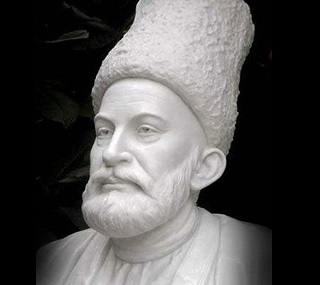

Ghalib: The Grand Poet from India – by AZ

Years ago when I needed a book that I held in great esteem to take the oath of allegiance to my adopted and beloved country the books that I instantly thought worthy of such deference were ‘The Complete Works of Shakespeare’ and ‘Diwan e Ghalib’. In the end I chose Diwan e Ghalib. In the hindsight, it was probably not so much an act of homage to the great man as, on a deeply personal level, an act of atonement and a pilgrimage, an effort to overcome in my own life the sense of inadequacy many of my generation have felt growing up in such culturally nondescript climes. I find it interesting that Ghalib, and so much else of the subcontinent’s cultural heritage, has survived despite post 1947 generations. While no writer equals Shakespeare in any of the languages I am familiar with, I opted for Diwan e Ghalib because no single piece of work of a similar size can withstand years of careful examination and unhurried reflection like this small book – a collection of Ghalib’s Urdu poetry.

Ghalib’s writing and life illumined and mirrored the different facets of human existence, its hopes, disappointments, tribulations, diversions, confusions, pettiness, grandeur, connection, achievements, temptations, compunctions, and despairs in a manner rarely seen even among the masters. Thus, in Diwan e Ghalib we can find almost all aspects of human wisdom and thought, every warning we need to hear, every misery we detest, and every joy we need to cultivate. Pondering over Diwan e Ghalib at a young age developed my muscles of thoughtfulness, the use of which is the greatest pleasure in human life as it shows what it means to be fully human.

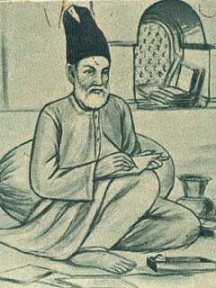

Ghalib lived in Delhi through a fascinating period. Mughal power was fast fading away. The British had established themselves as rulers in all but name. Ghalib, who prided himself in being a part of feudal nobility, was torn between his loyalty to the Mughal Empire and the need to cultivate the new rulers from whom he sought his monetary sustenance. He has reflected the sentiment with remarkable imagery.

“My struggle resembles what doth captive birds engage

Gathering twigs to build a nest still in their cage”

The period of Mughal decline coincided with a phase of unmatched literary efflorescence spurred by Urdu’s emergence and popularity at the expense of Persian. This manifested itself in many ways, one of which was the powerful sway of Sufi customs and secularism over Delhi’s way of life. Ghalib’s works mirror Delhi’s tribulations and pains to eternal literary greatness. Ghalib’s vision of the past stood in prickly contrast to his indigence in the present. Not unexpectedly, he fancied to invoke the past in protest against the present. One sign of this syndrome was his emphatic and overt preference of Persian over Urdu in a time when Urdu had largely eclipsed Persian at popular level. Urdu was the fashionable and vibrant language of his time, exhibiting the effervescence and energy of a young language that had come into its own, both in literary terms and as the lingua franca. There was a profound piquancy in the situation as a literary renaissance in a modern language was taking place within a decaying and stultifying feudal-monarchic order desperately clinging to Persian. Hence, Ghalib did not view writing in Urdu as an accomplishment as he viewed doing so as lending legitimacy to the situation. There was a point when Ghalib almost stopped writing in Urdu for about thirty years.

Ghalib wrote many classical letters and made sure even his conversations were handed down to posterity. Altaf Hussain Hali paints a vivid picture of the poet’s life and times, and is worth reading on this account. His guiding thread is that Ghalib did not believe one should privilege intellectual issues over more bodily, immediate ones. Mind thus was not more important than the body because neither could exist alone. To be fair, Ghalib was clearly concerned with the details of everyday life and found satisfaction in them. He liked his glass of wine, took time to suggest cures to friends when they fell ill, enjoyed a pretty face, and loved dance. However, rather than sending us on a journey toward personal happiness, his works often warn against paths of self-indulgence and self-delusion. By infusing philosophical knowledge into his mode of thinking Ghalib provided that inner impulse which is so characteristic of his thought. It was not by rejecting a genuine study of nature, but by working in harmony with nature, that he wished to reach the heights of a spiritual conception of the universe. We shall only understand this inner impulse aright if we follow the movement of ideas in his epoch, and if we realize that within this cultural environment Ghalib’s aims and ideas met with no response. For this reason Ghalib is nearer today to those who are seeking knowledge of the spirit. He often felt himself a stranger to his age; whereas every seeker after the spirit feels himself perfectly at home with him today.

Ghalib asserted the validity of all life’s experiences and summoned for the courage to enjoy them all despite the inevitability of sorrow and trauma being a part of them. For him life was to be savoured in all its hues as long as one was alive:

“O heart, regard even sorrow’s hymn to be of solace

For one day, this existence will descend into utter silence”

“The hand may be unmoving but the eyes can still see

Leave the cup and the wine yet placed before me”

Ghalib would rather welcome pain then sequester himself from the colour and spectacle of life in its plenitude to avoid misery:

“If it is not by now asunder thrust a dagger and pierce the heart

If thy lashes are not soaked in blood pick a knife and pierce the heart”

“The heart that is not aflame is a disgrace in the bosom

If each breath is not on fire the heart is mortified”

“Like the reflection of a hunched bridge in torrent, be happy in disaster – dance

Extricating thyself from thyself, keep thyself poised – dance

The search itself is a delight, so why fret over the end of the journey?

At the sound of camel-bell be not afraid to wobble – dance

Even the howling of an owl should sound like a melody

Even in the tempest of the phoenix fluttering wings – dance

The pleasure of the desert’s immensity cannot be found in love

Become a whirlwind of dust and mounting in the air – dance

Shove aside the old-fashioned traditions of thy honoured friends

Grieve in the wedding feast and in the assembly of mourners – dance

Unlike the rage of the pious and the friendship of the hypocrite

Be not self-centred, but in the full view of all – dance

Search not sorrow in burning, or enchantment in blooming

Be it blustery tempest or gentle breeze, abandon thyself – dance

Ghalib with this exultant joy to whom art thou bound?

Wax great in thyself alone, don the fetters of disaster – dance”

Ghalib took great delight in poking fun at the hypocrisy of the religious self-righteous:

“The entrance to pub and the preacher are indeed poles apart

All I know is yesterday I saw him enter as I walked out to depart”

Ghalib thought that a preoccupation with religious appearances dulled compassion, produced intolerance, and inhibited spiritual growth.

“One who is intoxicated with the lust for reward has to struggle with heaven and hell

But he who longs for only His bountiful mercy sees no distinction between the flame and the rose”

He relished targeting the sentinels of orthodoxy:

“Proud of what special wisdom are the pretenders of perception

When they are merely fettered by constant ritual and convention”

Ghalib had a profound faith in eclecticism, holding all humans as symbols of divinity and love of the one Almighty. The most inspired example of his catholicity is his Persian poem ‘Chiragh e Dair’ exalting the splendour of the temple city of Banaras. In a letter to a friend he wrote, “I wish I had renounced the faith, taken a rosary in my hand, put a mark of abnegation on my forehead, tied a sacred thread on my waist and seated myself on the bank of the Ganges so that I could wash the contamination of existence away from myself and like a drop be one with the river.” This is absolute synthesis, manifesting the spiritual quest completely liberated from the limitations and parochialism of organized religion and rendering the bulwarks of religions irrelevant.

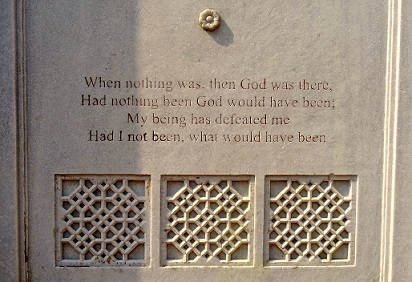

The Unity of Existence was a matter of deep intellectual conviction for Ghalib.

“In faith we are monotheist and all rituals we abjure

Only when symbols vanish doth faith become pure”

Ghalib subscribed to the unity of faith in its purity:

“Unfaltering devotion is the heart of all faith

If the Brahmin passes on in the temple, inter him in the Kaaba”

The intellectual integrity and the conviction that suffuse Ghalib’s secular outlook enable him to state:

“In the Kaaba I will play the conch-shell

In the temple I have wrapped the ‘ahram’”

Eclectic Ghalib had devious ways to undermine parochialism in beliefs:

“While faith pulls me back, disbelief tugs at me

The Kaaba is behind me, the church in front of me”

Ghalib repeatedly manifests a profound sense of detachment from the temporal experience:

“Asad, do not be ensnared by the being’s deception

The world is nothing but a ruse of thought and conception”

“In dream though did thought with you bargain

Upon awakening, there was neither loss nor gain”

“In the mirage of existence do not get caught

While it seems it is, in truth it is naught”

“That which seems emergent is in fact veiled

He who awakes in a reverie is still in a dream”

He can see divinity all round him and views the Absolute as munificence incarnate:

“By the heat of the sun is the dew taught of its end

I too am until a benevolent glance consigns me to nothingness”

“A hundred visions are there to be seen should one raise the eyelids

But who has the strength to stand the bounty of the spectacle”

“The Glory which suffuses all creation from earth to heaven

Drunk in its magnificence are the most minuscule crumb and atom”

“The evidence of His unity is instituted in His multiplicity

All the innumerable figures have one common denominator”

“This effulgent radiance is the basis of thine continuation

A fleck not caught in the rays of sun is destined for extinction”

“The bead, the wave, the froth, the vortex – all are countenance of the stream

The contention of this ‘I’ and ‘Mine’ is nothing but a screen”

Ghalib could not stand hypocrisy:

“Ghalib cannot be blemished with the mark of hypocrisy

His patched robe washed in wine is spotless”

Ghalib thought the enduring joy lies only in the consciousness of the real essence behind the transitory phenomena:

“To leaves, branches, and stems only the root grants the essence

All that bears articulation stems from silence”

Ghalib articulates how wrapped up in the tiniest of daily struggles one yearns for spiritual transcendence:

“Oh God, how long must I suffer the lowliness of craving

Grant me the loftiness of hands raised up for praying”

Ghalib enjoyed his drink. His personal preference was French wine:

“Like offerings of flowers see my speech surge

If only someone sets a goblet of wine before me”

“Once the tavern is not accessible then for place what objection?

Be it a mosque, a place of learning, or any other accommodation”

Later in his life when there was a scarcity of wine, Ghalib had to grudgingly make do with the satisfying qualities of rum:

“To the last residue we imbibe even if it is Jamshed’s cup that is presented

Shame on that liquor, which from grapes is not fermented”

I will never betray an oath I took upon Diwan e Ghalib, “so help me God”.

Source: