Salafi and Deobandi roots of violence in Gojra and Larkana – by Ayesha Siddiqa

The writer is an independent social scientist and author of Military Inc.

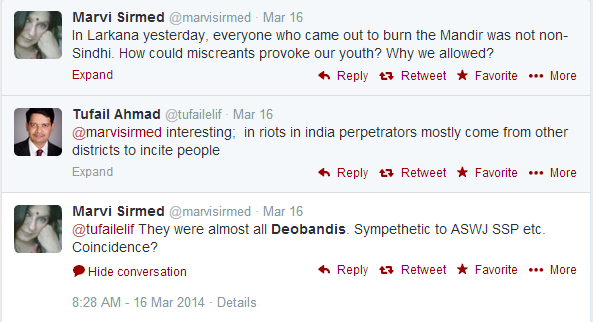

In an opinion piece written recently on the attack on a Hindu temple in Larkana, the writer was of the opinion that the issue must not be taken too seriously. Larkana is not Gojra, Punjab. Thank God for that! But Gojra didn’t happen in a day. The burning of the Hindu temple is an indicator of the gradual transformation of, what was once, a peace-loving society. Like Charles Napier, who sent a telegram after winning the final battle in this area, saying that “I have sinned”, indeed, the extremist forces have Sindh and will gradually challenge plural sociocultural norms, just the way it happened in South Punjab.

The presence of hundreds of Sufi shrines and the fact that the province has a large number of Hindus will eventually not make any difference. It is still the only province where fairly large-sized Hindu religious festivals take place and the community is part of the middle and upper-middle class. However, things have gradually begun to change. The cases of both forcible and consented conversion, especially of Hindu females, have increased, resulting in rising numbers of outbound migration. There are still people, who resist and raise a voice, but this cannot be construed as a sustainable bulwark against an increase in the extremist mindset, especially when militant networks and religious parties are increasing their political and social presence.

The attack on the Hindu temple under the garb of punishing blasphemers is probably nothing more than an attempt to create chasms within society to consolidate political gains made consistently by the religious right. Lest we forget, five religious parties got an impressive number of votes during the 2013 elections. The 376,105 votes of religious parties were two per cent of the 4,742,169 total votes cast. In 2002, the MMA bagged about 11 per cent of votes cast in Sindh.

Broadly speaking, there are three factors that sustain extremism in this province. First is the support rendered by the powerful and permanent institutions of the state to certain militant forces mainly for strategic benefits. The gradual growth of Salafi militancy is certainly a result of this policy. While the Rangers stop everyone else, there is little control over the spread of the LeT/JuD network and their graffiti in border districts. Secondly, the opportunity provided by the state to numerous militant groups to play a role in providing welfare services during the 2010 and 2011 floods has helped legitimise these elements. The LeT/JuD network in lower Sindh, particularly in areas with a sizeable Hindu population, means that there is a slow but gradual building of a base for the Salafi ideology. The network is currently not in a rush to convert Hindus. It probably intends to buy enough time to legitimise its social presence. So, if the Hindu population in these areas does not object, then why would others? The process of social and political legitimisation is critical to the Punjab-Sindh model of militant expansion.

Finally, political legitimacy is sought through building political partnerships between non-religious parties and those of the religious right of a particular ideological brand. Here, the reference is to years of political alignment between the PPP and the JUI-F, which forms the political backbone of the Deobandi militant network. Over the past five years and more, the JUI-F has encompassed most of upper Sindh, expanding into Balochistan. This is a development worth watching because most Deobandi militant networks tend to creep into the province under the umbrella of political parties these are ideologically aligned with. The influence is further buttressed by connections with strong business and other mafias. Political involvement, in particular, is part of the process of building a support base, which in turn, is vital for developing a strong power base in society.

This is not an anomaly because this is exactly what happened in Punjab. The Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) was grounded in the political legitimacy of its prominent leader, Maulana Haq Nawaz Jhangvi. He was part of the MRD movement and contested the 1988 elections on a JUI-F ticket against Begum Abida Hussain. The construction of the militant apparatus of the SSP was aided and abetted by influential individuals from the transport and construction mafias from Jhang. Later, the deep state and its foreign allies in the Middle East also joined in.

The militant networks use the cover of ideologically aligned religious political parties to their own advantage. The dependence continues up until militant networks and their leadership can launch themselves more forcefully. Not that the alignment between the militant and political cadres comes to an end but then militant networks tend to become relatively independent, often even chipping away the social influence of their political platforms. So, the influence and support base, which we find in Sindh in the form of the JUI-F, currently spearheaded by leaders like Senator Khalid Soomro will bolster the clout of Deobandi militant outfits that right now are parked in the shadow of this right-wing political party. In this regard, the JUI-F leadership in Sindh plays the same role as the JUI-F did in Punjab. The performance of Khalid Soomro in Larkana is worth watching. He received 15,730 votes in the 1993 elections. The total votes cast for all forms of religious parties that year were 21,238 against Benazir Bhutto’s 59,376. In 2002, Soomro received about 32,000 votes

Viewing the JUI-F’s votes as a percentage of total votes cast is a flawed perspective. These are hardcore ideological votes, which means that there are enough people who genuinely believe that attacking a minority’s place of worship is their religious duty, especially if it involves blasphemy. The PPP must not target all and sundry as it did in reaction to the religious parties’ gains in 1993. This will make militant forces even more popular. Nor is running away an option. A strict implementation of the rule of law and bringing culprits to justice is imperative for strengthening a counter-narrative in this province.

In case leaders have lost the plot, they must not forget that this act is the beginning and not the end. Sadly, the alignment with the JUI-F, allowing expansion of the madrassa network and not resisting ideological expansion is coming home to roost.

Source : http://tribune.com.pk/story/684820/is-larkana-not-gojra/

I’m really impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Anyway keep up the excellent quality writing, its rare to see a great blog like this one today..

nike femme air max 90 http://www.gpscoordinates.eu/tempo/profile.php?pid=10368

Cool post very informative I just found your blog and read through a few posts although this is my first comment, ill be including it in my favorites and visit again for sure

Ray Ban Prescription Glasses For Cheap http://www.51kara.com/mymessage.php?Nkey=1047

The best formula for men you may find out about straight away.

These kind of post are always inspiring and I prefer to check out quality content so I happy to finally find many excellent point here in the post, writing is simply great, thank you for the post

nike mogan 3 id http://www.flickoramio.com/10690-232.html