Pakistan: A Failed State?

Seventy years on from its creation, crisis-ridden Pakistan is a very different country from the one envisioned by its founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Pakistan is the first of only two modern states to be created in the name of religion. The second, Israel, declared its independence on 14 May 1948, exactly nine months after Pakistan’s creation on 14 August 1947. At the end of the Second World War, with Europe’s global empires collapsing, various new nation states emerged, founded on notions of territorial nationalism, language or ethnicity. Pakistan is, and remains, different because of the ideology that is its raison d’être: Islam and, to a lesser extent, the Urdu language. It is this difference that has made establishing a modern nation state difficult. As the historian of Pakistan, Ian Talbot, has written, the 70 years following Pakistan’s creation have shown that ‘language and religion, rather than providing a panacea for unity in a plural society, have opened a Pandora’s box of conflicting identities’.

Religious ideology was to be the glue that would inflexibly bind Pakistan’s otherwise disparate sociocultural identities: at the country’s conception, it was understood to be Islam in a holistic sense. The sectarian divisions and the prevailing dominance of Sunni Islam, which has hardened in the years following the country’s creation, were not foreseen. Pakistan’s minorities, who include Christians (the largest group), Ahmedis, Hindus, Sikhs and a small number of Parsis, live in a country where ethnicity, caste and kinship are overridden by this religious ideology, enforced by a state that pays no heed to the country’s plurality.

While modern nation states in Europe emerged from the decline of medieval Christendom with a clear division between religion and politics, Pakistan’s experience has been exactly the opposite. Its first 70 years have been largely defined by the rise of the religious right and its siege of the nation state. Yet, in the beginning, Islamists were against the creation of Pakistan. How then, have they taken control of the path the country has taken? For the answer, five key moments across the country’s short history emerge as significant landmarks in defining what Pakistan is and what it might become in the future.

Jinnah reads a copy of the Pakistani newspaper Dawn, published to mark his 71st birthday, 25 December 1947.

Jinnah reads a copy of the Pakistani newspaper Dawn, published to mark his 71st birthday, 25 December 1947.

1949: Jinnah’s Lost Vision

On 11 August 1947, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founding father of Pakistan and leader of the All-India Muslim League since 1913, gave a speech to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. Founded in June 1947, the Constituent Assembly was created to formulate the new country’s constitution and serve as its first parliament. In his speech, Jinnah clearly defined the role of religion in a modern nation state, where freedom of religious practice was the undisputed right of every citizen. Jinnah’s clear-headed and secular vision for the new nation was not predicated on the idea of religion. Instead, he envisaged Pakistan as a diverse, democratic state. The crux of the speech is encapsulated in a few sentences:

Now I think you should keep that in front of us as our ideal, and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State.

The notion that Islam would be the cornerstone on which Pakistan would be formed had been central to the argument for a separate state since March 1940, when the quest to establish Pakistan began in earnest. Yet here, days before Pakistan became a reality, its leader asserted an inclusive agenda for the new country. Jinnah, the political visionary, saw a way of reconciling the contradiction that arose from the idea of a nation state founded on the principle of religious identity, but his death, just over a year later in September 1948, meant his vision would not be realised. The Pakistan that emerged in 1949 was not that foreseen by Jinnah, just as modern India does not mirror the vision of its founding inspiration, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. It is a feature of contemporary South Asian politics that the visions of the founding fathers have been compromised and hijacked by succeeding generations.

From 1949 onwards, a clear deviation from Jinnah’s vision of an inclusive Pakistan took place. The modernist reformist Aligarh Movement – so called because it originated in the north Indian city Aligarh – was founded towards the end of the 19th century with a twofold aim. To engage Muslims with western scientific thought and to reconcile the concept of God with the secular concept of a nation state. Until 1949 it was accepted that the Aligarh Movement would drive Pakistan forward. However, it was upstaged in 1949 by two events, which would take the country in a different direction.

First, was the establishment of Majlis-e-Tahafuz-e-Khatm-e-Nabuwwat (MTKN). Translating as ‘The Assembly to Protect the Finality of Prophethood’, the MTKN was an offshoot of the Majlis-e-Ahrar-Islam, a religious Muslim political party founded in 1929, which had strongly opposed the creation of Pakistan. The Majlis-e-Ahrar had contested the 1946 elections against the Muslim League, with a manifesto based on the repudiation of the idea of a separate Muslim state, but lost convincingly. Once Pakistan had been founded, the party’s leadership opted for a low-key presence in the new state. From 1947 to 1949, it stayed in the shadows, but, in 1949, rebranded as MTKN, it re-emerged. Following Jinnah’s death, the version of Islam that gained currency in Pakistan sprouted from the exclusionary and puritanical interpretation propagated by the MTKN.

The second event was the passing, on 12 March 1949, of the Objectives Resolution. It is likely this would never have come to pass if Jinnah had remained alive, as Justice Muhammad Munir argued in his book From Jinnah to Zia. Passed under the Muslim League prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan, the resolution proclaimed that Pakistan’s future would be modelled on the doctrine of Islam, rather than any European model. The Objectives Resolution was instrumental in giving a religious orientation to the state. Its first clause, ‘Sovereignty lies with Allah’, raised fears among the Constituent Assembly’s Hindu representatives from East Bengal that they would be treated as second-class citizens and also alienated the large Hindu minority in East Pakistan.

The Objectives Resolution was presented and passed in a hurried manner, with any reservations being brushed aside. Joginder Nath Mandal, the Hindu president of the first Constituent Assembly and Pakistan’s first law minister, was so disgusted by the absolute lack of reverence for the rights of minorities exhibited by his colleagues that he resigned and left Pakistan. The Objectives Resolution, he declared, indicated that Pakistan after Jinnah was not the nation Jinnah envisaged. Minorities felt suffocated and threatened in this Pakistan, unlike the security they had been promised by Jinnah. Thus, the proposed reconciliation of nation state and religion was defied and the cleavage between the two ideas was brought to the fore.

1953: The Rise of the Right

Having re-emerged from the shadows, the MTKN began to make its presence felt in 1953, when it orchestrated the launch of anti-Ahmadiyya agitation, culminating in a mass movement demanding legislation to declare the Ahmadiyya as non-Muslims. The Ahmadiyya Community was a movement founded in 1889 in Punjab to follow the teachings of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835-1908). Its deviation from mainstream Islamic thought meant that many Muslims considered the movement to be heretical.

The 1953 anti-Ahmadiyya movement failed to achieve its objective, but it did launch the political careers of several religious clergymen. Some had entered politics earlier, but had no prominence until this time. After 1953, clergy became mainstream political leaders, a phenomenon that has had far-reaching consequences in South Asian politics, but which has somehow evaded scholarly attention. This has been the most important and historically influential consequence of the rise of the MTKN: the emergence of the religious right in Pakistani politics and the gradual diminishing or exclusion of various progressive, leftist or even centrist political groups.

Indeed, while the anti-Ahmadiyya movement was gaining strength, the Pakistani state was on a feeble footing. It had to contend with an acute wheat crisis in 1952-3, a major challenge for the central government, which became distracted from dealing with the challenge posed by MTKN. There were other issues to face. The government was stricken by internal rivalries. There were riots in East Bengal, where the Bengali Language Movement was agitating for recognition of Bengali as an official state language. The popularity of the Muslim League was also dwindling and a civil-military oligarchy was forming, which rendered the state vulnerable to political instability. There were seven governments in Pakistan’s first 11 years of existence.

1971: Division and Expulsion

East Pakistan seceded to become Bangladesh in 1971. This was a hugely significant event on several counts, not least in terms of the country’s relationship with India, which worsened considerably. The separation of East Pakistan was soon portrayed as a Hindu (read ‘Indian’) conspiracy and, as the Hindu-Muslim dichotomy was exacerbated, the position of the religious right, as well as the army, was legitimised. One of the biggest effects of the division has been the consolidation of majoritarian religious tendencies in Pakistan. When East Pakistan was part of the federation, minorities formed 23 per cent of the population. With the secession of Bangladesh, this number was reduced to less than three per cent. It was after the creation of Bangladesh and the subsequent decline in minority groups that the conception of an Islamist Pakistani ideology gained firm footing and took on the pervasive and all-engulfing character witnessed today.

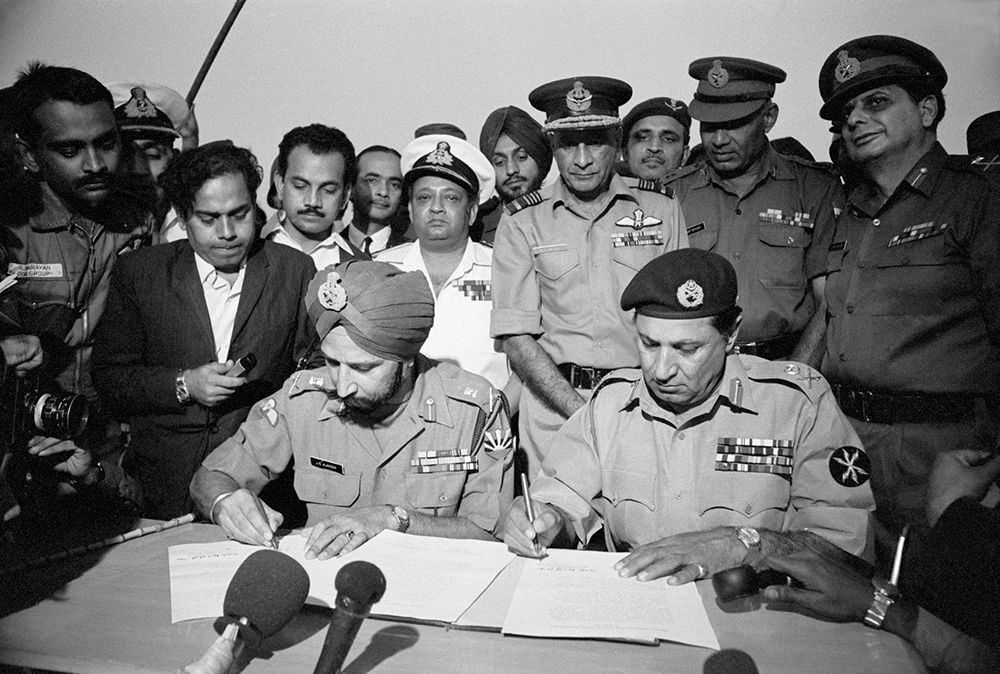

Lt Gen Jagit Singh Aurora, (left) and Lt Gen Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi sign the peace treaty that turned East Pakistan into Bangladesh, Dhaka, 1971.

Lt Gen Jagit Singh Aurora, (left) and Lt Gen Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi sign the peace treaty that turned East Pakistan into Bangladesh, Dhaka, 1971.

One manifestation of this occurred in 1974, with the constitutional declaration of members of the Ahmadiyya community as non-Muslims. The movement that had failed in 1953, but boosted the cause of the religious right, now succeeded. It was unprecedented for such exclusionary legislation to be moved in parliament, passed and made a part of the constitution. More remarkable is that it happened under the democratic rule of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, leader of the left-wing, progressive Pakistan Peoples Party. That it could be passed was testament to the growth of the religious right’s influence. Under Bhutto’s rule, the MTKN was able to reconstitute itself; its success in 1974 convinced the religious right that it could exert pressure over the elected parliament through extra-parliamentary tactics.

In 1974, students from Nishtar Medical College in the Punjab city of Multan were on a trip when their train stopped at the small Punjabi town of Rabwah (now Chenab Nagar), home to an Ahmadiyya headquarters. The students, many of whom belonged to the student wing of the Islamic political party Jamaat-i-Islam, began chanting anti-Ahmedi slogans, leading to a physical confrontation between them and the Ahmedis. This small incident would lead to the exclusion of the Ahmadiyya people from Islam. In a few days, a nationwide movement had started. Initially, Bhutto hesitated, but the MTKN threatened his government with direct action. In order to avoid confrontation with the religious right – which had great ‘street power’, having mastered the politics of agitation during the days of the British Raj – he decided to go with the flow. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto took this extreme measure to appease the religious class, but in doing so gave credence to the religious right’s disruptive message that political issues should not be resolved through negotiation. Instead, threatening and blackmailing would be substituted for negotiation and compromise. Such tactics have determined the subsequent course of Pakistani politics.

1979: Revolution Abroad, Unrest at Home

Bhutto’s concession did not appease the religious parties for long and would spell the end of his premiership. Their street politics, following claims that the 1977 elections – which Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party won – were rigged, created the circumstances for military intervention. On 4 July 1977, Bhutto was ousted in a military coup known as Operation Fair Play. Its leader, General Zia ul Haq, used Islam to legitimise his draconian rule, replacing Bhutto’s populist regime with authoritarianism couched in the garb of religious terminology. Then, two years into his regime, developments on Pakistan’s borders occurred which were to further shape its domestic development, with long-lasting consequences.

First, the revolution in Shia Iran, orchestrated by the Shia imam Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, mobilised Pakistan’s minority Shias. Then, in December 1979, the Soviet Union occupied Afghanistan. Pakistan was converted overnight from being a pariah state in western eyes to a frontline state in the struggle against Communism. Zia was provided with the opportunity to extend his rule and unfurl in public his agenda of Islamisation.

The Iranian Revolution encouraged the Shias to flaunt their sectarian identity, an ominous development for Pakistan’s Sunni-led state. Expressions of Shia identity provided an excuse for Sunni Saudi Arabia to intervene in a bid to halt Shia enthusiasm. Several seminaries (madrassas) were granted financial support by Saudi Arabia and many new schools were set up at the Saudis’ behest. As a consequence, sectarian identities in Pakistan crystallised. The sectarian divide became even more pronounced when the Zakat and Ushr Ordinance was issued by the Zia regime. One of the Five Pillars of Islam, zakat is a religious obligation on alms giving, or tax, for all Muslims of certain wealth. The ordinance was enforced on the insistence of Saudi Arabia and its draft was prepared with the help of a Saudi scholar, Dr Maruf Dualibi. Shia jurisprudence dictates that zakat does not have to be paid to the state, though this was exactly what the Zakat and Ushr Ordinance proposed. As a result, Pakistani Shias marched on the capital, Islamabad. Led by the Imamia Students Organisation (ISO), 50,000 Shias protested in Islamabad for several days, until the Zakat and Ushr Ordinance was partially revoked and Shias were exempted from zakat deduction.

The successful attempt to get zakat revoked encouraged the Shia community to form a sectarian organisation, Tehreek-e-Nifaz-e-Fiqh-Jaffariya (TNFJ), in 1979. Sectarianism became an established political reality and spread from political to social and cultural realms. In 1985 the Anjuman-e-Sipah-e-Sahaba party was founded to counter the Shiite influence. Sectarian reading of religious texts became the sole identity marker for a citizen of Pakistan. Theological differences not only increased intolerance, but also led to violence as Pakistan was awash with weapons from the Afghanistan conflict and religious parties developed militant offshoots.

With the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, Zia ul Haq saw an opportunity to join the US-led war in Afghanistan. Zia’s detractors argue that he joined the war only to perpetuate and legitimise his dictatorial regime. The counter-argument, however, holds equal weight. The strong legacy of Pakistan-US collaboration, with the former being a signatory of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) in 1954 and the Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO) in 1955, could not be ignored by the government. In reality, Pakistan did not have any option but to join the US-led war against Soviet Russia in Afghanistan, but its decision to do so had several ramifications: drugs, weapons and religious extremism flooded into the country, culminating inevitably in sectarian clashes.

The darkest side of the agenda of Islamisation initiated by Zia was the promulgation of the Hudood Ordinance, passed in 1979. Public flogging was introduced for crimes, which now included adultery and fornication. The state became an overbearing Orwellian Big Brother, keeping close tabs on the morality of its citizens. The archaic Hudood laws led to the infamous Blasphemy Laws, whereby it became routine for false accusations to be levelled against religious or sectarian minorities and even at times against personal enemies. Zia also left a legacy of mob justice. If Pakistan at 70 appears a less evolved nation state than others, it is his legacy that has hindered its progress.

2001: The World After 9/11

Zia’s death in a plane crash on 17 August 1988 helped to usher in the 1990s with optimism and comparatively liberal social norms. However, though Pakistan was free from Zia’s repressive regime, his legacy of deeply entrenched sectarian and ethnic violence remained. The political musical chairs between the country’s recently deposed prime minister, Nawaz Sharif of the centre-right Pakistan Muslim League, and the Pakistan Peoples Party’s Benazir Bhutto throughout the 1990s furthered the rise of the religious right, which Bhutto tried to rein in but could not. When these musical chairs culminated in General Pervez Musharraf’s military coup in 1999, at first it appeared that a progressive, liberal agenda would replace the Zia policies. Musharraf was in many ways the antithesis of Zia, yet the events of 11 September 2001 put his Pakistan on a new course. Joining the US-led alliance in Afghanistan after 9/11, Musharraf followed in Zia’s footsteps in more ways than one. The most debilitating of these was his need-based reliance on the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal, a political alliance of far-right, conservative religious parties, which helped him forge an electorally feasible coalition.

The coalition ensured that he remained the real head of government, while appeasing international demands for the restoration of democracy with the October 2002 general election. This allowed him to keep Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto out of the country, while their parties ostensibly remained part of the political process. In the absence of their leaders, however, those parties failed to check the advance of the religious parties, which entrenched themselves even further into the body politic of the nation state. This reliance on religious politics aside, Musharraf made a critical revision to the state policy when, as a result of 9/11, he took a hard stance against extremism and sectarianism. Such was the radical nature of his clampdown that reactionary forces, strengthened over the previous decades, retaliated viciously in the form of suicide attacks. The resurgent religious right now projects these as the inevitable aftermath of what it believes to be Pakistan’s flawed policy of siding with the US post-9/11. Yet, just as Zia could not shrug off the baggage of Pakistan’s historical alliance with the United States, Musharraf could not take a different route from US policy either. The post-9/11 adjustment in state narrative was a compulsion and not a choice.

Future Tense

The real bane of Pakistan’s existence in its first 70 years has been the rise of political religiosity, which has undermined the development of the nation state. It has formed a culture of intolerance, sectarianism and the ever-increasing need to keep religious forces well-provided for. Musharraf’s realisation of the need to halt this rise and the religious right’s commitment to resist any such change are best manifested in events surrounding the Red Mosque (Lal Masjid) of Islamabad.

Red Mosque, Islamabad, 2008.

Red Mosque, Islamabad, 2008.

A powerful sectarian seminary established in the Zia era, the Lal Masjid operated in open defiance of the federal government and its administration. Its followers had proclaimed themselves enforcers of religious law, which they took into their own hands, carrying out public punishments on those they considered to be in violation of Shariah law. When, in July 2007, the state decided to end the activities of Lal Masjid clerics, it met with unexpected resistance. The operation uncovered a hidden basement where militants were trained, housed and hidden.

It was this operation and the killing of prominent cleric Rashid Ghazi and arrest of his brother Abdul Aziz which led to the series of suicide bombings in Pakistan that continue to this day. And it was in the wake of the Lal Masjid affair that disparate jihadist and sectarian groups came together under the umbrella of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan. Unlike its Afghan counterpart, the Pakistani Taliban has targeted elements of the Pakistan state and, increasingly, ‘soft’ civilian targets. The battle for Pakistan’s future continues.

Source:

https://www.historytoday.com/tahir-kamran/pakistan-failed-state

its not the state that’s failed, its the ruling political elite that has failed the state. clear difference between the two. the idea “Pakistan is a failed state”, was first introduced by the Indians and it has taken root over the years even in Pakistan, a failed state does not have a functioning army, a navy, and an air force nor does it produce first class engineers, business men, bankers etc.