Sunni Ittehad Council: Sunni Barelvi activism against Deobandi-Wahhabi terrorism in Pakistan – by Aarish U. Khan

posted by Abdul Nishapuri | January 18, 2013 | In Featured, Original ArticlesRelated posts: Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC): Peaceful Barelvis rise against the Taliban-SSP criminals

Sunni Barelvi (Sufi Muslims) Struggle with Deobandi-Wahhabi Jihadists in Pakistan – by Arif Jamal

Most of the banned militant terrorist outfits of Pakistan either subscribe to the Deobandi or the Wahabi-inspired Ahl-e-Hadith or Salafi school of thought, while none of them is Barelvi. From 1980 to 2005 the anger of these militant organizations was directed only against the Shi’a community. Even today, militant organizations are targeting the Shi’a population in all parts of the country with bomb blasts and target-killings

Several Barelvi leaders joined hands for an alliance, the Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC), in May 2009 to work and guard against religious extremism and terrorism. The move seemed to be influenced by a gradual escalation of attacks on shrines across Pakistan since late 2006, as well as the on the Barelvi (Sufi) community that venerates these places. Presumably, pro-Al-Qaeda Pakistani militant organizations orchestrate these attacks on places which are frequented by thousands of followers every day. SIC has been able to achieve some successes but in the socio-political maize of Pakistan, this alliance, too, is hamstrung by limitations. This paper attempts to briefly look at the history of attacks on shrines, explain the achievements of SIC and analyze its limitations in an environment loaded with violence and sectarian differences, which Al-Qaeda-inspired militants – also called “Force Multipliers of Al Qaeda” – appear to exploit every now and then.

Introduction

According to the 1998 census, 96.28 percent of Pakistani population is Muslim.[1] These Muslims are further, and mainly divided into Sunni and Shi’a sects. A recent report of the Pew Research Center says the Shi’as constitute up to 15 percent of Pakistan’s total Muslim population,[2] which is a lot less than the estimate of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) which puts Pakistan’s Shi’a at around 20 percent.[3] The predominant Sunni sect is further subdivided mainly into the Barelvi (Sufi) and Deobandi schools of thought.[4] There are no reliable statistics available for the proportions of the Barelvi and Deobandi populations. The Barelvis are, however, estimated to be between 50 to 70 percent of the total Sunni Muslim population of Pakistan and can be differentiated from the Deobandis by virtue of their tradition of veneration of Sufi saints and their shrines.[5] Most of the banned militant terrorist outfits of Pakistan either subscribe to the Deobandi or the Wahabi-inspired Ahl-e-Hadith or Salafi school of thought, while none of them is Barelvi.[6] From 1980 to 2005 the anger of these militant organizations was directed only against the Shi’a community. Even today, militant organizations are targeting the Shi’a population in all parts of the country with bomb blasts and target-killings.[7] In Kurram agency of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), the Shi’a Turi tribe is battling against the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) militants since 2007, when the TTP took advantage of the already tense relationship between the local Shi’a and Sunni tribes inhabiting this mountainous border region. [8]

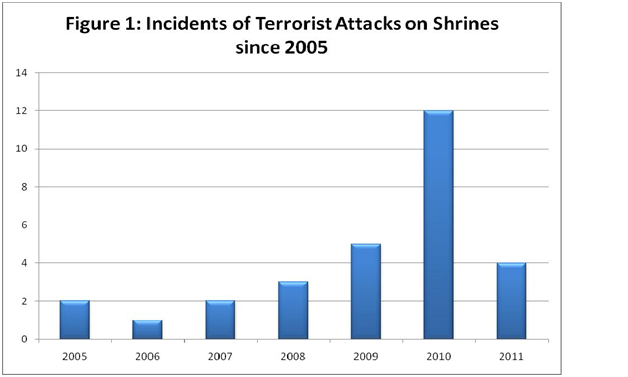

In 2005, however, the militant organizations began going after “symbols” of the Barelvi community such as mosques, prominent religious leaders, and shrines. It began with a bomb blast at the shrine of Peer Rakheel Shah in Jhal Magsi on March 19, 2005, that killed 49, followed by a suicide attack at the Bari Imam shrine near Islamabad on May 27, 2005, in which 25 persons were killed and more than 100 injured. Since then, extremist militants have repeatedly attacked shrines and, at times, Barelvi leaders as well. According to the data of the incidents of attacks on shrines compiled by the Center for Islamic Research Collaboration and Learning (CIRCLe), a think-tank based in Rawalpindi, 209 persons have been killed and 560 injured in 29 terrorist attacks on shrines since the first attack in March 2005. [9] One estimate has put the number of suicide attacks targeting shrines in Pakistan from 2005 to November 2010 at 70,[10] which could not be verified with a timeline though. Figure 1 below, based on the data of CIRCLe, shows a gradual rise in attacks on shrines since 2005. This trend peaked in 2010, while four high-casualty attacks have already taken place in 2011.

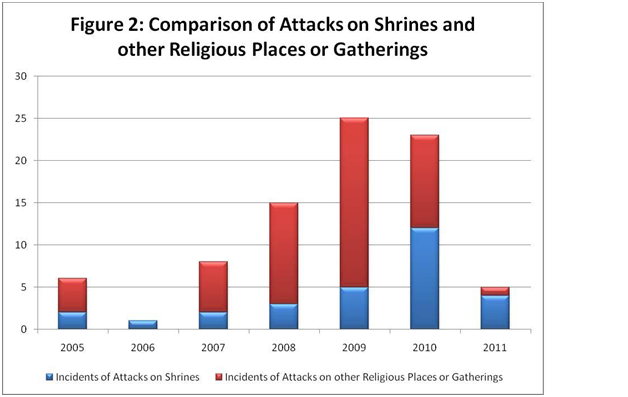

Comparing the data of attacks on shrines with that of assaults on other religious places or gatherings throughout 2005 and 2011, one can ascertain that the numbers of attacks on shrines exceeds those on other religious places or gatherings for 2010 and 2011. Figure 2 below—based on a combination of the data of attacks on shrines obtained from CIRCLe and the data of attacks on other religious places or gatherings provided by an associate of the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), Mr. Nafees Muhammad—illustrates the trend.

The last attack on a shrine, a twin suicide bombing at the shrine of Sakhi Sarwar in Dera

Ghazi Khan on April 3, resulted in the killing of 50 persons and injury to more than 120. One of the alleged suicide bombers —who was caught before he could detonate the explosives tied around him—has made a disturbing revelation that he was training with 350 other teenagers at a camp in North Waziristan. This is reason enough to believe that more attacks against the shrines cannot be ruled out. The attacks on the shrines are generally attributed to the Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith (Salafi) backgrounds of most of the banned militant organizations in Pakistan, which view veneration of shrines by their devotees as a form of worship of the graves and, thus, heresy.[11] Some analysts also argue that militants target these sacred places because of the ideological challenge that they pose to militancy i.e. portrayal and perusal of moderate and peaceful image of Islam.[12] It is true that the idea of Sufi Islam attracted many class-bound Hindus of the subcontinent for its inclusivity and generosity. It was this docility of the Barelvis that kept them away from the Afghan jihad as well as the ire of the jihadist organizations until 2005. At this point in time though, either the ideological appeal, or the perceived heretic traditions, of the non-violent Sufi Islam has become a source of alarm—or at least discomfort—for the militants. Because of their peaceful and non-violent character, the Barelvis were very slow in reacting to their systematic targeting by the militant groups. Their stand against militancy is still in a very nascent stage, and that is one of the reasons many observers are not sure about the direction that it would take. Owing to the uncertainty surrounding the future of Barelvi activism against militancy and the paucity of literature on the subject, this paper attempts to make some initial inroads into the understanding of the dynamics of Barelvi activism against terrorism.

Sunni Ittehad Council: The Face of Barelvi Activism against Militancy

It was in May 2009, that several Barelvi political parties and apolitical groups joined together to form an alliance with a one-point agenda of countering religious extremism and terrorism, called the Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC). This alliance included some important Barelvi groups and political parties like Jamiat-e Ulema-e Pakistan-Markazi (JUP-Markazi) led by Haji Fazle Karim, Jamaat Ahl-e Sunnat (JAS) led by Mazhar Saeed Kazmi (the elder brother of former Federal Minister for Religious Affairs, Syed Hamid Saeed Kazmi), Sunni Tehrik (ST) led by Sarwat Ijaz Qadri, Almi Tanzeem-e Ahl-e Sunnat led by Peer Afzal Qadri, Nizam-e Mustafa Party led by Haji Hanif Tayyab, Markazi Jamaat Ahl-e Sunnat led by Syed Irfan Mashhadi, Zia-ul-Ummat Foundation led by Peer Amin-ul-Hasnat Shah, Halqa-e Saifiya led by Mian Mohammad Hanafi Saifi, Anjuman-e Tulaba-e-Islam (a Barelvi student organization), Tanzeem-ul-Madaris (the Barelvi Wafaq that issues degrees to the graduates of madrassahs) led by Mufti Muneeb-ur-Rehman and represented at SIC by Ghulam Mohammad Sialvi (its Secretary General and former chairman of Pakistan Baitul Maal), Anjuman-e Asaatza-e Pakistan led by Peer Athar-ul-Haq, and several others. Currently, Haji Fazl-e Karim—leader of JUP-Markazi, a firebrand Barelvi leader, and a member of the National Assembly (MNA) on a Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) ticket—is the Chairman of the SIC.

The SIC, since its formation, has achieved certain important milestones against religious extremism. On August 14, 2009, the SIC organized a Peace March in Rawalpindi condemning religious extremism and terrorism and expressing support and solidarity with the Pakistan army battling against terrorists in Swat at the time. The march was attended by more than 10,000 followers, which was an impressive showing for any group raising its voice against terrorists in Pakistan. On October 17, 2010, the SIC organized an ulema and meshaikh convention in Islamabad with the main message of expressing solidarity against religious extremism. Once again, the showing was remarkable with more than 5,000 Barelvi ulema from all across the country participating in it. It ended with a pledge to stage a Long March from Islamabad to Lahore against terrorism on November 27, 2010. The Long March— despite a crackdown by the federal and Punjab governments—succeeded in gathering a sizeable number of people in the twin cities of Rawalpindi and Islamabad on the planned date. The first day of the march also witnessed scenes of showdown between the SIC activists and the police, when the police tried to stop them in Rawalpindi. 150 SIC activists were injured in the clashes with police on November 27 while hundreds were arrested. [13]

Thousands of SIC activists gathered in Lahore on November 28 when the march ended there.[14] SIC’s last conference on April 17 in Lahore gathered around 1,000 muftis from 55 different countries to give a joint fatwa against suicide bombing and condemn attacks on shrines.[15] The SIC has made itself heard and seen in the electronic and print media as a voice against extremism in a short period of time, which is no mean achievement.

All this has made many national and international observers believe that—or at least wonder whether—the Barelvi community in general, and the SIC in particular, can be banked upon as a counterweight to militant extremism from within the religious community of Pakistan. Indeed, the SIC has made some remarkable progress against religious extremism and militancy in Pakistan. It is for the first time that a mainstream religious community has come out in the open against militant extremism. The SIC, as its various shows of force have suggested, has a reasonable number of motivated followers that could be mobilized against terrorism.

The Limitations of Barelvi Activism under SIC

Certain concerns, however, put limits on the SIC as a potential bulwark against militant religious extremism and as a representative organization of the Barelvis in this confrontation. One might spell out these concerns as follows.

• The SIC has left out some important Barelvi organizations like the Dawat-e-Islami led by Ilyas Ataar Qadri and Minhaj-ul-Quran led by Dr. Tahir-ul-Qadri. Both the organizations are the most visible faces of the Barelvi community on the electronic media and among the highly respectable among their academic circles. Some important and powerful Barelvi families like the Makhdooms of Punjab or the Pagaros Sindh have not made many favorable gestures towards SIC either. There are yet other organizations like the faction of the JUP led by Abul Khair Zubair, which has joined the opposite camp. He was part of the six-party (later five-party) religious alliance, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), along with the largest Deobandi political parties of Jamiat Ulema Islam’s Fazlur Rehman faction (JUI-F) and the Jamaat Islami (JI), which do not share the same views against religious extremism with the SIC.

• The SIC has not charted a clear direction for itself yet. The leader of the SIC, Sahibzada Fazle Karim, announced during the Ulema and Meshaikh Convention in October 2010, that they would use SIC as a political platform even though it was initially established as a non-political platform.[16] He reiterated this in the SIC conference in April 2011, in Lahore as well.[17] It often appears that Karim is using the platform for increasing his political mileage, and emerge as a national leader of the Barelvis. This can be determined from the grand announcements that he makes at each of the activities of the SIC. The one on April 17, also witnessed an announcement from Karim of a Train March from Karachi to Islamabad on August 14. This is something that might be raising eye-brows within the Council, as mentioned in the next couple of points.

• No matter how strong, the SIC is still an alliance; it is not a single organization. The diverse organizations that constitute the SIC sometimes have divergent interests or opinions. There are indications of simmering differences within the SIC. During the October 2010 Ulema and Meshaikh Convention, Peer Riaz Hussain Shah, Secretary General of the Jamaat-e-Ahl-e-Sunnat and a senior member of SIC, lashed out against other SIC leaders accusing them of taking money from the U.S. Several SIC members did not participate in the November 2010 Long March as well, despite the fact that the decision was endorsed by them during the October 2010 Ulema and Meshaikh Convention.

• While the SIC claims to be an anti-extremism alliance, their overall posture is pro-Barelvi and, thus by default, anti-Deobandi and divisive. The SIC has, perhaps deliberately, not come up with any gesture of bridging the divide with their Deobandi counterparts. The reason could be their grievances against the latter over not coming up with as strong a commitment against religious extremism and terrorism as themselves.

• So far the stance of the SIC has been very reactionary. Initially, it was like a lethargic lumber of the Barelvi religious leaders and custodians of the shrines that they did not really want to carry forward. Thanks to the successive strikes at the shrines by the terrorists that they have finally spurred into some action. Despite that, however, most of their struggle so far seems to be more of anti-shrine-attack or pro-Barelvi rather than antiextremist, anti-terrorist, and pro-Pakistani.

• The SIC is walking a tight-rope by motivating people—mostly the pumped up youth—to openly vent their anger on the emotive religious issues. When emotions run high, organizing platforms can be hijacked by more violent elements. The Sunni Tehreek (ST), one the constituent parties of the SIC, has a violent track record and is on the watch-list of the Interior Ministry for banned outfits. If there is any serious untoward activity involving ST in future—there have been some not very serious ones in the past—and the Interior Ministry bans ST, it could become very problematic for the SIC to have an organization among its ranks that is declared a terrorist organization by the government.

In addition to these limitations facing the SIC, the Barelvi community as a whole is constrained by its own limitations in the battle against religious extremism and terrorism. Even though it might statistically be the biggest school of thought among the Sunnis in Pakistan, it is not a monolithic whole. The Barelvis in Pakistan are divided into four different families called silsilas that trace their lineage to Prophet Mohammed (PBUH): Qadriya, Naqshbandiya, Chishtiya, and Suhurwardiya. Their system is also rife with nepotism and corruption, which is at times in complete contradiction with the teachings of Ahmed Raza Shah Barelvi, the principal ideologue of the Barelvis in the subcontinent. There are also personality clashes among the Barelvi leaders, as mentioned earlier in the context of the SIC.

Conclusion

Though not grand, yet the SIC has made significant progress in a span of mere two years against the proponents of the militant Islam, largely unparalleled by any other religious organization thus far. Coming out in the open and chanting slogans against Taliban and militants of similar bent of mind in a volatile and insecure atmosphere of Pakistan requires courage and conviction. The SIC has displayed a consistent resolve in its peaceful struggle against extremism, without allowing its limitations to impact or impede its mission. At the same time, while advocating peaceful Islam, the SIC components will have to check violent tendencies within their own ranks as well . The ST in particular would have to tame its violent cadre to appear as an advocate of peaceful Islam. The SIC will also need to chart its future direction carefully, assume a more proactive role, and develop a more universal appeal and vision. It will also have to take a clearly defined line of action, emphasize greater inclusivity, commit itself to internal accountability, and improve its networking.

References

1 Population Census Organization, Government of Pakistan. Data available at www.census.gov.pk/Religion.htm last viewed on April 28, 2011.

2 Pew Research Center: Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population, The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, October 7, 2009, p. 10.

3 CIA – The World Factbook at www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world factbook/geos/pk.html last viewed on April 28, 2011.

4 The Ahl-e-Hadith or Salafi school of thought is also practiced in Pakistan, but its followers are a small minority.

5 Both Barelvis and Deobandis follow the Hanafi School of Islamic jurisprudence and have a lot of commonalities with one another.

6 One of the Barelvi organizations, Sunni Tehrik, is on the watch-list of the banned organizations of Pakistan’s Interior Ministry. It is discussed a little later in this paper.

7 For details see Lawson, Alastair: “Pakistan’s evolving sectarian schism” BBC News, January 25, 2011 at www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-12278919 last viewed on April 28, 2011.

8 According to a news report a truce was signed recently in Kurram, see Butt, Qaiser: “Kurram agency: after years of fighting, jirga brokers truce” in The Express Tribune Karachi, January 30, 2011. It is not guaranteed, however, that this truce would last, because many such ceasefires in the past have not sustained for long.

9 The data can be accessed at

www.terrorismwatch.com.pk/images/Timeline%20Of%20attacks%20on%20Shrines%20In%20Pakistan.pdf last viewed on April 29, 2011.

10 Tohid, Owais: “In Pakistan, militant attacks on Sufi shrines on the rise” in Christian Science Monitor, November 5, 2010.

11 Tohid, Owais: “In Pakistan, militant attacks on Sufi shrines on the rise” in Christian Science Monitor, November 5, 2010; Jamil, Mohammad: “Who is behind attacks on shrines” in Pakistan Observer Islamabad, April 5, 2011; Imtiaz, Saba: “Targeting symbols or spirituality – II” in The Express Tribune Karachi, September 26, 2010.

12 Murshed, S Iftikhar: “Sufism and the terrorist scourge” in The News Islamabad, April 12, 2011.

13 Urdu language daily Nawa-i-Waqt Lahore, November 28, 2010.

14 “SIC ‘save Pakistan’ long march ends in Lahore” in Daily Times Lahore, November 29, 2010; see also Urdu language daily Nawa-i-Waqt, November 29, 2010.

15 Urdu language daily Nawa-i-Waqt Lahore, April 18, 2011.

16 “Sunni Ittehad Council to hold long march for peace” in Daily Times Lahore, October 18, 2010.

17 Urdu language daily Jang Karachi, April 18, 2011.

Writer has worked as a Research Scholar at the Institute of Regional Studies (IRS), Islamabad, since September 2002. He holds a Master’s Degree in Political Science from Peshawar University

Source: View Point

The watches once was analog in nature until the onset of digital watches from various vendors, Highly from Japan. These digital watches had many features integrated within them for instance the day and date display, Reserved alarms, By the hour alarms, Stopwatch advantage etc.