Editorial: What is Pashtun nationalism?

Related posts: Why are Pashtun nationalists mute on Deobandi ideology and identity of TTP-ASWJ terrorists? – See more at: https://lubpak.com/archives/306125

Role of Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the spread of Deobandi ideology in Pashtuns – See more at: https://lubpak.com/archives/306211

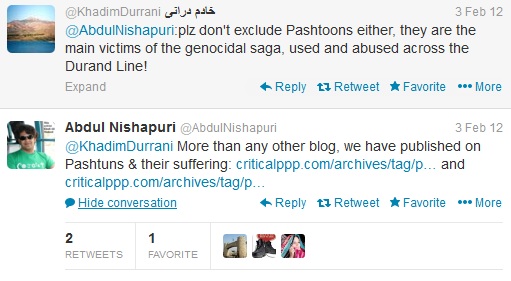

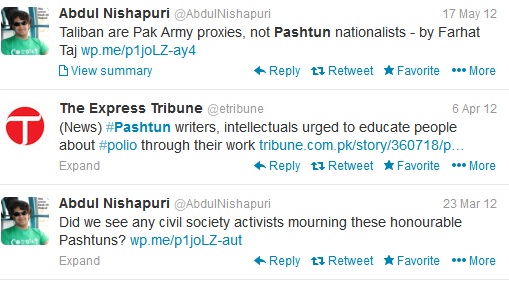

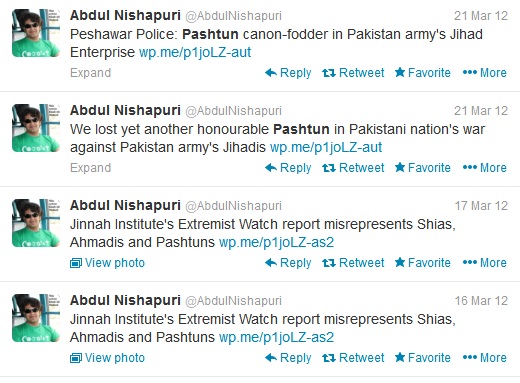

Abdul Nishapuri, the founder-editor of this blog, in a tweet asked, “Many, not all, of those who are protesting Pakistan army’s ‘massacre of Pashtuns’ in Waziristan were dead silent on Pashtuns of Parachinar!”

His question did not ruffle any feathers. No Pashtun nationalist or intellectual took it up. Why? The answer was provided by Abdul Nishapuri himself when no one else came forward: “The people of Parachinar aren’t given the status of full Pashtuns as they’re Shias”. Again, no one responded to Mr Nishapuri. No Pashtun refuted his claim by saying that Pashtun Shias are as much Pashtun as Pashtuns of any other persuasion.

Pashtun nationalism is one of the great myths created by both the Pashtun and the non-Pashtun. What is meant by Pashtun nationalism? The answer given all the time is: A Pashtun is a Pashtun as long as he (note: ‘she’ is always absent in this discussion) speaks Pashto. Apparently this is a broad definition. It certainly does not include the biological side of Pashtun ethnicity, if not race. But ethnicity is a problematic issue. There are a number of Syeds/Shahs and Awans who identify themselves as Pashtun and have been in the vanguard of the Pashtun nationalist posturings. Then there is the issue of Khattak versus Khan. Many Khans will unhappily react if called “Khattak”. Thus, language is more potent a symbol than ethnicity when it comes to the Pashtun identity.

But still the issue of Pashtun nationalism remains problematic, and this editorial in no way claims to be able to straighten it out. Being an editorial, it is more of a viewpoint open to falsification than a piece of conclusive research. But hopefully, it can make a few relevant points. We want to begin with the question: What lies at the foundation of nationalism? In other words, where does nationalism come from?

If we consider views of credible theorists of nationalism, we find interesting points. Anthony Smith claims that nationalism is a result of a group’s reaction to modernity. Ernest Gellner stakes his claim on industrialisation. Benedict Anderson argues that it is capitalism and the print media which are at the basis of nationalism. But if we take a look at Bacha Khan’s Pashtun-nationalist movement in the 1930s, we find that all these factors were missing in the Pashtun society of that time. Even to this day, only a city like Peshawar can claim to have some of these factors in operation. The rest of the KPK is more or less a continuation of the past.

There is another view widely subscribed by Pashtun and non-Pashtun researchers that despite Bacha Khan’s movement, the roots of Pashtun nationalism goes back Khushal Khan Khattak (1613–1689). It was against the anti-Pashtun policies of the Emperor Aurengzeb that Khushal Khan Khattak (both Khan and Khattak!) raised a voice in order to unify the Pashtun.

From the brief discussion above, two points emerge. First, the frameworks of the theorists of nationalism are inadequate, and we need a new framework to understand Pashtun nationalism. Second, what is claimed to be Pashtun nationalism is not nationalism but something else. One fact which supports the latter view is that Pashtun nationalism, if there is such a thing, has no territorial claims. In the past, Bacha Khan raised voice for Pashtunistan, but now his own party, the ANP, headed by his grandson subscribes to nothing of this sort. It must be noted here with some emphasis that Bacha Khan was not a nationalist. A nationalist looks ahead. But Bacha Khan was merely an idealist who looked back at the past and regretted its loss. Whatever he thought about the Pashtun of his time, it was done in nostalgic terms. Here is a sample of his ‘nationalistic’ views,

Food used to be simple and because of that people’s health was good, they were not as weak as they are today. There were no spices, no tea. Usury, alcohol and sex without wedlock were considered very bad and if anyone was suspected of indulging in these things he would be ostracised… there was no moral bankruptcy like in today’s world. A guest would be treated to a greasy chicken curry… as far as food was concerned there was no difference in the rich and the poor. The rich and the poor used to dine together. Just like dress and food, houses were simple, too. The huge and comfortable houses of today did not exist, but still the kind of happiness and content that was there in people’s life does not exist today. There were no diseases; men and women had good and strong bodies. Grown up girls and boys would play together till late in the night. They would look at each other as brothers and sisters. Moral standards were very high.

(Excerpted from Bacha Khan’s book My Life and Struggle)

This is the same Bacha Khan who refused to have anything to do with his fellow Pashtun in Afghanistan calling them “those naked people!”

While Bacha Khan must be credited for some things such as emphasizing women’s education and the mobilization of the Khudai Khitmatgar movement, he should not be above criticism. Furthermore, the criticism of Bacha Khan by the Pakistani establishment is both shallow and baseless – that in itself does not mean that valid criticism of his work and activism cannot be made.

Thus it appears that there is no such thing as Pashtun nationalism. Had it been so, the Shias of Parachinar would have been defended by their fellow Pashtuns. But it is at the hands of the Pashtun Taliban that the genocide of the Pashtun-Shias of Parachinar has been going on for over two decades, but not a single Pashtun nationalist voice has been raised against it. No vigils are kept for these Shias. But when the Pakistan Army announces action in North Waziristan, all Pashtun voices—be they leftist ANP, far right JUP, or liberal public and journalistic views—are raised against it calling it ethnic cleansing of the Pashtun.

When people talk about Pashtun nationalism, they are mistaken or do so deliberately. It is indeed the Pashtun worldview which is religious, messianic, and binary. Historically, it is on this principle that the Pashtun have dealt with people and situations. “A Pashtun is a Muslim by definition,” goes the saying. But it is a certain kind of Muslim. It is a crusader-messianic Muslim. Educated Pashtun claim that Ahmad Shah Durrani was the highest point in the annals of Pashtun nationalism. He was notorious for killing Shias. The likes of Tariq Ali claim that the Taliban are anti-imperialist Pashtun nationalists. The Taliban’s recoded of Shia killing is an ignoble as any. The Pashtun Kings of Afghanistan killed the Hazaras in the past not for their ethnicity, but for being Shia. Last, it was the poet Ghani Khan, a son of Bacha Khan, who made an important observation. In his The Pashtuns, he discusses the Pashtun mindset. He regards the Shia Pashtuns as highly intellectual and sophisticated, and notes that they have been a repeated target of Sunni-Pashtun jealousy and anger.

Thus the silence of the Pashtun over the genocide of the Shia-Pashtun of Parachinar has nothing to do with the so-called Pashtun nationalism. It is a result of the Pashtun Manichaean worldview in which the world is divided into good and evil. The likes of Abdul Nishapuri will find no interlocutor.

LUBP Archive About Pashtuns :

https://lubpak.com/archives/tag/pashtuns

I think the Author is confused and has zero knowledge about Pashtuns , as Pashtun Nationalism has no relationship with Islam or sects like Shia and Sunni , and Pashtuns are Pashtun even if Muslims or Non Muslims like Kapoors Hindus or Jewish Pahtun setlers in Israel from Afghanistan Pakistan or Indian area in mid 1940,s ,

why AnP does not say something is very simple in expalnation that is Fata is not domain of Pakhtunkhwa home of ANP where politics are allowed by Punjabi and Muhajir dominated Paki estabalishment since quaid I azam but in FATA according to Article 247 Fata is not a democraric area it is controlled directly by Islamabad Fata secretariate , under president direct control and Islamabad Burecrats who’s rep is political Agent who is more powerful then CM Pakhtunkhwa or governor even or 8 Fata senators or 21 MNA who are not allowed to make laws for Fata as they can’t vote for it even after 18 amendment .

second factor is Fata people work through jirga system of self rule and they are not under law of Pakistan like supreame court or Peshawar high court accoeding to article 247 of Paki constitutions , so ANP or any party is practically helpless and can’t raise any voice for it , as it would amount to breaking the law of Pakistan .

ANP furthermore never has opposed war on Taliban another lies and false hood of your article and distorting the facts , Bacha khan always opposed mujahideen / Taliban which is on record as they are same bullshit and changing name from mujhahideen to Taliban does not make matters changed , a totally biased and in accurate article as ANP has been raising voice countless time for kurrum people on talk shows and party gatherings rallies and press confererences , rather it is pti ,MMA and pml that is more of wahabi / deobandi and anti Shia in nature please correct your article it simply missinformed to level of jihalat .

AnP lately in last elections was not allowed to have not a single rally by friends of Author the Taliban and even corner meetings were attacked and they lost 2000+ workers and leader more than Paki army so targeting them is a bit unjustified and shows bias and jihalat to facts .

ANP recently protested in the parliament about the alleged massacres of (Deobandi) pashtuns by Pakistan army in waziristsn. No such reaction to the decade long siege and massacre of Shia pashtuns of parachina r by pasting talibs backedby punjabi generals.

it is strange people are soundung unreason able that instead blaming 22 mna of Fata and 8 Fata senators and the pmln government of nawaz Sharif that is in charge of Fata they are unreasonably asking for a protest from AnP who have never ruled Fata or will ever do as they are in different province called Pakhtunkhwa in opposition with 4 mpa only , while I might remind the author the current govt of Pakhtunkhwa is of PTI with 40 mpas and that of MMA , why you don’t ask for their protest , it is absurd situation to ask from protest from some one whom one does not vote .

As my Bangash friend from Hangu used to say, “Kisi qom may shia k khilaf itna bughz nahi jitna pashtono may hai, Taliban humay maartay hain or wahan k log unko panah detay hain, pehlay yehi log humaray sath chai peetay thay” at that time Shia killing was not very high in Pakistan but only in Parachinaar and Hangu.

Ahmad Shah Abdali was a General in Army of Shia Nadir shah of Iran and he was raised as his son to correct the false hood the Author is Projecting , with out any credible research and information .

Nadir shah Rangela as he was called was a shia and he came from Iran and attacked Delhi and left the Qazilibash shias to rule Delhi , and he was killed by his own wife and he had in his life Recommended that Ahmad shah Abdali Pashtun his General made King after his death and hence the New king of India was Ahmad shah abdali Pashtun started Abdali / Durrani Empire from 1757-1857 on India and half of it survived till 1980 in Afghanistan till it was Finished in 1980 by Taliban Deobandi Agents of Muhajir and Punjabi Dominated Army of Pakistani Establishment

Pakistani Establishment is following the theories of Deoband ( Indian ) from India and Raiwind Markaz in Takht i Lahore , and theories of Muhajir Maulana Mududi and Qasim Naintwai and Obaid Ullah Sindh a Punjabi Sikh from Sialkot ( British Employees of East india company as teachers) , and these school of thoughts were adopted by a Muhajir Gen ZIa ul haq and another Muhajir General Yahya Khan Qazilbash shia a Muhajir who made Jamaat Islami and JUI with ISI help for the record , and then Gene real Aslam beg another Muhajir and General Musharraf are all responsible for Shia Massacres as they are the ones who created Lashkar Jhangavi and Sipah Sahaba , I ask a Question from Author , is Maulana Tariq Jamil , Mullah Fazullah head of HUJI Taliban and all Sipah Sahaba heads like Ludhinavi arent they all Muhajirs and Punjabi who head the Theological wings of Taliban spewing hate against Shias, as Kafirs and those who are Butchering the Shia,s , so why doesn’t he point the Gun to these Muhajirs and Punjabi’s who are fathers of Taliban and why he is attacking just Pashtun Nationalist .

Why he Forget the it was father of Malalaa Mr zia Uddin who was head of Pashtun Student federation in Jehnzeb college swat is from ANP , he sacrificed all his 8 schools his life and his daughter to Fight the Taliban , one has to be Blind and mentally Imbecile and retarded not to see the contribution of ANP as she is one who was nominated form Noble Prize , got Awards equal to Nelson Mandela and Biggest European awars and she was shot Fatlly in her head for opposing Taliban and author still says there is no civil society of Pashtun .

Malalaa has mentioned Kurrum People in her book ” I am Malalaa ” and yet the finger are not pointed to ANp and not to fore fathers of the Author and his clan who are actual fathers of Taliban and not a Single Pashtun is found in one who made Taliban or Sipah Sahaba or Lashkar Jhangavi .

I words of Nelson Mandella ” My Favorite was Bacha khan and i copied his style ” in Freedom Struggle of South Africa , taken from his Memoirs of Nelson Mandela .

Bacha Khan spent 35 Years in Prision of British and Punjabi Establishment and it is so painful that people still has no Idea what an Icon he is .

Pashtun Race was created by Male side genes from Chengiz Khan and Halakoo Khan’s and other Khans from Tataars and Mangols and Aryan women of Afghanistan. Strong combination but the annual killing instinct still remained in Pashtuns which finds many reasons to kill. Tribal battles, inside home killings for honor were everyday stories in all Pashtun homes. Then British and American utilized the killing natures of Pashtuns to create Talibans and now those remaining Talibans have been sent to Iraq and Syria to support Al Qaeda and formed ISIS there.

The Simple Methods To Understand watch And Also The Way One Can Be a part of The watch Top dogs

Fed up with the numerous men announcements? We are at this website to suit your needs!

agree to my apology due to miscalculation the best link is definitely:

louis vuitton outlet http://chefdrivendc.com

Points have altered. Not really all people are able to buy practical stuffs any more.. . -= Rockstar Sid’s last website… The 3 Specific Investments Which often Have to Make the most of ipad device =-.

louis vuitton outlet http://godhopmovement.com

Decorative mirrors is just as its name implies, is for the ladies do street, tie-in dress have equipped with act the role of article, lens general with light color series maintenance, generally for pale pink, this type of glasses easier collocation summer clothing. Sales, said sales member special use mirror also called polarize, mainly for the beach, mountaineering wait for outdoor activities.

A historical reserach on South Asian fanatics, Pashtuns and Deobandism https://lubpak.com/archives/325051