The Myth of Civilian Failure – by Ayesha Siddiqa

posted by Shahram Ali | January 18, 2015 | In Newspaper Articles

What does it mean to mourn the death of 132 children, and the 9 adults tasked with protecting them? One month on, the tragedy that should have paved the way for an honest conversation about the roots of militancy has instead strengthened an easy and flawed narrative of civilian failure, and a dangerous call for army intervention.

The attack on Peshawar was not the first of its kind. In 2009, 137 people, mainly women and children, were massacred in Peshawar’s Meena Bazaar in another brutal militant attack. For a variety of reasons—the timing of the attack, the current make-up of the armed forces, the fact that it explicitly targeted children as well as the army itself—this attack is being treated as a watershed moment, or a turning point of sorts.

I agree with the “better late than never” argument for action that has emerged in the wake of Peshawar, but fear that it is not accompanied with a sober and honest diagnosis and approach to terrorism. In fact, too many political figures—politicians, activists, and analysts—are throwing their hands in the air, some arguing that a military-led solution may be the only way forward. Politicians, they argue, are unwilling and unable to seriously address militancy. And, they add, given that the military started this problem to begin with, they may be the only ones who can “[Change] Titanic’s course”.

Mourning, I argue, lies not in knee-jerk reactions and simply in calls for bloody revenge through military courts and death sentences, nor in an abdication of democratic processes, but in a commitment to systematically thinking through the roots of the violence that has ravaged our country, and what can be done about it. According to a popular narrative, which has emerged in the last five or six years, political parties have links with militants and are too weak to deal with them, and the civilian judiciary has proven unwilling and incompetent in punishing them.

There is some truth to these accusations. After all, Chaudhury Iftikhar, the former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, released Malik Ishaq, the leader of Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ), in 2011. And, Chaudhury Nisar Ali Khan, the current interior minister, has just admitted that 95 banned militant groups operate in Punjab. The continued existence of militant groups, a growing number of spectacular and smaller attacks, and low conviction rates are the strongest indicator of the foot-dragging and incompetency, it is argued, of our civilian leaders. In fact, not long before Peshawar, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who was asked about militancy in Punjab by Dawn journalist Cyril Almeida, vehemently refused to admit to the existence and growth of militancy in Punjab.

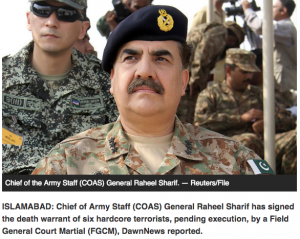

It is believed that army officers may have the solution. The evidence of their commitment includes statements subsequent to the attack (including, e.g. that the good/bad Taliban policy is a thing of the past), the operation in North Waziristan launched this summer, and the carte blanche that they have given to drone strikes. The current army chief, General Raheel Sharif, is more willing to fight the war and punish those that attack the army unlike his predecessor General Ashfaq Pervez Kiyani. We are witnessing, it is argued, a realignment of ideology and interests within the armed forces.

Such a narrative, however, lets our armed forces off the hook, and wrongly puts the bulk of the blame on the shoulders of a civilian leadership that has neither initiated nor sustained militancy within Pakistan. In fact, as long as the army’s larger geo-strategic goals of strategic depth in Afghanistan and rivalry with India do not change substantially—an intervention that, according to a report by Saeed Shah of the Wall Street Journal, was attempted by the prime minister before protests erupted against his government but subsequently squashed by the army—we will see little, if any, change in the problem of militancy in Pakistan. These geo-strategic interests prompted initial flirtations with militancy and they have guided the army’s policy towards them ever since.

An unholy alliance: The army’s militant friends

In my work on militancy over the last few years, I frequently heard police officials complain about the interference of the army or the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) every time they arrested a militant. A police officer in Bahawalpur that I spoke to and who was in charge of an operation against JeM, told me that he could not keep its members imprisoned despite the organization’s vocal threats to “flow rivers of blood” through the city.

The police officer, who is a good friend and was posted in Bahawalpur in 2002, also told me that Masood Azhar, the leader and founder of JeM, told the government in charge “not to divert JeM’s attention” away from external jihad to events within the country by trying to arrest them. In 2002, the senior police official had arrested about 35 JeM militants for hijacking and terrorizing a bus driver and his passengers, but was asked to let them go by the security forces. Intriguingly, the matter was only ever reported in Bahawalpur’s local press, and never made it onto the pages of the national media. The story of JeM, and the sustained presence of other militant groups in Punjab, reveals a far more sinister truth about the roots of militancy in Pakistan.

There are three factors, which guide the army’s approach towards Punjabi jihadis.

First, with these groups firmly based in Punjab, the military is afraid of a blowback if they decide to wage a war against these jihadis. General Kiyani resisted launching an operation in Punjab precisely because he feared that the situation would get out of control.

Second, the army does not feel an immediate need to tackle the issue, especially if these groups are not bleeding the country, or more accurately, the armed forces. Instead, there has been an effort by both the armed forces and the government to mainstream these parties. The Punjab government had made efforts to bring the Sipah-e-Sahaba (SSP)/LeJ network into mainstream politics by involving it in elections and working closely with leaders like Maulana Ludhyanvi and Malik Ishaq. And, some police officers that I have spoken to, who have dealt with LeJ’s other leaders, believe that they would not attack the state. They say that attacks like the one on the Sri Lanka cricket team are a thing of the past.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, groups like JeM, Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), SSP, LeJ, etc.—operate as proxy militias for the armed forces. Many, such as the JeM, have in the past guaranteed security in the areas where they are based, which translates into no attack on state infrastructure. However, security of the state did not guarantee security of religious minorities. Despite JeM’s split from Harkat-ul-Mujahideen headed by Fazlur Rehman Khalil in 2001—prompted by a decision to not to target Shias—evidence1 shows that its members occasionally indulge in sectarian violence especially in partnership with or support from other Deobandi militant organizations like SSP and LeJ (when I interacted with many of the JeM members the anti-Shia bias was visible).

In fact, the two latter groups have members that have proved to be more difficult to control, many of whom have gone to join the Afghan Taliban2 in the past. Instead leaders like Malik Ishaq of the LeJ, and Shafiq Mengal who has worked closely with the same group, continue unabated. Ishaq’s whose group is involved in sectarian violence all over the country including the killing of Hazara Shias in Baluchistan. And, Shafiq Mengal is a notorious figure among Baloch separatists, who accuse him of atrocious abductions and killings of their student activists (including the mass grave discovered in Khuzdar in the beginning of last year).

Relations with India are not at their best. Indeed, the very same General Raheel Sharif who has been reported as the man who will clean up the mess created by his institution may be less willing to change the equation with New Delhi. Lest we forget, his elder brother Shabbir Shareef died fighting India in the 1965 war. Though his brother’s death need not deter him from seeking better relations with India, public voices known to be close to the army seem to be singing the same tune they have for years. Hafiz Saeed, Pervez Musharraf, Hamid Gul, Zaid Zaman Hamid and others have gone as far as accusing India of masterminding the Peshawar attacks. Do these de facto army spokespeople have any evidence linking India with the attack? Or, is involving India as the hand behind the tragedy a more sellable project than simply accusing the Taliban?

The army does not seem to be in a rush to take on all militants, especially those within Punjab, despite their key role in perpetuating violence within Pakistan. Tackling militants in Punjab, Sindh and Baluchistan is largely left to politicians that have shown no excellence in dealing with the matter. This is irrespective of the news on January 14, 2015 that the government was considering banning the Haqqani network and Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD). It will be interesting to watch how far the government or the military will go in implementing such a policy especially when JuD’s Falah-e-Insaniat Foundation (FIF) undertakes major welfare operations in Sindh and Baluchistan in cooperation with the state. Not too long ago, Hafiz Saeed announced, on social media, that FIF would divert its attention towards a draught-stricken Sindh and start projects in Balochistan. According to the National Action Plan (NAP), the government would also restrain militant presence on social media. However, both JuD and Ahle-Sunnat-Wal-Jamaat (ASWJ) continue to operate. The evidence of any concrete action and its authenticity is critical.

A closer look at the actions that have been taken by the army, and that seem to offer some semblance of hope to those now accepting an army-led policy, indicates that they align not only with the difficult job of fighting militancy, but also with the strategic interests of our country’s most powerful institution. One week before the operation was launched, the U.S. Congress linked one-third of the aid given to Pakistan through the Coalition Support Funds to “military operations in North Waziristan that have significantly disrupted the safe haven and freedom of movement of the Haqqani network.”

A few days ago, John Kerry, the secretary of state for the U.S., made an unannounced stop in Pakistan to give the state a pat on the back for their continued operations in North Waziristan. This does not necessarily reduce the decision to fight militancy within Pakistan to U.S. pressure, but it does indicate that we have a tendency to fall back on those pressures, rather than doing the difficult work of figuring out our own way forward. Rather than seeing the operation in North Waziristan as an operation that was long-awaited, or one that was embedded in a larger fight against militancy, we need to accept that there did not seem to be a policy in place to eliminate all forms of militancy despite claims by Major General Asim Saleem Bajwa, the head of Inter-Services Public Relations (or ISPR, the public relations agency of the armed forces) who said he would not spare any militant. Nor was there any indication that the army would go after all militants in the country, especially those hiding in the urban centers and in Punjab. No one was arresting militants from the hotbeds of terrorism around the country.

Moreover, a broader and more comprehensive tackling of militancy means confronting it as more than just a question of arresting and prosecuting jihadis. Why do we assume that the militancy machine will grind to a halt with click of a boot, especially when we are dealing with so many young men recruited in the name of jihad?

Today, groups like LeT, LeJ and JeM have penetrated public sector universities in Punjab where they have student wings and provide financial assistance to students, and thus gain access to a fresh, young and educated crop of men (and women). There are hundreds and thousands of people trained in one form or another as militants. The LeT ran an extensive program for years that even provided basic military training to women. The number of trained LeT members, which vary from the fully trained to those who have done Daura-e-Amma (basic training), could range from 200,000 to 500,000.

The JeM has followed a similar strategy, recruiting what they see as quality jihadist young. Its chief, Maulana Masood Azhar worked extensively to produce his magnum opus Fathha-ul-Jawwad, an exhaustive treatise on jihad according to the Qur’an. The JeM members, who opt for Daura-e-Khas (special jihad training) are men who have qualified in Daure-e-Tafseer in which they spend 30 days understanding Azhar’s book. After arresting their leaders—a task that the state remains too lax at—what will we do with the hundreds of thousands of young men who have been trained as jihadists? Is there an alternative and a method of reintegration for them? Or rather, before we even speak about alternatives and reintegration, is there even any plan to tackle these groups?

We are told that we should accept a military-led strategy because we have no other choice in an environment where our civilian leaders are incompetent, unwilling and scared. Though they may not be as scared, there is no indication that the army possesses the will that they have been assumed to have, nor the competency to think through an anti-militancy strategy that can work.

Instead, the death penalty, military courts, and the ramped-up offensive in Waziristan—a place forced into invisibility—has allowed the army to pretend like it is serious. By keeping trials a secret, executing men who are already in prison, and carrying out an operation in an area where no one can check on their progress, the army can pretend like it is making progress.

Tragically, for the one million who have been displaced by the ongoing operations, and for the millions who have already been forced to move from other parts of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), we have decided to give the army a carte blanche instead of keeping them accountable (Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan has already cleared the army by saying that they never kill women and children.) One gets the sense of an American post–9/11 environment that Pakistanis have been among the first to criticize, where residents of North Waziristan are treated as warring tribals who do not deserve to be treated as human. Those, who like this magazine, investigate army neglect and atrocities are seen as a nuisance focusing on unfortunate casualties, or as outright treasonous.

Yes, it is true that the myth of civilian failure is not completely off the mark. But the army will not save us. Some of the most important conversations—on everything from the enormous military budget, which has played a key role in funding the very militants we are fighting now, to the geo-strategic interests which have fuelled both narratives within and protection of militant groups—are being avoided, and will make it difficult for us to solve this problem. This is certainly not a popular argument. Many believe that such questions can wait for later. However, if the Titanic is to be saved from sinking and made to sail on, these issues must be tackled and alternatives created.

Source: