today by Baitullah Mehsud Deobandi, Hakimullah Mahsud Deobandi and Fazlullah Panjpiri Deobandi etc. Bach Khan family allied themselves with the Ipi insurgency because to them the cause of Pushtun nationalism was supreme and it did not matter to them that the mix of Pashtun nationalism with Deobandi semi-Salafi firebrand Islamic Puritanism was a dangerous mix (and a mix that even Pakistan’s military employed to its advantage in the first Kashmir war in 1948, the Afghan War and the Kashmir insurgency in the 1990s). Pakistani state’s diversion (partially supported by the US and the CIA) of the Islamically charged Deobandi Pushtun tribal nationalism to Godless Soviets and Hindu India is now drying out.

http://pakteahouse.net/2008/07/22/nwfp-history-4-faqir-of-ipis-uprising-and-the-frontier-congress/

Taliban roots in political and religious movements on Pashtun lands can be traced to the Salafi/Wahhabi-influenced movement of Syed Ahmed of Bareli (not to be confused with Barelvi/Sufi sect, but a father figure of Deobandis), who sought political control by declaring himself the vanguard of Islam, imposed centralised Sharia Laws, changing Pashtun traditions and norms with their version of Islam and challenging the traditional authority of Pashtun elders as well as the religious clergy by assigning themselves the authorities to arbitrate disputes and collect religious tax, as Zakat and Ushr. These steps by Syed Ahmed and his disciples from across India and among Pashtuns were rejected by the traditional Pashtun leadership as well as clergy. The alien movement ensued in an utter failure. However, thanks to Bach Khan and traditional Deobandi clerics investment in spread of Deobandi ideology, today KP and FATA is dominated by Deobandi and semi-Salafi ideology and madrassas.

http://durandline.wordpress.com/tag/bacha-khan/

Efforts at crafting narratives of foreign involvement as sole problem afflicting Afghanistan and the region (Soviets attacked, USA attacked, Punjabi establishment, Saudi Salafis etc) cannot hide the historical and ideological undercurrent of the Pashtun areas.

Faqir of Ipi had close relationship with Bacha Khan and it was Bacha Khan who kind of convinced him to stop his jihad against Pakistan. He died in 1960 and by the time he was not an active warrior. I don’t have the source now but I believe Bacha Khan also helped him get medical attention in Peshawar too.

Is Non-violence Bacha Khan’s legacy? While he took to non-violence as a creed, Zalmai Pakhtoon – a militant organization and wing of Red Shirts- was a decidedly violent organization founded by Ghani Khan, Bacha Khan’s son and which continued to operate way into the 1970s – with some blaming it for the famous assassination of Hayat Khan Sherpao. That Bacha Khan encouraged Fakir of Ipi’s militancy against Pakistan is a well known fact.

He stood for the continuation of the tribal traditions and way of life which accorded him and his family their sardari status. His philosophy was essentially a sort of tolerant Islamic Puritanism blended with Pushtun Nationalism, another not so tolerant variant of which was his friend Faqir of Ipi’s Islamically charged Pushtun Nationalism and that strain is still represented by Behtullah Mehsud and the like.

Faqir of Ipi (the forerunner of Behtullah Masood) was a staunch ally of Bacha Khan… Bacha Khan was releasing funds to Faqir of Ipi and his terrorist movement

On the reality of Bacha Khan’s non-violence and “tolerant” version of Islam please note that somehow Faqir of Ipi’s jehad against British, Hindus, Muslim League (which he called the bastion of Qadianism) doesn’t strike me as “non-violent” or “tolerant”. Bacha Khan was his biggest backer in NWFP.

Bacha Khan supported the Kashmir freedom struggle and supported the export of Waziri Mahsud and other tribal lashkars for freedom of Azad Kashmir.

Deobandi Taliban are a logical sequel to the Faqir of Ipi.

In 1936, a man named Mirza Ali Khan aka Faqir of Ipi launched an armed anti-colonial rebellion in British India in the tribal areas of the N.W.F.P. The Faqir of Ipi, had a reputation for saintliness but that was soon overshadowed by his exploits as an insurgent. That year, a 15-year-old Hindu girl married a considerably older Pakhtun man in an alleged love affair. Since the girl, who had the moniker Islam Bibi bestowed on her was a minor, her mothers approached the British for help and she was returned to her family. Khan (the Faqi of Ipi), who was from Waziristan, took this as an incitement against Islam and the Pakhtun tribes and launched a revolt that was able to withstand British military expeditions thanks to unorthodox guerrilla tactics. On April 14, 1936, a jirga held near Mir Ali declared jihad against the British. It decided to raise a tribal lashkar, with the Faqir of Ipi as its chief. He travelled to South Waziristan to gain support of the Mehsud tribe. Not unlike Deobandi Mujahideen or Taliban supported by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, the Faqir of Ipi too received support from both the Germans and the Italians providing him with weapons and funding during the WWII.

At the time, Khan was a legend for his military exploits; now he barely exists in the general consciousness. Sure, he was an anti-colonial figure on a par with any other, but his movement was spurred by a marriage that would now be seen as illegitimate. He preached a version of Islam that would be disdained as distinctly Deobandi Taliban-ian and had no hesitations in allying with the Afghan government or the Axis powers during the Second World War. Not unlike a few Deobandis (now becoming extinct) who revere Pirs, he too followed a Pir but was very puritanical in his approach to Islam, just like modern day takfiri Deobandis. Faqir of Ipi Khan is said to be the grandfather of senior Deobandi Taliban cleric Jalaluddin Haqqani known for terrorism operations in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Hafiz Gul Bahadur is also a descendent of Faqir of Ipi. Khan never reconciled himself to the idea of Pakistan and even declared himself president of the territory he inhabited after Partition. Simply put, being right on the central question of his time — the presence of the colonial British in the subcontinent — was not enough to make him an undisputed hero.

This brings us to the various Deobandi militant factions fighting under the Taliban rubric (TTP, LeJ, ASWJ, JeM etc). Stipulating from the start that the inhuman tactics of the Taliban are not to be condoned, it is instructive to compare it with the Faqir of Ipi for the way it fuses anti-imperial ideology with its depiction of itself as a religious vanguard.

Our need to instantly label the Taliban as a uniquely reactionary force that has no roots in history is undercut by the existence of past Pakhtun movements, like that of Mirza Ali Khan, the Faqir of Ipi. Just as the Taliban use suicide bombings as a weapon, Khan’s men were accused of castrating those they fought; both saw themselves as the last, best hope of saving Islam; and the British colonisers have been replaced by the imperialistic Americans and their predator drones.

We need to acknowledge the strain of religious nationalism that exists in both Faqir of Ipi and Taliban’s violent movements.

It is, therefore, important to dispel the ahistorical impression that the Taliban are an unprecedented evil, an externally crafted phenomenon with no basis and space in local history and Deobandi ideology. The natural human tendency to egotistically believe that what is happening right now is so very unique as to render history as a mere prologue leads to support measures, like military operations and US drone strikes that we would not consider otherwise. Unles the Deobandi and Salafi roots of the violent ideology are cut down, it will not be possible to tackle the menace of terrorism from FATA, KP and other areas of Pakistan.

http://tribune.com.pk/story/366427/the-faqir-of-ipi-and-the-taliban/

As written elsewhere, Taliban are historical heirs to Mullah Pawindah and Faqir of Ipi. The Deobandi Pashtun flirtation with puritanical Deobandi and Salafi/Wahabi Islam and violent resistance itself is historically linked to the Syed Ahmed’s Salafist “jihad” against Ranjit Singh’s Government in Lahore. Pawindah extended it against British Raj and Faqir of Ipi also attacked Pakistan as “unIslamic bastion of qadianism”. Bacha Khan supported the Faqir wholeheartedly which is where Pushtun nationalism amalgamates with Deobandi or Salafi ideology. And finally – the current leader of TTP – Gul Bahadur- is Faqir of Ipi’s grandson.

http://tribune.com.pk/story/366427/the-faqir-of-ipi-and-the-taliban/

Faqir of Ipi had not represented even the tribal Pashtuns, let alone all other Pashtuns of Pakistan or Afghanistan. He was an individual having the most minimal follower-ship. Distorting history in his name is a mere attempt to demonise already down-trodden and war torn pashtuns and adding to their miseries. In Parachinar, until a few decades ago, both Shia and Sunni Muslims lived together in a harmony and there are still many who had intermarriages and lived happily ever after.

So, again, the problem is not simple and therefore, blame game bears us no fruit but further spreads the hatred. To call a whole group of people, the majority, of a province or certain area, because of the crimes of only one percent or less of them, needs a lot of prejudice as a base.

There are those who point out that not all Deobandi and Salafi have subscribed to the takfiri/Kharijite ideology and action that is at the root of the violence and who attempt to separate the conservatism and fundamentalism of Salafism and Deoband from active violence against those outside their movements. Among them is the anti Kharijite/Takfiri site Takfiris.com, which provides this observation of the methods employed by the jihaddinst: “We have experienced over the past 15 or so years a pattern that seems to come only from Takfiris such as Hizb al-Tahrir, al-Muhajiroon, the Qutbis and their likes. They act like bandits and steal content from Salafi websites, remove all credentials and use this to deceive the people. & etc. at

http://www.takfiris.com/takfir/articles/bavkc-takfiri-dawah-thieves-the-derby-dawah-project.cfm

Takfiri Da’wah Thieves and Bandits: The Derby Da’wah Project

http://www.takfiris.com

good to know that the old days kafir bacha khan become radical muslim here as your post suggest to me , who he was it,s doesn,t matter to his followeer,s including me ….. may i ask one simple question … what you will say about massacres of khumani against sunni muslim in iran durring american backed revolution ? if it was right for him then it should be allowed to us as-well …… how much i know about bacha khan is simple that he was the lover of islam and pashtoon , he never fall him self in sectarian dispute,s throughout his life , he was the preacher of peace and pride ……… don,t say anything wrong in the veil of (takiya) against him nor your any post will do anything to his status ……… bacha khan was real king and real king never die they live for ever perhaps your post,s creating trouble for your own people among us ….. read last sentence one,s more…..

Sardar Khan,

Your irrelevant comments about Khomeini show your anti-Shia bigotry and confirm the thesis that many progressive posing Deobandi Pashtuns are no more than camouflaged Deobandi bigots.

@JIM

Not all Deobandis or Salafis are terrorists but almost all terrorists in Pakistan happen to be Deobandis and a few Salafis/Wahhabis.

According to an article written by MANSUR KHAN MAHSUD, BRIAN FISHMAN and Anand Gopal, Hafiz Gul Bahadur Deobandi is a descendant of the Faqir of Ipi.

Besides the Haqqanis, Hafiz Gul Bahadur is the most important Pakistani militant leader in North Waziristan. He is believed to be 45 years old and is from the Mada Khel clan of the Uthmanzai Wazir tribe, which is based in the mountains between Miram Shah and the border with Afghanistan. He is a resident of the village of Lowara and is a descendant of the Faqir of Ipi, a legendary fighter known for his innovative insurrection against British occupation in the 1930s and 1940s.[i] Bahadur is a cleric and studied at a Deobandi madrassa in the Punjabi city of Multan. Bahadur fought in Afghanistan during the civil war that followed the Soviet withdrawal and upon returning to North Waziristan became a political activist in the Islamist party Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (Fazel ur-Rahman), or JUI-F.[ii] He rose to prominence in 2004 following Pakistani military operations in North Waziristan and coordinates closely with the Haqqanis on both strategy and operations in Afghanistan.[iii] Today, Bahadur has more 1,500 armed men under his direct command.

http://southasia.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2010/04/23/inside_pakistans_tribal_frontier_north_waziristan

Bacha Khan and the Congress in NWFP were instrumental in the great game unfolding in 1947. They supported Faqir of Ipi’s rebellion in 1947 against the state of Pakistan. Faqir of Ipi had declared a Jehad on British Imperialism, Qadiyaniism and Pakistan. Faqir of Ipi’s direct descendant, Hafiz Gul Bahadur, is one of the leading lights of the TTP today and is most likely associated with the Ahrar-ul-Hind.

The idea is not to of course suggest that Congress or Bacha Khan or anyone else is responsible for the TTP as it exists today. Congress as a big tent organization just like the Muslim League had every right to co-opt as many groups as possible. What I have written in my previous blog and repeat here again is that a great majority of those Nationalist Muslims who opposed Jinnah and the Pakistan Movement did so out of sectarian motives and their hatred of Jinnah and Muslim League was exploited by the Congress Party.

Secondly there is an unbroken ideological link between Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam Hind and its anti-colonial pretensions as well as its sectarian outlook and the TTP which challenges Pakistan today. They share the same straitjacket religious ideology which seeks to limit Islam to a series of harsh punishments. Obviously they were happy to stay in a United India because they believed that ultimately they would convert all of India to Islam. They feared a Muslim majority nation state because they feared that it would be inevitably ruled by professional classes who had a very pragmatic relationship with faith. It was a question of intra-Muslim positioning. The TTP and its factions are quite clear that they see that imposing their point of view in even a sharia-compliant Pakistan is going to be hard so long as it follows representative democracy.

http://pakteahouse.net/2014/03/05/ahrar-ul-hind-ii-faqir-of-ipi-majlis-e-ahrar-and-the-ttp/

External and internal stereotypes about Pashtuns – by Nadeem F. Paracha – See more at: https://lubp.net/archives/307125#sthash.YxfDPi5X.dpuf

Deobandi Islamist militancy in Bangladesh and counter-narrative – by Muhammad Nurul Huda – See more at: https://lubp.net/archives/306833

The footprints of Deobandi militant jihad in India and Pakistan – by Maloy Krishna Dhar – See more at: https://lubp.net/archives/307525

بریلوی مسلک وہابی-دیوبندی نظریاتی یلغار کے نشانے پر ہے -برطانوی اخبار گارڈین – See more at: https://lubp.net/archives/302091

A research article on differences and similarities between Deobandis and Salafis/Wahhabis – See more at: https://lubp.net/archives/280211

Role of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the spread of Deobandi ideology in Pashtuns – See more at: https://lubp.net/archives/306211

Historical context and roots of Deobandi terrorism in Pakistan and India https://lubp.net/archives/306115

I believe that is among the such a lot vital information for me. And i am happy reading your article. But should remark on some common things, The website style is great, the articles is truly great : D. Excellent task, cheers

In 9 out of 10 instane, we in Parachinar, Hangu, Kohat and Peshawar are being killed by our own Pashtun brothers of Deobandi origin. Pashtun Shias must die at the hands of Deobandi Pashtuns of JUI, ASWJ, TTP while secular Pashtun Deobandis of ANP and PKMAP look the other way.

ولی خان کے سیکولر ازم کا بھانڈا کیسے پھوٹا – صدائے اہلسنت https://lubpak.com/archives/336631

Role of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the spread of Deobandi ideology in Pashtuns https://lubpak.com/archives/306211

عوامی نیشنل پارٹی کے مرحوم قائد ولی خان کے وہابی نظریات – از عبدل نیشاپوری https://lubpak.com/archives/336527

Innocent Deobandis, manipulative Pakistan army! https://lubpak.com/archives/331858

ANP and ASWJ condemn massacre of Shias in Peshawar: Do you know what’s common? https://lubpak.com/archives/331806

ANP’s discourse on Pashtun genocide – by Abdul Nishapuri https://lubpak.com/archives/315869

Conversation: Why are Pashtun nationalists mute on Deobandi ideology and identity of TTP-ASWJ terrorists? https://lubpak.com/archives/306125

Commet by Engineer Ali Abbas

via facebook:

While Bacha Khan was in India , once in his last ages for treatment , a time came when Indian Doctors were expecting him to die any time. During that period a Helipad was prepared as a special case at Maddrasah Deband for his Namaz E Janaza. Though he recovered and came back .. and died little latter … his love for Deobandi School of thought was not hidden from any body

A historical reserach on South Asian fanatics, Pashtuns and Deobandism https://lubpak.com/archives/325051