Masood Azhar: The man who brought jihad to Britain

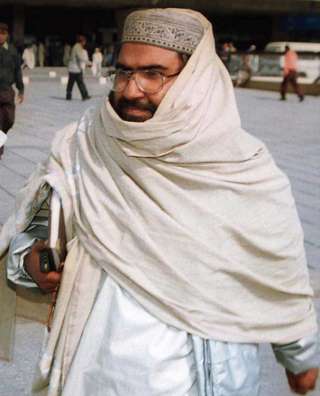

Masood Azhar, today the head of one of Pakistan’s most violent militant groups, was once the VIP guest of Britain’s leading Islamic scholars. Why, asks Innes Bowen.

When one of the world’s most important jihadist leaders landed at Heathrow airport on 6 August 1993, a group of Islamic scholars from Britain’s largest mosque network was there to welcome him.

Within a few hours of his arrival he was giving the Friday sermon at Madina Mosque in Clapton, east London. His speech on the duty of jihad apparently moved some of the congregation to tears. Next stop – according to a report of the jihadist leader’s own magazine – was a reception with a group of Islamic scholars where there was a long discussion on “jihad, its need, training and other related issues”.

The visiting preacher was Masood Azhar. Today he is wanted by the Indian authorities following an attack on the Pathankot military base in January this year. In 1993 he was chief organiser of the Pakistani jihadist group Harkat ul Mujahideen.

A BBC investigation has uncovered the details of his tour in an archive of militant group magazines published in Urdu. The contents provide an astounding insight into the way in which hardcore jihadist ideology was promoted in some mainstream UK mosques in the early 1990s – and involved some of Britain’s most senior Islamic scholars. Azhar’s tour lasted a month and consisted of over 40 speeches.

The Deobandis will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 09:00 BST on Tuesday 5 April and Tuesday 12 April.

According to an account of the visit, after a series of speeches at east London mosques, Azhar headed north. Zakariya Mosque in Dewsbury, Madina Masjid in Batley, Jamia Masjid in Blackburn and Jamia Masjid in Burnley were among the venues for his jihadi sermons in his first 10 days in Britain. Such was Azhar’s popularity in those northern towns that wherever he went, pied-piper like, he accumulated more scholars as part of his entourage.

The most surprising engagement of the tour was the speech Azhar gave at what is arguably Britain’s most important Islamic institution – a boarding school and seminary in Lancashire known as Darul Uloom Bury. It is also home to Britain’s most important Islamic scholar, Sheikh Yusuf Motala.

According to the report of the trip, Azhar addressed the students and teachers, telling them that a substantial proportion of the Koran had been devoted to “killing for the sake of Allah” and that a substantial volume of sayings of the Prophet Muhammad were on the issue of jihad.

By the time Azhar arrived at Darul Uloom Bury there could have been little doubt about his agenda. A few days earlier several scholars from the seminary had attended the inauguration ceremony for the Jamia Islamia mosque in Plaistow where Azhar spoke on “the divine promise of victory to those engaged in jihad”.

A series of recordings from the trip, uncovered by the BBC, gives a flavour of the message at some of the venues. “The youth should prepare for jihad without any delay. They should get jihadist training from wherever they can. We are also ready to offer our services,” Azhar told one audience in a speech entitled “From jihad to jannat [paradise]”.

The story of Masood Azhar’s trip to Britain does not fit the narrative promoted by Muslim community leaders and security experts alike. According to them, the spread of jihadist ideology in Britain had nothing to do with the UK’s mainly South Asian mosques. The source of all the trouble, they say, was a bunch of Arab Islamist exiles – the likes of Abu Hamza and Omar Bakri Mohammad.

These Wahhabi preachers, who operated on the fringes of Muslim communities, certainly played an important role in radicalising elements of Britain’s Muslim youth. But it was Azhar, a Pakistani cleric, who was the first to spread the seeds of modern jihadist militancy in Britain – and it was through South Asian mosques belonging to the Deobandi movement that he did it.

The Deobandis control more than 40% of British mosques and provide most of the UK-based training of Islamic scholars. They trace their roots back to a Sunni Islamic seminary founded in Deoband in 19th Century India. Today it is a diverse movement – the original seminary in India has issued a fatwa against terrorism – but some Deobandi madrassas in Pakistan have propagated jihadist ideology.

Among the congregations of many of Britain’s Deobandi mosques, the fact of Masood Azhar’s 1993 fundraising and recruitment tour is something of an open secret. But talking publicly about such events is not the Deobandi done thing. So to the wider world, the details have remained a mystery – until now.

Azhar was 25 years old when he was given the red carpet treatment by some of Britain’s Deobandis. His cause was the disputed territory of Kashmir. Azhar and other mujahideen leaders recast what had been a Pakistani-Indian nationalist struggle into a jihad of Muslims versus Hindus. In 1993, al-Qaeda was yet to declare war on the citizens of the United States and its allies, but after it did, Azhar’s group became an affiliate.

The consequences of the British Deobandi link with Masood Azhar became more obvious in December 1999. An Indian Airlines plane was hijacked and grounded at Kandahar in Afghanistan. The passengers were held hostage pending the release from an Indian prison of Masood Azhar and two of his jihadist associates – one of whom was a 26-year-old student from London, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh.

Saeed had been jailed for kidnapping Western hostages in India. After the three men were released, Azhar founded his own militant group, Jaish-e-Mohammed. Saeed went on to be involved in the 2002 kidnap and killing of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in Pakistan.

One of the first recruits to Azhar’s new militant group was Mohammed Bilal from Birmingham. Bilal blew himself up outside an army barracks in Srinagar, killing six soldiers and three students in December 2000.

But there was another serious consequence of the Masood Azhar connection – the training camp facilities and logistical support he provided to British Muslims willing to carry out attacks in the UK. Several UK-based plots including 7/7, 21/7 and the attempt in 2006 to smuggle liquid bomb-making substances on to transatlantic airlines are now thought to have been directed by Rashid Rauf, a man from Birmingham who married into Masood Azhar’s family in Pakistan.

The views of Britain’s Deobandi congregations towards Masood Azhar after his alliance with al-Qaeda are not revealed in the archive of jihadist publications seen by the BBC. Did British support for him evaporate or just go underground?

One man with a rare combination of inside knowledge and a willingness to talk is Aimen Dean, a former member of al-Qaeda. He was recruited by Britain’s intelligence services in 1998 after he started to have doubts about Osama Bin Laden’s agenda. Dean maintained his links with al-Qaeda in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan while working undercover for MI5 in Britain for eight years.

“Pre-9/11, there was no question that the Deobandis supported the Taliban of Afghanistan to the hilt,” he says. The Taliban, like Azhar, regard themselves as Deobandis.

Aimen Dean preached in many Deobandi mosques in the UK. “Even after 9/11, there were many mosques still stubborn in their support for the Taliban,” says Dean, “because of the Deobandi solidarity.” Dean did not make open calls to jihad from the pulpit. He would instead give a talk on an innocuous topic such as Islamic history. Through his speaking engagements Dean came into contact with jihadist sympathisers who would invite him to gatherings in private homes.

Aimen Dean is a founder member of al-Qaeda, who changed tack in 1998 and became a spy for Britain’s security and intelligence services, MI5 and MI6. Interviewed by Peter Marshall, he describes his years working in Afghanistan and London as one of the West’s most valuable assets in the fight against militant Islam.

Among the top ranking Deobandis in Britain, one name appears in the publications of several different militant groups.

The jihadist archive reveals that Manchester-based scholar, Dr Khalid Mehmood’s connections with Azhar pre-dated the 1993 UK tour. At the 1991 gathering in Pakistan of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, Mehmood was among the speakers. He says he was there to discuss theological issues and in no way condoned acts of terrorism and violence.

As with other British Deobandi scholars, references to Mehmood disappeared from the pages of Azhar’s magazines well before 9/11. However his name appears in the magazine of Sipah-e-Sahaba, a militant group responsible for killing Shia Muslims and other religious minorities in Pakistan.

According to one report, when Sipah-e-Sahaba’s leader Azam Tariq visited the UK in 1995, Mehmood spoke at the same events as him on a tour of Scotland. Mehmood says that he did not attend these events in their entirety and therefore could not know what was said by other speakers including Azam Tariq.

The preface to the first volume of a pro-Sipah e Sahaba history, published in 2000, is attributed to Dr Mehmood. He says that his name has been used falsely. Despite the fact that Sipah-e-Sahaba was banned in the UK in 2001, Mehmood addressed a conference in South Africa in December 2013 at which the head of Sipah-e-Sahaba, Muhammad Ahmad Ludhianvi, also spoke. Mehmood says he has always been involved with a public exchange of ideas which inevitably means sharing a platform with those with whom one disagrees.

Mehmood’s name appears in the publications and conference programmes of Aalami Majlise Tahaffuze Khatme Nubuwwat (AMTKN), a sectarian group that campaigns against Islam’s minority Ahmadi sect. The literature published on the Pakistani website of AMTKN states that Ahmadis who refuse to convert to mainstream Sunni Islam are wajib al-qatl, which means deserving to die. AMTKN is a legal organisation in the UK, registered with the Charity Commission.

There appear to be connections between Masood Azhar, Sipah-e-Sahaba and AMTKN. The late leader of Sipah-e-Sahaba, Azam Tariq, was a close associate of Azhar. Furthermore some of those mentioned in the publications of Sipah-e-Sahaba also appear to have been associated with AMTKN. A senior Deobandi scholar based in Saudi Arabia, Abdul Hafiz Makki, appears in the records of all three movements.

Britain’s most important Islamic scholar, Sheikh Yusuf Motala was, according to the groups’ own publications, involved in both the forerunner to AMTKN and in Sipah-e-Sahaba before it was banned.

What though does Sheikh Yusuf Motala now make of these groups and of Masood Azhar’s jihadist message? In a handwritten note in Urdu, he said he had always hated such activities and had published his thoughts on the matter in a book. “During the last several decades, I have neither uttered Masood Azhar’s name in my speeches, even by mistake, nor mentioned his group, nor talked about any nihilistic terrorist action.”

Indeed the ethos at his seminary in Bury appears to be far removed from the jihadist sermons of Azhar. An unannounced Ofsted inspection in January 2016 found that pupils had a deep understanding of “fundamental British values, such as democracy, rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance for those of different faiths”.

It is a moderate approach which is in evidence elsewhere in Deobandi circles. At a fundraiser in London for a new Islamic seminary, a popular young preacher educated at Bury spoke respectfully of other faiths. A part-time academy for children run by young Deobandi graduates in London makes a point of adopting a non-sectarian approach and attracts non-Muslim children.

But the influence of Pakistan’s far right, religio-political movements is still deeply embedded in large parts of the Deobandi network in Britain. There are many moderates among the faithful but they often have little institutional power. The struggle to gain influence seems to be particularly difficult outside London.

When the BBC recently revealed that a senior member of the management committee of Glasgow Central Mosque had been an office bearer in Sipah-e-Sahaba, he was not required by the mosque management to resign.

One member of the Glasgow Central Mosque told us that, appalled as he was by these revelations, he was worried that speaking publicly would put him and his family in danger. His fears were prompted by the resignations due to intimidation of a new, moderate management committee elected by the congregation.

In the Midlands, one practising Deobandi Muslim told me he had been threatened with excommunication and violence for raising concerns about, among other issues, the propagation of sectarian hatred. A niqab-wearing Deobandi woman told a similar story about her attempts to encourage more positive attitudes to other faiths.

These religious conservatives, being visibly Muslim, face prejudice from a non-Muslim population concerned about terrorists. But they pay a price for opposing the extremism in their midst. In all three cases the word “mafia” was used to describe those who had sought to intimidate them.

“Everyone who is working for a just, decent society should contribute in any way they can to tackle these issues,” says one, “It might have been politically incorrect to take on the mosques but these things should be exposed.”

Source:

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35959202?SThisFB

Appendix

Renowned Pakistani journalist Khaled Ahmed describes HuJI, HuM, JeM and other HuA all chips of the same bloc because of their origins from the same Jamia Uloom-ul-Islamia, Banori Town seminary (madrasah), Karachi. The seminary was established in 1954 for the purpose of proselytizing and educate masses and to promote Deobandi sect of Islam[7]. The same seminary was active in mobilizing support for Afghan mujahedeen during Afghan War (1979-89) and later for Kashmir insurgency, and finally its cleric had gone to every extent to support Taliban regime (1996-2001) in Afghanistan[8].

Even though it is located in Karachi, Sindh province in southern Pakistan, the majority of its faculty members and students are from Khyber-Pakhtunkhawa province. The seminary is a Pashtun enclave in downtown Karachi as it draws most of its student body from northern Pashtun areas of Pakistan. The seminary was founded by Maulana Yousaf Banuri, an ethnic Pashtun hailing from Buner district of Khyber province. In later years, key figures such as Yousaf Ludhyanvi and Rashid Ahmad played pivotal roles in promoting Deobandism in Pakistan. But it was Maulana Nizam udidn Shamzi, another Pashtun, who indeed made open the pro-Taliban, anti-American, anti-western, and anti-Shia agendas. [9]

More radical dangerous than his predecessors, Shamzai cultivated relations with Bin Laden and other Arabs stationed in Afghanistan. Khaled Ahmed and John C Cooley both write about these relations in their books as “The most well known head of the Banuri complex was Mufti Nizamuddin Shamzai (1952-2004) who was counted as the most powerful man in Pakistan during the rule of Mullah Umar in Afghanistan. John C Cooley writes that Osama Bin Laden used Shamzai’s Banuri Town seminary as his base in Karachi for some time. Shamzai, together with Samiul Haq of Akora Khatak, was greatly revered by the Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Umar. Among his 2000 fatwas, the most well known was the one he gave against America in October 2001, declaring jihad after the Americans decided to attack Afghanistan. He had earlier in 1999 already deemed it within the rights of the Muslims to kill Americans on sight.” [10]

http://www.cf2r.org/…/a-profile-of-harkat-ul-mujahedeen…

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35959202?SThisFB