ایل یو بی پی کے بارے میں جناب علی ارقم کا ناروا پراپیگنڈہ – از عامر حسینی

میں جب بهی دیوبندی تکفیریوں کےساتھ دیوبندی مکتبہ فکر کے انتہائی اہم ترین مدارس کے انتہائی جید اور فاضل علماء کے تعلقات اور سرپرستی کے بارے میں لکهتا ہوں تو میرے بہت سے کرم فرما جن میں خود کئی پختون قوم پرست دانشور اور پختون ترقی پسند بهی شامل ہیں وہ ناراض ہوجاتے ہیں اور کالعدم دہشت گرد جماعت سپاہ صحابہ (نام نہاد اہلسنت والجماعت) اور طالبان وغیرہ کے ساته لفظ دیوبندی لگانے پر سیخ پا ہوتے ہیں مجهے فرقہ پرستی کا طعنہ بهی سننے کو ملتا ہے

زرا اس تصویر کودیکھ لیں یہ مولانا عبدالرزاق سکندر کے ساته محمد احمد لدهیانوی کے ساته تصویر ہے اور وکی لیکس کی اس رپورٹ کو بهی پڑھ لیں جو دیوبندی مولویوں احمد لدهیانوی اور فضل الرحمان کو عرب ملکوں سے امداد ملنے کی تصدیق کرتی ہے

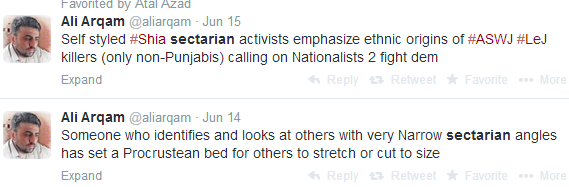

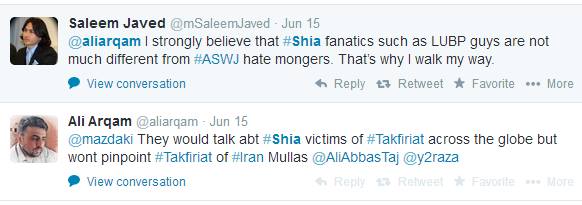

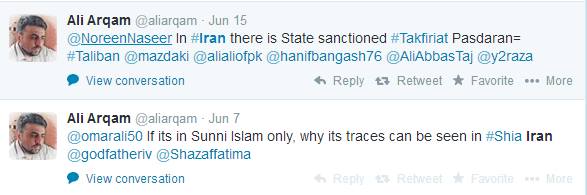

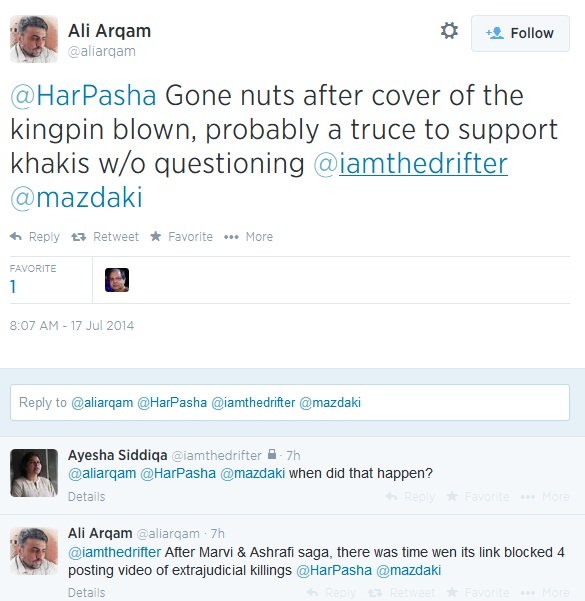

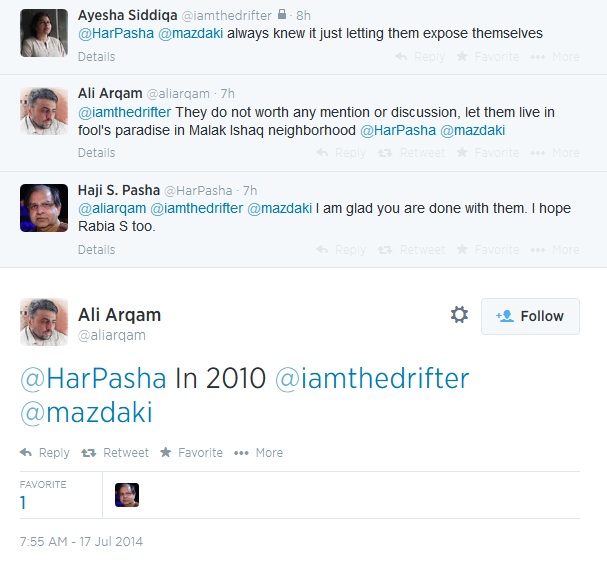

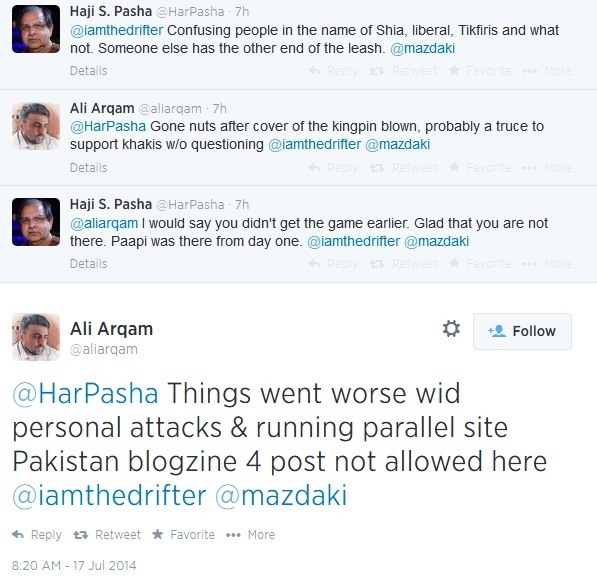

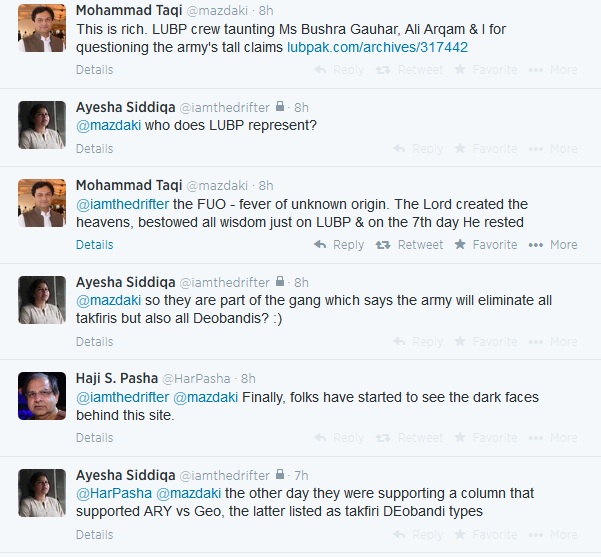

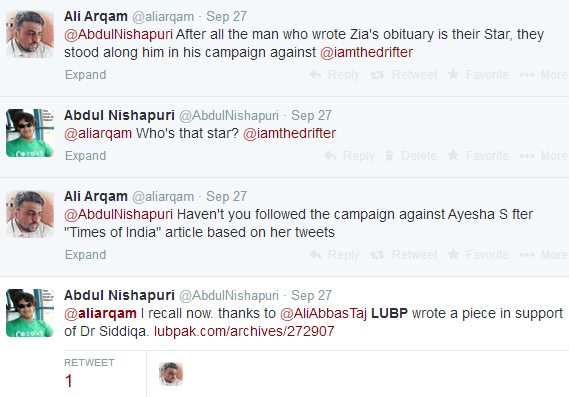

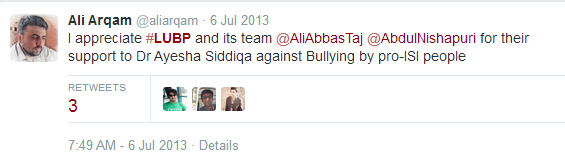

ابهی کچه دن ہوئے جب علی ارقم نے جوکہ پشتون ترقی پسند لکهاری ہیں ٹوئٹر پر ہونے والی ایک مباحثاتی نشست میں جس طرح سے عائشہ صدیقہ کو تعمیر پاکستان ویب سائٹ کے بارے میں گمراہ کرنے کی کوشش کی اس کا مجهے کافی افسوس ہے اور علی ارقم نے یہ سب اس لئے کیاکہ ایل یو بی پی کی جانب سے باقاعدہ تحقیق کے ساته دو نکات تواتر سے پیش کئے گئے – ایک تو یہ کہ پاکستان میں بالخصوص اور برصغیر پاک وهند میں بالعموم جو مذهبی دہشت گرد تنظیمیں سرگرم ہیں اور شیعہ، صوفی سنی، مسیحی ،احمدی، سیکولر لبرل پر جو حملے ہورہے ہیں ان میں ملوث افراد کا تعلق دیوبندی فرقے سے ہے اور دوسرا نکتہ یہ ہے کہ دیوبند تحریک کے اندر آغاز سے ہی ایسی لہریں موجود رہی ہیں جو اس مکتبہ فکر کے نام نہاد جہادیوں کو دیگر مسلمانوں اور معصوم غیر مسلم برادریوں کے خلاف لڑائی اور دہشت گردی پر کمربستہ رہی ہیں

پهر تعمیر پاکستان ویب سائٹ کی جانب سے دیوبندی دہشت گردتنظیموں کے ممبران اور لیڈر شپ کی کثیرالنسلی دیوبندی شناخت پر بهی اصرار کیا گیا اور اس کو استدلال و شواہد کے ساته پیش کیا جاتا رہا

تعمیر پاکستان کا یہ موقف بالکل جائز ہے کہ اے ایس ڈبلیو جے، ٹی ٹی پی سمیت جتنی بهی دہشت گرد جماعتیں ہیں وہ دیوبندی جماعتیں لیکن ہر دیوبندی دہشت گرد نہیں ہے مگر دیوبندی علماء اور سیاسی مذهبی جماعتیں دیوبندی دہشت گرد تنظیمیوں کے خلاف نہ تو کهل کر کوئی فتوی دیتے ہیں اور نہ ہی ان سے خود کو الگ کرتے ہیں

میں اس موقف کو بالکل ٹهیک خیال کرتا ہوں اور صاف صاف کہتا ہوں کہ علی ارقم نے ظلم عظیم کیا ہے جب اس نے ڈاکٹر عائشہ صدیقہ اور بعض اور لوگوں کو یہ کہ کر گمراہ کرنے کی کوشش کی کہ ایل یو بی پی ہر دیوبندی کو دہشت گرد خیال کرتا ہے اور یہ سمجهتا ہے کہ وہ پاک فوج کے زریعے سے سب دیوبندیوں یا سب پشتونوں کو صفحہ ہستی سے مٹادے گا علی ارقم نے یہ ایک انتہائی ناروا اقدام کیا ہے جس پر مجهے انتہائی دکھ ہے

میں ڈاکٹر عائشہ صدیقہ سے کہتا ہوں کہ انہوں نے علی ارقم اور چند اور لوگوں کی گمراہ کن باتوں سے جو اندازے ایل یو بی پی کے بارے میں قائم کئے وہ درست نہ ہیں

میں بهی مذهبی دہشت گردی کو پختون، پنجابی، بلوچ یا کسی اور نسل یا قوم کے ساته خاص کرنے کا مخالف ہوں لیکن یہ درست ہے کہ پاکستان میں عصر حاضر کا تکفیری و خارجی فتنہ دیوبندی مکتبہ فکر کے مدارس سے اٹها ہے اور جو بهی اسے سنی شدت پسندی یا سنی دہشت گردی کہتا ہے یا اسے پنجابی یا پختون فنومنا بتلاتا ہے وہ یا تو سخت غلط فہمی کا شکار ہے یا شعوری طور پر علمی بدیانتی اور نسلی تعصب میں مبتلا ہے

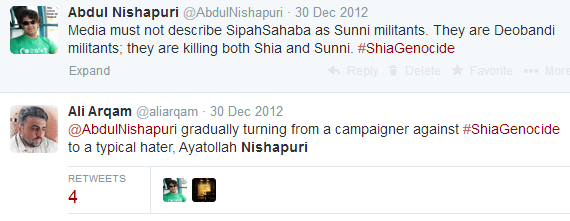

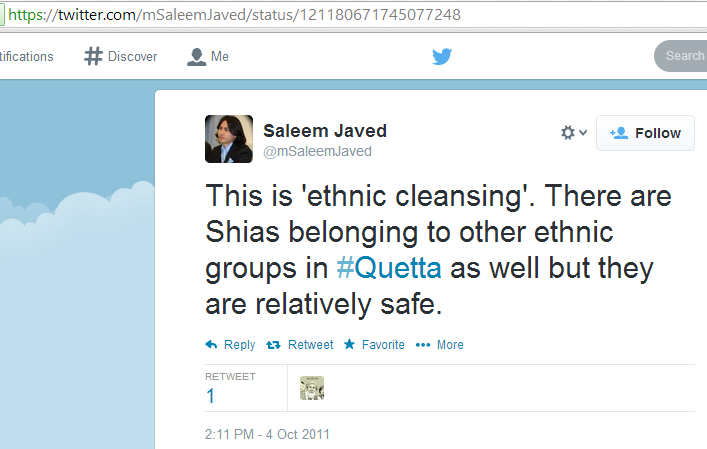

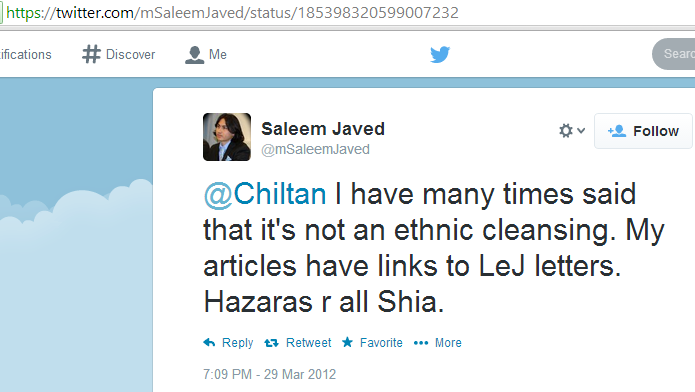

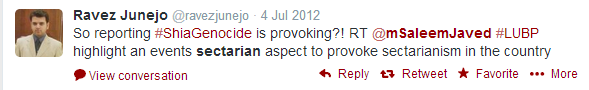

اب ذرا ایک سال قبل کی ٹویٹس کا بھی جائزہ لے لیں

DAWN – Opinion; October 05, 2007

Published Oct 05, 2007 12:00am

Comment Email Print

Whose game is it?

By Ayesha Siddiqa

SEPTEMBER 29 has been marked as another dark day in Pakistan’s history. It was a day when the state’s coercion was used against innocent journalists and lawyers. The authorities felt the need to use brutal methods to control the people. Interestingly, it was also the first time in history that the police resorted to the ways of street urchins and pelted the protestors with stones.

It seems that it is not only the general public that has learnt something from the Palestinian Intifada. Such tactics were used to physically assault people like lawyers Aitzaz Ahsan and Ali Ahmed Kurd.

Apparently, the khakis are extremely unhappy with the Chief Justice’s team of lawyers and are determined to sort these people out for challenging the army chief and making comments denigrating his uniform. The regime has shown its ugly face which had been feared eight years ago when Pervez Musharraf seized power. This may not be because he is a born tyrant but due to the nature of his personal and organisational power.

Since the military lacks political legitimacy, it is bound to end up in conflict with society within a few years of taking control. The dictator starts out with good intentions but soon runs into problems created due to his utter lack of understanding of politics.

The military dictator is accustomed to another culture which is more organised and disciplined. Such a culture looks good in a bureaucracy but not in politics where different stakeholders vie for a greater share of political, financial and other resources. So, the dictator soon gets out of breath and embarks on the path of coercion. The more time he spends at the helm, the more frustrated he becomes. The more frustrated he gets the more coercive his regime is. This cycle is unchangeable when the military comes into power.

To those who believe that General Musharraf is an extraordinary man who can rise above this cyclic behaviour, one would like to pose this question: who gave orders for the brutality that was on display on May 12 and Sept 29?

Logically, (if we forget for a minute that this is not another military regime) the government should not have shown aggression soon after the Supreme Court judgment even if it wanted to send a message to the general public that any difference of opinion and act of disobedience would not be tolerated. Although pressure from several sides was mounting, Musharraf had won a round of the political battle when the Supreme Court rejected the petitions challenging his eligibility for the presidential race.

Was it Musharraf himself who ordered the police to use the tactics of street urchins? Perhaps not. He is certainly not choreographing the entire show of his regime. In fact, possibly the problem exists that he is not in total control of all parts of his government including the armed forces.

Some might consider this an extreme conclusion and would argue that he is very much in control. In this case, it is nothing more than poor intelligence which the agencies are quite capable of. Historically, the intelligence agencies have never been up to the mark in informing a regime intelligently.

In 1965, these agencies had advised the government that Kashmiris in Indian-occupied Kashmir were ready for a revolt against the Indian forces, which they were not. During the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s, these very agencies had given poor advice to the government about the reaction of the Bengali population in East Pakistan. Very recently, the agencies were found to have no information (or pretended not to have any) on the Lal Masjid crisis in the heart of the capital.

It was also a dire miscalculation on their part that the lawyers’ movement would die down within a couple of months, which it didn’t. One could go on and on about the failure of the intelligence in this blessed country.

But then, why is no one checking such failures — or is it really a question of how much General Musharraf is in control of the situation? A political crisis is a good way for the organisation to get rid of an individual when he refuses to give up. Surely, people around the top general know how greater coercion is counterproductive. More aggression will create the opposite result of what the regime would like to see.

Domestic politics, however, is not the only area where policy contradictions are obvious. One equally draws a blank in understanding the policy on militancy. Are we trying our best to eliminate the militants? Have all connections in the name of a higher strategic mission been ruptured? Or is there still a tactical linkage with some militant organisations?

It is not just that foreign agencies and think-tanks point an accusing finger at the country’s policy on the militants but available evidence also indicates covert linkages.

The obvious question is: why is nothing being done about the Lashkar-i-Taiba and Jaish-i-Mohammad leadership when they are in the country and the agencies know about their hideouts? Then there are stories about linkages with some Taliban elements in Waziristan while there is a battle going on with others. Surely, this brings lots of questions to mind to which there are some possible explanations.

First, as part of the war tactic it is not possible to completely end relations with the enemy. There is always the possibility of co-opting some and thus breaking the power of the enemy.Second, there is a conscious plan to resurrect a Wahabi state which would then lead to creating the historical Islamic empire that a number of people dream about. Some such people have also been referred to by the general-president in his speeches in which he talked about former senior military officers with links to the extremists.

The Taliban style of governance is a good method of centralised control of a vital region. This is certainly what many in government and among analysts learned from the Taliban rule in Afghanistan. The defenders of the Taliban in Islamabad used to eulogise them for having brought discipline and peace to a warring society.

These unidentified elements (be they serving or retired) have a vision of an Islamic empire which would be led by the only Muslim nuclear power that is Pakistan. One saw some glimpses of this thought in a paper written almost a decade ago by a group of intellectuals in the GHQ titled ‘Gulf Crisis 1990’ in which the basic thesis was that a power vacuum created by US military losses in the Gulf would be filled by Pakistan.A painfully slow defeat in Iraq or Afghanistan remains a possibility. The departure of Nato and US troops in five years would create a huge power vacuum which will be extremely lethal. The idea is not that the US or Nato should not pull out but that their stay, the use of military force and the lack of clear identification of forces which would like to control the area in the future do not present thrilling conclusions for the country or the region’s future.

It is vital for the people to understand where power resides in Pakistan today. Is the general-president, who claims to be fighting extremism, completely in charge or are there forces and ideas that we do not know anything about? Transparency is essential for restoring the common man’s confidence in his country.

The writer is an independent analyst and author of the book, ‘Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy’.

E-mail: ayesha.ibd@gmail.com

http://www.dawn.com/news/1070536

—————-

DAWN – Opinion; June 13, 2008

Published Jun 13, 2008 12:00am

Comment Email Print

The wannabe heroes

By Ayesha Siddiqa

THE retired servicemen seem to have rebelled against President Musharraf calling for his impeachment and trial for planning the Kargil operation. In a press conference held on June 4, a group of retired servicemen demanded Gen Musharraf’s trial, restoration of judiciary, revision of the Kashmir policy and the revoking of the controversial NRO.

An important point raised during the meeting was to investigate the Kargil crisis which cost Pakistan a lot of money, precious lives and reputation.

While an audit of military operations by the government is certainly needed, the important question which must be asked is that is this press conference just a ‘rebellion’ of ‘civilianised’ army men against the former army chief in defence of democracy and higher political values in the country?

If at all, the ex-servicemen’s call for revamping Musharraf’s political and military legacy indicates a malaise within the political power structure, especially the deeper establishment. Broadly speaking, this indicates the problems which arise with the military’s long entrenchment in politics which is now working against the organisation’s much-flaunted ethos of unity of command.

But before we get into a systems analysis, lets look into the actors who are part of this ‘rebellion’ and whether it is true that they merely acted in defence of democracy and independence of judiciary. It is interesting to note that this club of ‘old soldiers’ struck at the time when Musharraf is engulfed with criticism from all sides.

Notwithstanding the importance of the movement for restoration of judiciary, the intent of the ex-servicemen, especially some of its members could be more than strengthening a civilian institution. So, the onlookers have to be careful in distinguishing between the need to investigate the Kargil crisis and the actual intent of people like Gen Jamsheed Gulzar Kiyani and others in telling the story now. The good general sat silent all these years enjoying his stint as head of Fauji Foundation’s company Marri Gas and then as the chairman of the Federal Public Services Commission. The question is that why didn’t he ask any question then?

One of the features of popular or semi-popular movements is that they throw up all sorts of personalities who join a political race for their own goals. In fact, the dialectics of the political movement of these ex-servicemen wannabe heroes denotes two interesting issues.

First, there is a rift within the deeper establishment and this group of ex-servicemen is just a glimpse of the internal friction. Contrary to the argument that these retired generals, brigadiers and colonels are innocent civilians, the fact of the matter is that they are part of the military fraternity which includes serving officers, retired officers and some civilians as well who are linked with or dependent upon the military’s power. The retired ones, hence, are as much part of the larger institutional politics as the serving officers. It was very clear from the press conference that the real issue was removing an individual than strengthening democratic institutions.

The retired officers defended the economic, political and social power of the armed forces and defended the organisation’s control of the state. They even mentioned the military’s right to ten per cent jobs as granted by the constitution which is an absolute fallacy. The ten per cent quota was granted by Gen Ziaul Haq and is mentioned in the Establishment code of the government and not in the constitution.

What makes the old officers’ attack against Musharraf significant, as mentioned earlier, is that these voices represent the friction within the deeper establishment that is the military. The retired officers serve the purpose of airing views that the serving cannot. While representing one view or the other, these officers represent differing points of views rather than an independent voice. So, while some would air the concerns of the pro-democracy lobby, others speak for the pro-US, pro-China or pro-Islamist views within the defence organisation. The reason that these voices have become louder now is because the friction has increased. Moreover, with the years of engagement in politics of the military what could one expect but for the noises to become more audible?

But why should these people be treated as informal spokespersons of the internal lobbies? This is because the military suffers from the lack of a strong institutional mechanism for internal dialogue. The Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee, (JCSC) which was established during the 1970s to redress this very problem, came to nothing due to the army’s take over in 1977. Gen Sharif, who was the first chairman JCSC, was of the view that the Zia martial law killed the institution. Since then, the three services have used two mechanisms: (a) retired servicemen and (b) media to debate their interests and present their perception. The smaller services also have favourite journalists they can lobby to present their standpoint since they do not have any other option.

Then there is the problem at another level which is the services themselves where different groups and lobbies have to convince the higher command of their point of view. This is where the voices of the retired officers become part of the din. The Kargil crisis itself is an example of the absence of string internal mechanisms for debate and analysis. The retired Gen Kiyani says that even the ISI was not informed about the operation. However, the fact is that a major war-like operation was launched without sitting officers seriously objecting to it. Some will argue that the silence itself is a sign of professionalism. The officers are meant to obey the higher command and not present their views. In the post-colonial military tradition the command of the service chief cannot be challenged. Nonetheless, the officers, who in the past have challenged the higher command on moral grounds, were no less professional or officer-like than those who continued to obey questionable decisions. The three brigadiers who refused to fire on civilians in Lahore in 1977 were real officers.

This discussions, nevertheless, is not about what is a real officer but to make a simple point that the wannabe heroes amongst the retired officers do not necessarily represent an alternative. They have during the course of their careers been part of questionable decisions and it will be sad if they become heroes by aligning themselves with the lawyer’s movement. There should certainly be a trial for Kargil but for all the other sins as well which were committed by many in the course of the country’s history. What is even more important is creation of institutions within the state and the deeper establishment so that we can be saved from unwanted heroes.

The writer is an independent strategic and political analyst.

ayesha.ibd@gmail.com

http://www.dawn.com/news/1071273

———–

DAWN – Opinion; January 02, 2009

Published Jan 02, 2009 12:00am

Comment Email Print

Politics of the media

By Ayesha Siddiqa

LATELY, people have raised questions regarding the independence and ideological tilt of Pakistan’s media. Some have even expressed surprise over the perspectives of a few seemingly liberal anchors.

However, such a view is essentially flawed because it is based on an equally faulty judgment of the media’s overall ideological leanings.

The view of the media as being liberal or conservative, right or left, is based on the position which many in the print and electronic media took towards some recent domestic political issues. Examples of the latter included the debate on the lawyers’ movement and Gen Musharraf’s rule and many of his controversial decisions.

An overall view would make the divide appear thus: first, those supporting the lawyers’ movement and opposed to Musharraf are liberal in contrast to those who back him. Second, sections of the media (this includes commentators) supporting the US against the Taliban claim to be liberal in contrast to those who take an opposite view. The problem with this kind of mapping is that writers, anchors and channels liberal in the first category, appear to be conservative in the second. In fact, post Mumbai most of the media seems to have swung to the centre-right, a shift that confuses everyone who wants clear categories of those holding varying viewpoints.

The question then is how does one begin to view Pakistan’s media and intelligentsia? Issue-based categorisation, as mentioned earlier, is flawed. As a matter of fact, by and large the media in Pakistan is either centrist or right of centre in orientation. Perhaps there is only one anchor who represents the centre-left position.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise because a major expansion in the media took place under the Musharraf regime mainly due to the Pakistani establishment’s realisation that it needed a friendly media for future international encounters. The Kargil crisis, as a friend pointed out, made it clear to Rawalpindi that battles could be won or lost depending on the state’s ability to manoeuvre domestic and international opinion via the media. This is how post-Mumbai developments were approached by building an opinion that the Pakistani state was under tremendous threat. Resultantly, most opinion-makers stopped asking questions about the internal threat.The media’s expansion during the Musharraf dispensation also did not mean that the media would support the former general. The main beneficiary of this expansion has been the establishment which is one of the kingmakers and more powerful than any particular ruler. This also means that a ruler, civilian or military, can be discarded once he or she becomes a nuisance. So, sections of the media could turn against him giving the flawed appearance of being liberal.

Assessing the media’s role and contribution is necessary to bridging the intellectual gap as perceived by the powerful state which has been extremely irked at the thought of the Indian intelligentsia being far more loyal to the state than its counterpart in Pakistan. It is apparent from the treatment of the recent crisis between India and Pakistan that the new media, which represents a major part of the intelligentsia as well, has been much more in line with the establishment on national security issues like its counterpart in India. The manner in which the media played a role in building the war hype and in de-linking the real issue of militancy inside the country from Indo-Pakistan tensions is an example of its peculiar ideological bent.

This is not to suggest that the media should have supported Indian jingoism. However, a more liberal media would have critically investigated the larger issue of militancy within the country. Unfortunately, only a handful of writers and one paper was willing to carry out such an assessment.

Another example pertains to providing tacit support to authoritarian, ideological and cultural traditions. For instance, a few months ago, an anchor of a particular television channel show condoned the killing of Ahmadis. More recently, the same channel showed as part of its breaking news a man in Balochistan walking on fire to prove his innocence in a murder trial before a local jirga.

This is not about selling news and attracting viewers but about deepening the right-wing agenda. After all, the right wing is far more comfortable with authoritarian principles and structures. The political left talks about change and dissent which is increasingly missing from our media. The political battle fought against Musharraf or other generals does not necessarily mean a left-wing liberal orientation. In fact, the battle against Musharraf reflected divisions within the establishment over a man who had to go because he had become too costly for the state.

The new media represented by the electronic version is a potent tool. Interestingly, most anchors who play a major role in moulding opinions are either from urban Punjab or urban Sindh. Owing to reasons that cannot be jotted down in this space, they are observed as being far more closely aligned with the centre-right than many journalists of yore. This goes to show that the right wing-oriented Pakistani state is much more powerful and stronger than it used to be.

Two reasons are behind the strength of the right-wing state: first, the definition of liberalism is wrongly construed within a limited framework, and pacifism and political liberalism or alternative politics are no longer considered part of liberal politics. Second is the gradual weakening of the left in Pakistan.

The breakdown of the Soviet Union caused the weakening of left politics all over the world, especially in Pakistan where it proved to be the death knell for the already weak left. A lot of people who felt the left’s absence either converted to the right by supporting the US and became self-proclaimed liberals, or came closer to the right-wing establishment in the country. It was forgotten that left politics is about a liberal political ideology and supporting a people-friendly agenda.

Although some might argue that supporting Taliban politics is part of representing what people favour, the fact is that we refuse to look at the liberal-left politics which prevails in Latin America at the moment. It is possible to fight America’s political incursion without necessarily pushing state and society towards a far more virulent brand of right-wing politics.

Most sadly, the left wing today has transformed itself into an NGO-style operation with limited capacity to influence public thinking. A right-wing state supported by a media with a similar orientation will only lead to strengthening the political right and weakening the liberal left, if any bit of the latter remains in the country.

The writer is an independent strategic and political analyst.

ayesha.ibd@gmail.com

http://www.dawn.com/news/1071869

Good exposing of this closet Ahrari Deobandi bigot and wannabe class jumper.

http://pakistanblogzine.wordpress.com/2012/08/28/ali-arqam-durrani/