The walking wounded of Waziristan: The lost tribes’ search for spring – by Owais Tohid

It’s springtime in Sadat Ullah Dawar’s beautiful village of Issori. The hills in front of his mud house rise from among the lush green fields, which are covered with blue colour flowers, ‘Sparlah’, bathing the valley with their scent. In the backdrop stands the majestic mountain of Shawal in North Waziristan still covered with white snow. The graying patches show that the melting has begun. The colourful migratory birds flying over the valley stop to drink from the freezing cold waters of the Tochi River before moving on.

Sadat, too, is moving on. He is locking his ancestral home to take his old grandparents — Dilawar Khan and Bi Jan — to the nearby town of Bannu. Unlike the birds, he doesn’t know when, and if, he’ll be able to return.

Crossing the fields, Sadat quietly plucks a Da Sparlay Gul (flower of spring) and keeps in his pocket. Wherever he goes, a small part of home will now go with him.

“All tribesman love their home in the springtime but my Bi Jan says, ‘Son let’s leave because it has become so dark here that one cannot see his own hand.’”

The shadows of darkness to which Bi Jan refers, lengthened in this valley more than a decade ago with hordes of foreign militants moving in from the Afghan border through the rugged hilly terrain and thick jungles of Shawal Mountain from Paktika province and Kurrum tribal belt into Mir Ali.

|

At a private educational refuge for Waziristan and Dawar students in Bannu, these young men spend much time preparing for their exams and keeping an eye on political developments back home.— Photo by Ihsan Khattak

|

The local clerics, whose influence has steadily grown over the years, played on the religious sentiments of the tribesmen, calling on them to host these “mujahideen” out of a sense of brotherhood. Others, who were less idealistic, were lured with money. So the tribesmen welcomed these war-battered and defeated warriors and offered them shelter, believing that they would soon disappear back into the war-torn land of Afghanistan. But the hordes kept coming, first a trickle, then a flood.

Everyday there was a fresh convoy of militants of different castes, creeds and colour. Low key and ‘quiet’, tall and athletic, Al Qaeda militants of Morrocan, Egyptian, Algerian and Sudanese origin. The round-faced, flat-nosed and ruthless Uzbeks; the fair-skinned Chechens. The short Uighur Chinese with their thin scraggly beards. Muslim converts from America, Germany and France known collectively as the ‘Gora Taliban’. Thousands of local jihadis joined their ranks, distinct because of their appearance and inability to speak Pushto, these were the long-haired and short-tempered Punjabi Taliban.

The temporary shelters the militants sought soon turned into entrenched sanctuaries as they allied with local commanders Hafiz Gul Bahadur and Siraj Uddin Haqqani. After forming the Tehrik-i- Taliban, thousands of fighters turned this tribal belt into the world’s most dangerous labyrinth, threatening peace inside Pakistan with suicide attacks and in Afghanistan by fighting US and Nato forces. Soon, the US drones were hovering over the hamlet and raining missiles while the militants unleashed a reign of terror on the ground.

“We have been caught between the earth and the skies,” says Sadat, who has rented a house for his grandparents in Bannu and struggles to set up a transport business there. “The Americans kill us by firing from the skies and men with ugly faces (militants) have made our lives miserable on the ground.”

And then there are the lives those very militants have ended entirely. Sadat recalls his friend Deen Wali, a 28-year-old transporter who was ruthlessly executed by masked militants on suspicion of spying, a day after a US drone attack in which militants were killed. Young Taliban militants pulled him out of his shop and dragged him across the road. “Amriki jasoosi, Ameriki Jasoosi (American spy, American spy),” Sadat remembers the militants shouting as they dragged his friend. “Two of them held his arms and the other two his legs, and tied explosives around the whole body while my friend was screaming.”

The tribesmen, including Deen Wali’s family members, gathered around but nobody dared to stop the Taliban militants. “The militants walked backwards, moving away from Deen Wali, and pushed the remote button. The explosives detonated, shredding him. His flesh and body parts flew everywhere.” The militants left the scene in a convoy of vehicles leaving behind the clouds of dust, despair and helplessness. The regularity of such horrific events such as this compelled hundreds of tribal families to leave their homes. Hundreds of Sadats, Dilawar Khans and Bi Jans.

Now in Bannu, Sadat’s grandfather Dilawar spends his day sitting cross-legged on a wooden takht under a tree on the roadside. Surrounded by the young and elderly tribesmen wearing woollen Waziri or Chitrali cap, they huddle their charpoys around an old fashioned three-in-one stereo recorder to listen to news in Pushto on Deewa and Mashal radio stations. As soon as the news bulletins end, their commentaries and analyses start.

“It’s an international war which has engulfed us,” says North Waziristan’s influential tribal elder, Malik Shad Ameen Wazir. “The volcano is in Afghanistan but it erupts in our tribal areas.”

|

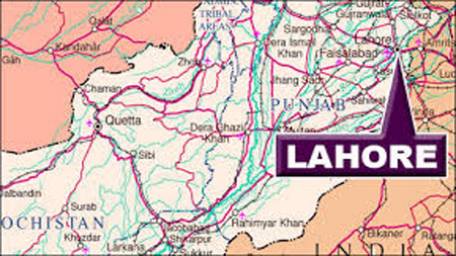

Waziristan: Towns, tribes,lands and population

|

For tribal elders like Shad Ameen, the solution lies in negotiations through what he calls ‘real’ jirgas and not the military operations, drone attacks or even the ongoing peace talks. The tribal elders feel the peace negotiations and negotiators simply do not represent them. “How can the tribal people be represented by the Taliban, who are the very force that tarnished our social fabric, tribal values and traditions? Our hujras are not safe, our jirgas have been targeted,” says Malik Shahden. “We are suffering on every count. We cannot afford unending military strikes on our land, nor do we want to see our land be ruled by Taliban.” Pausing for a moment, he continues: “Our elders had a saying that if a woolen blanket gets leeches, you don’t burn the blanket, you pluck out the leeches.”

Another elderly tribesman laments the experience of displacement. “We tribesmen, who lived for centuries on the mountains, have been made into kochies (gypsies),” he says. He recited a couplet in Pushto, that translates to ‘Our mountains have been burnt so the birds are building their nests on our palms’. “We are now like those birds,” he says.

These wandering tribesmen are now scattered through Bannu, Kohat, Hangu and Peshawar. They carry with them deep invisible wounds of divided families, lost livelihoods and ruptured lives. “I am physically here but my soul is in the valley,” says Gul Saleh Jan. “I lost my young son when my house was bombed. I buried him with my hands, said my farewells, and then left so that my other children could have a future.”

Saleh Jan’s two surviving sons are now studying in Bannu like hundreds of young teenage boys who had come from villages like Hasu Khel, Ippi, Idak, Issori and Hurmuz, all lie in Mir Ali town. These Waziri and Dawar students live in small hostels and study at private tuition centres. But memories and concerns haunt these students. Hakim Dawar for instance, cannot sleep at night as he worries about his father constantly. “He forced me to leave the valley but he is still there among the dark shadows.”

The tribesmen relate that every Waziristani keeps anti-depressan t tablets in their pockets. Sadat takes his grandmother Bi Jan for psychiatric treatment every week. She stopped talking since she left her village of Issori and now sits idle the whole day. “We console her and tell her that the situation is improving just to make her feel better. Today I told her that the village is preparing to celebrate the harvest so after a long time she smiled back at me.” Sadat himself smiles as he says this, though the furrows on his forehead reveal his true state of mind.

Sadat’s grandfather Dilawar Khan wants to go for a walk to Dau Sadak, the main road which leads from Bannu to North Waziristan, and I decide to accompany him. The old tribesman takes a deep breath, filling his lungs with the breeze that wafts in through the valley. “I can smell the Waziristani spring,” he says. I can see Sadat holding the Sparlay Gul he had plucked from the field outside his home, a lifetime ago. The scent may have long since dissipated but it still revives his hope that he might yet go back to the lush green fields, the ice capped mountains, the freezing cold Tochi river, to his own valley — North Waziristan — to enjoy the spring of new beginning. But only once the long, cold winter has finally passed.

The writes tweets @OwaisTohid

Source :