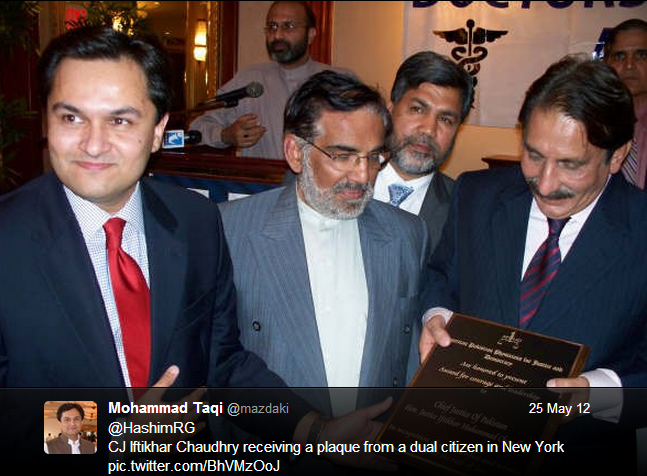

In pictures: How did Pakistanis on Twitter pay tribute to Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry on his retirement?

On his retirement on 11 December 2013, an overwhelming majority of Pakistanis on Twitter, from diverse ethinc, faith, sect, and class backgrounds, expressed pleasure on the departure of Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, the most controversial and disgraced top judge in Pakistan’s history.

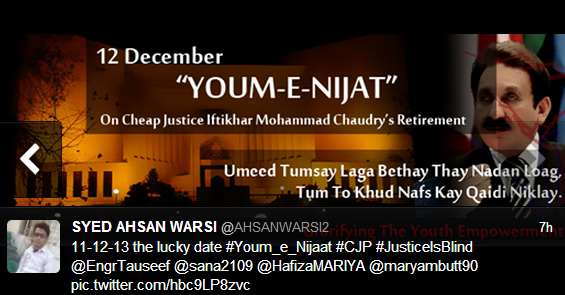

For most of the part on 11 and 12 December, the #YomeNijat or #Youm_e_Nijaat (Deliverance Day) were the top Twitter trends in Pakistan.

Post by S K.

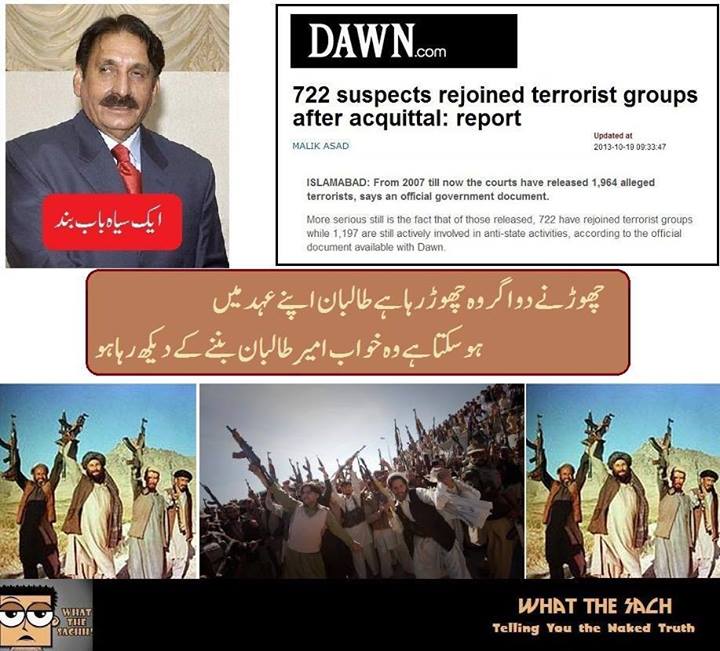

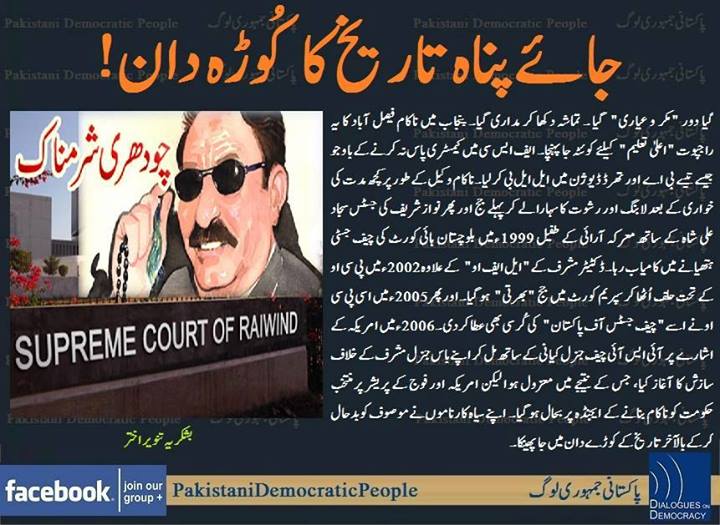

Here’s a collection of pictures posted by Pakistanis on Twitter and facebook as a ‘tribute’ to now retired CJP Iftikhar Chaudhry:

Post by S K

Comments

Latest Comments

It seriously is a youm e nijat. Good riddance!

I think new one will be like him. Geo TV is already trying to lure the new CJ so they can continue avoiding taxes by getting Rs. 300 stay order from court.

مسٹر سو موٹو کا آخری دن۔

جان کی امان پاوں تو عرض کروں ۔۔۔’

جاتے جاتے یہ تو بتا کر جاو ، ارسلان افتخار کیس کا کیا ہوا؟

حمزہ شہباز کیس کیا ہوا ؟

نواز شریف کیس کیا ہوا ؟

زرداری کیس کیا ہوا ؟

میمو گیٹ کیس کا کیا ہوا ؟

راجہ رینٹل کیس کا کیا ہوا ؟

سزا موت پانے والے افراد کا کیا ہوا ؟

جیو نیوز کے کیس کا کیا بنا ؟

کراچی ٹارگٹ کلنگ کا کیا بنا ؟

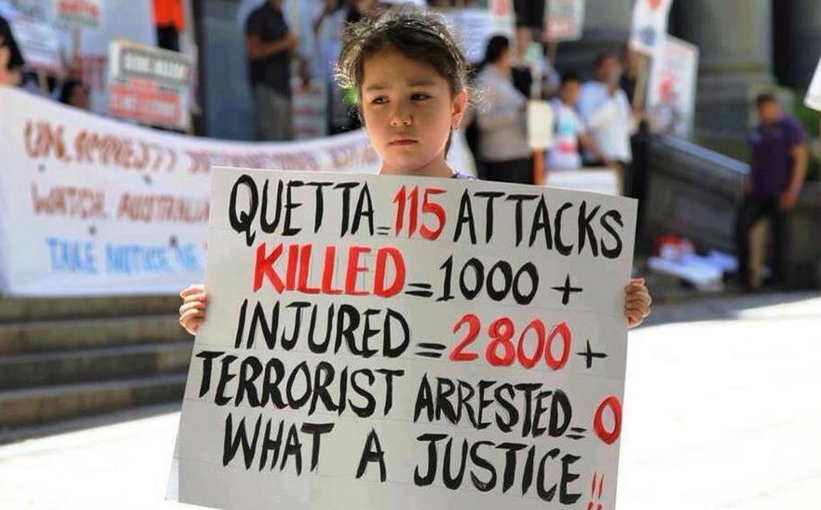

کویٹہ ہزارہ برادری کو کتنا انصاف ملا ۔؟

گلگت بلتستان کے معصوم لوگو کے گلے کاٹنے والے کدھر ہیں ؟

مسیحی بھاییوں کی بستیاں اجاڑنے والے کون تھے ؟

بنوں جیل، پشاور جیل توڑ کر بھاگنے والے دہشتگرد کہاں گیے ؟

بدنام زمانہ دہشتگرد ملک اسحاق کی سزاوںکا کیا بنا ؟

لا پتا افراد کے سلسلے میں کسی فوجی نے آپکے دربار عالیہ میں شرکت فرمای ۔؟

کتنے افراد آپ نے بازیاب کرانے کا شرف حاصل کیا ؟

ڈرون حملے ۔

رشوت کا بدترین نظام ۔

مہنگای کی قیامت ۔

چوری اور ڈکیتی اور ملاوٹ ۔

پولیس کا تباہ حال نظام۔

وکلا کی من مانیاں ۔

غریب آدمی کے صدیوں سے لٹکے ہوے عدالتی کیس۔

۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔۔آپ تو یہی کہیں گے کہ ان پر تمام کیسز پر عدالتی کاروای جاری ہے ۔ اور ہمیں امید ہے کہ یہ جاری ہی رہے گی مگر فیصلہ نہی ہوگا اور ہوا بھی تو عمل درآمد کروانا تو خیر آپ کا کام ہی نہی ،آپ کا کام تو سوموٹو لینا اور

عتیقہ اوڈھو کے پرس سے شراب کی بوتل برآمد کروانا تھا ۔

ایک ایم پے کے تھپڑ کا جواب سو موٹو سے دینا تھا ۔

ایک رینجر والے کی گولی کا جواب بھی سو موٹو ۔

کاش ۔۔ آپ کسی عورت کے پرس سے شراب براآمد کروانے کے بجاے پاکستان میں موجود ہزاروں مدرسوں اور دہشتگرد ٹھکانوں سے بارود براآمد کرواتے ۔ایک تھپڑ کے بجاے گلے کاٹنے اور بوری میں بند کرنے والوں کو سولی پر لٹکاتے تو میں بھی آپ کی شان میں قصیدے پڑھتے ہوے آپ کو جیو والوں کی طرح پاکستان کا ٹنڈولکر کہتا ۔ (عارف گردیزی

source: facebook

The SCP under cheap Justice Iftikhar Ch. was independent………… INDEPENDENT FROM ANY CONSTITUTION or LAW

I am glad that worst days of Pak Judiciary are over. I pray to Allah, that there would be no more person like I.M Choudhry. His legacy will curse him forever. He was not only enemy of Shias, he was also enemy of all out faiths, except the Salafais and Wahabis.

…Baray baray Ali kay naam ki waja say halakat say bach gae tm bhi lay laitay naam-e-Ali tu aaj yoon halakat may na partay….

Caset Dismissed

– by Badar Alam

Institutions, like human beings, do not have roles set in stone. Both evolve over time. Both change in tune with the changing times in which they exist. When an institution gets inexorably linked to a human being, or vice versa, any evolution or change in one reflects itself in the other – and immediately. This is exactly the case of outgoing Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry and the Supreme Court of Pakistan under him.

As he retires today, eight years after he assumed the office of the Chief Justice of Pakistan, no state institution – not even the military, which for most part of Pakistan’s history has been the ultimate arbiter of national politics — dominates the national scene as completely as does the Supreme Court. So does Justice Chaudhry. He has lectured all and sundry on public morality, issues stern warnings almost daily to errant officials, has peddled a populist nationalism on issues of economy and national security and has never tired of reminding anyone within earshot that he has been adjudicating in the name of, and for, the common man.

From the security of the state (suo motu notice of the memo which allegedly threatened the very existence of the country) to the safety of the citizens (hearings on law and order in Quetta and Karachi), from prices of onions to the privatisation of the Steel Mill, from corruption in government departments to questions about the legitimacy, as well as the ability, of an incumbent administration — his has been an all encompassing domain. Except that anyone harping on all these themes day in and day out should sound like an opposition politician rather than an exalted custodian of the law and justice. (Does Justice Chaudhry plan to enter politics once constitutional restrictions against that are no longer valid is a question many of his friends and foes are already asking.)

Justice Chaudhry, however, has done more than just what an opposition politician would or could. He has wielded complete authority, unrestrained by any checks and balances, to set everything right in the image of his own, decidedly populist, ideals. In sound bites and headlines, he has provided self-declared solutions for every single problem that Pakistan is facing. Each of these remedies, though, has had one main ingredient: judicial authority and oversight over everything else. The government can freely go about doing its business as long as it does not annoy the court always quick to take offence. A prime minister can appoint and transfer officials at will as long as the honourable lordships allow him to do so. The Parliament has the power to enact any laws as long as the Supreme Court approves of them. Occupiers of the high offices can work with complete autonomy with the only condition that they will serve at the pleasure of the superior judiciary. (Once they lose that mandate, the Supreme Court will ask their subordinates to lodge cases against them and launch probes against them.) It is entirely another matter that all these pronouncements have done little to achieve their declared objectives of improving governance, putting the economy back on track, providing relief to the people struggling to cope with inflation and raising the quality and the capability of the legislature. If anything, they have won Justice Chaudhry innumerable brownie points and a massive amount of media coverage.

In this he has been helped by a great advantage he enjoyed over prime ministers, their cabinets, the Parliament and other functionaries of the state. He has had all the power; others have had all the responsibility. It is, indeed, a great constitutional and democratic ideal achieved though in a perverse way: Functions are now divided neatly among the institutions of the state. That this division has resulted in a massive gain for Justice Chaudhry and the Supreme Court he has lorded over is not for him to be bothered about.

As he has been reminding all of us in his farewell speeches that he has turned the Supreme Court into the saviour of last resort for the poor and the needy, Justice Chaudhry, indeed, has been on a one man mission to rid the country of all its social, economic and political ills – that is, by his own claim. Whether people have actually benefited from his stint as the head of the superior judiciary as far as removing multiple inequalities in the state and the society is concerned is definitely a matter of serious debate. His critics and detractors would go to the extent of arguing that the courts, over the last few years, have actually failed to perform their basic function – of delivering justice and adjudicating on litigation involving common people. They have instead been all focused heavily on politically significant cases. These critics cite how, under Justice Chaudhry’s watch, cases have been piling up at all levels of the judiciary; they also point out rampant corruption among junior judges and other court officials and lament the absence of any initiative for carrying out some reform of the dowdy, creaking and overburdened legal and judicial system. Some bar associations and their office-bearers have, in fact, gone a step ahead and blamed the superior judiciary of turning a bad situation worse. They allege that many have been appointed as high court judges not on merit but because of their links with a certain group of lawyers close to Justice Chaudhry.

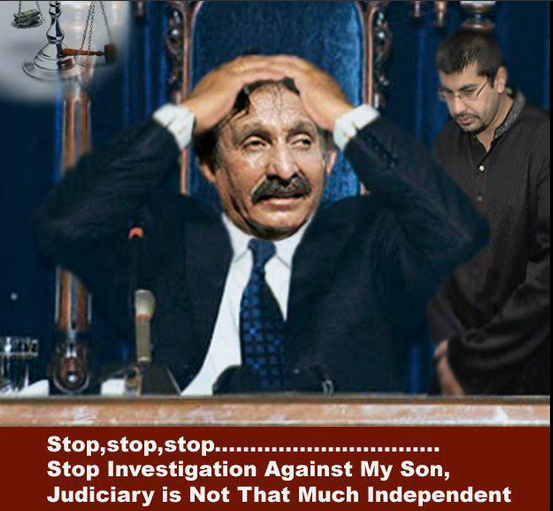

All this has been made possible by a single factor: Justice Chaudhry and the Supreme Court have been above any accountability, since at least 2009. When the Supreme Court decided in mid-2007 against hearing a presidential reference against Justice Chaudhry, he – and by extension, the Supreme Court — has made it clear that nobody has the authority to hold him, and the Supreme Court, accountable no matter what. When the case against his son came up for hearing in 2012, judicial norms and procedures were easily set aside and no one dared challenge or change that. Those who protested against the apex court’s real and perceived “excesses” were promptly served with contempt of court notices. The registrar of the Supreme Court never allowed the Auditor General of Pakistan to carry out an audit of the court’s funds. While the Supreme Court under Justice Chaudhry passed a judgment against extending the tenures of government employees beyond their retirements, he did extend the tenure of one fellow judge at least once (and wanted to extend it for a second time too) and helped the Supreme Court registrar to stay in his job even though he has long passed the age of superannuation. Again, no serious questions allowed on both counts.

Such predominance of one institution, indeed of one man, above all else has resulted in a steep price for our fledgling democracy to pay. The executive stands shriveled and the parliament has been rendered irrelevant. Is all this worth what the country has got in exchange?

The sum total of achievements of Justice Chaudhry and the Supreme Court during his tenure as the Chief Justice of Pakistan has been nominal, though screeching headlines and rambunctious talk shows would have you believe otherwise. The disqualification of many elected representatives over fake degrees, dual nationality and other electoral procedural laws has not tilted the electoral field even by a narrow margin in the favour of the pious and the truthful patriots; all the multiple headline grabbing corruption cases have not resulted in the conviction and imprisonment of any political big shots; few, if any, missing persons have been set free from the detention of the intelligence and security agencies which Justice Chaudhry, on his second last day in office, declared illegal (no official, however, has so far been charged, let alone convicted, for keeping people in illegal detention); law and order in Karachi and Quetta has followed political, ethnic and sectarian dynamics in the two cities despite all the eloquence on the reasons thereof emanating from the superior judiciary; and the taxes declared illegal by the court have ended up burdening the economy with more budget deficit and consequently more debt and more inflation — both indirect taxes for all intents and purposes. Above all, the huge hoopla over the Supreme Court’s verdict against the National Reconciliation Ordinance (NRO) has resulted in no serious proceedings against any of the ordinance’s 8000 or so beneficiaries. Let us not even talk about the possibility of resumption of the Swiss cases against former president Asif Ali Zardari.

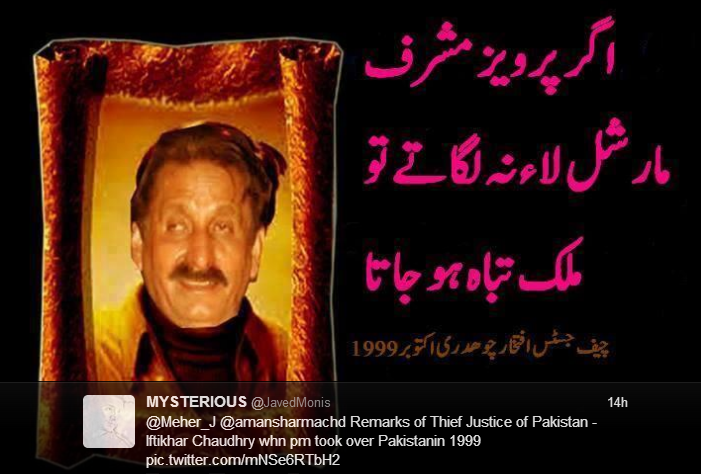

Much has been made of the Supreme Court’s verdict against judges who took oath under the Provisional Constitutional Order issued by Pervez Musharraf in November 2007 and another verdict which binds all judges to not cooperate with any military or non-military dictator in the future. Whether the two decisions serve as a genuine impediment to a military takeover of power in the years and the decades to come will only be decided when these judgments face their real test. History, however, suggests that the superior courts and their learned judges have always found ingenuous ways to bypass previous judgments and judicial precedents when it comes to justifying and legitimising a dictatorial takeover of power. Will they behave differently next time they are told by a dictator to take an ultra-constitutional oath? My guess is as good (or bad) as anyone else’s.

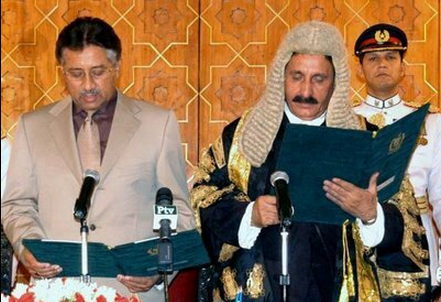

That brings us back to the relationship between the individual and the institution. When Justice Chaudhry first became the Chief Justice of Pakistan in 2005, the superior judiciary was as pliant as it always has been under the dictators and Justice Chaudhry was as obliging as many of his predecessors have been during military regimes. Then, the situation took a dramatic turn in 2007.

Since then the legitimacy, independence and power of the Supreme Court have risen and fallen in tandem with the waning and waxing fortunes of Justice Chaudhry. The legitimacy of the Supreme Court became a function of his legitimacy (remember how the court under Justice Abdul Hameed Dogar enjoyed hardly any popular legitimacy); independence of the judiciary became synonymous with his independence (other deposed judges would refuse to resume their jobs unless he was restored to his post) and all judicial powers came to be vested in his person (there has been never — yes, never — a dissenting note in any of the high profile Supreme Court judgments delivered since his restoration in March 2009).

For the Supreme Court, therefore, Justice Chaudhry’s stint as the Chief Justice of Pakistan has been an unprecedented run in the institution’s history so far. Today, however, it comes to an end. Once Justice Chaudhry is gone, he will take all the legitimacy, independence and power he has bestowed on the Supreme Court with him. His successors will have to earn all of that all over again, albeit depending strongly on what kind of political times are there in the offing for Pakistan.

The writer is the editor of the Herald magazine.

http://www.dawn.com/in-depth/chief-justice-departs

QUOTES FROM THE COURT

Tariq Mehmood

TARIQ MEHMOOD

Former President Supreme Court Bar Association

TARIQ MEHMOOD Former President Supreme Court Bar Association

There is no doubt that he [Chief Justice] has created history. What concerns me though is that despite all the hard work he put in during the last five years, especially after his restoration, I believe he could have given more attention to matters regarding discipline. It was important to have laid a clear rule under article 184(3), commonly know as suo motu jurisdiction.

There is no denying that he [CJ] took up some serious issues on corruption but the general perception is that the CJ exercised this jurisdiction [suo motu] very liberally which resulted in some cases encroaching into [the jurisdiction of] other organs.

As a result the country’s bureaucracy was sandwiched, having on one hand to fulfil instruction by the government and being made to answer to the Supreme Court on the other. The manner in which bureaucrats and parliamentarians were consistently summoned to court was not appropriate.

Another example is the NRO case, which was declared void but all cases were remanded to the High Court. The PPP-led government did not prosecute in those cases they way they were supposed to. As president, Mr Zardari had immunity but the co-accused in the cases were acquitted. Obviously, now when he [Zardari] can be prosecuted the same evidence will be presented as they were in the cases of the co-accused. If they were not convicted then how will Zardari be?

Considering that he worked very long hours sometimes 18 to 20 hours a day, I think there was a great deal more he could have achieved but what is done is done and now part of history.

……………

Asma Jahangir

ASMA JAHANGIR

Former President Supreme Court Bar Association

Prior to his removal Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry was not a popular judge rather a crony of the executives. Everyone knew of his close links to the military and to General Musharraf and how he was elevated to the position of Chief Justice. However, after his restoration he distanced himself from the executive but he went on a vengeance which overtakes one’s sense of good judgment and justice. Matters went to the extent that he made contempt of court a weapon for protecting the judiciary even from legitimate criticism.

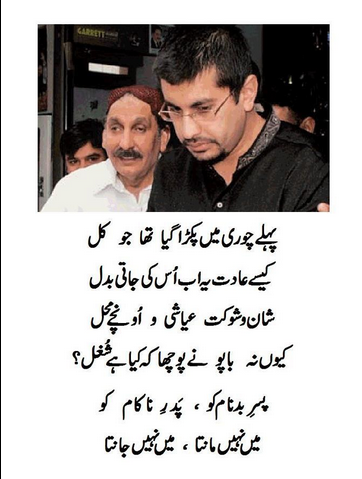

As a human right activist this [exercising contempt of court] is a severe curb on people’s freedom of expression. Especially after his son’s case he [CJ] lost all moral authority to sit on the chair and claim that he was the cleanest and mightiest person in Pakistan. The incident with his son raises questions as to how cases were selected and taken to a height with no real conclusion. In fact case management is at its worst in the Supreme Court.

His interference extended to matters of the bar council as well disregarding the bar leadership, which is why as he leaves his position there have barely been any farewells held in his honour. All the lawyers want is that suo motu cases should not be selective.

Speaking of the selection of newly appointed judges as well suffice to say that many of them have not been made on merit. Lawyers with hardly any experience of court practice are elevated and some with serious allegations of wrong doings have also made it to the bench.

Populist judges take their cue from the media that sets a very dangerous trend. Where will people go for protection then? That said, I do appreciate his initiative and judgment on some cases such as Khwaja Sera, rape victims and missing persons. But largely I think he is leaving behind a jurisprudence that is becoming more like a Jirga and will have to be corrected.

Judging Chaudhry

– by Babar Sattar

Internal differences grew with the Memogate controversy and the trigger-happy use of suo motu by CJ Chaudhry. And we saw in the last year excessive reliance on administrative powers to constitute smaller benches, pack off independent-minded judges to other cities along with inconsequential cases and reserve suo motus and other populist matters for Court One.

Both in relation to suo motu and the authority to nominate judges we saw CJ Chaudhry monopolise the collective power of the Supreme Court and the Judicial Commission, respectively. First he managed to get himself granted the exclusive right to make judicial nominations. And then in exercise of judicial power the court diminished the parliamentary committee’s role in scrutinising judicial appointments. While the Supreme Court has rightly ruled that appointments and promotions within the executive must be the product of an open, rigorous and purposive process, if the same principles are applied to judicial appointments under CJ Chaudhry, many of the appointments might not pass muster.

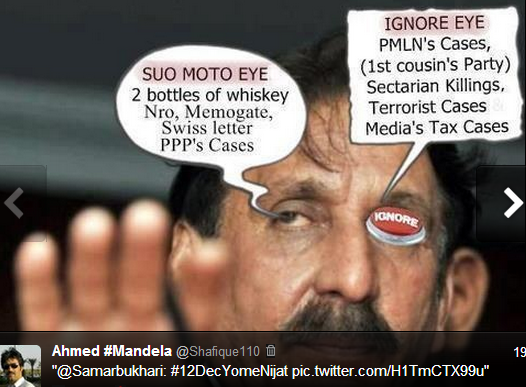

The use of suo motu by CJ Chaudhry has been problematic. Since its use rests on the will of one man, its exercise is random and inconsistent by design. For example, there is no way to understand suo motus over increase in sugar prices or recovery of two bottles of wine from someone’s luggage except as whimsical populism. Media’s role in suo motu incitement also cultivated its raunchy relationship with the CJ office that is not in accord with the judicial code of conduct.

By laying down no clear judicial tests for ‘public importance’ and ‘fundamental rights’ for Article 184(3) purposes or clarifying the nature of relief the court ought to grant, suo motu has become a source of legal uncertainty. The manner of its use denied the accused the presumption of innocence, curbed the right to appeal, and raised doubts about the court ability to act as an impartial arbiter of the law.

The use of suo motu might have cultivated in public mind the image of the chief justice as a saviour. But it has done so at the expense of our ordinary judicial system as everyone now wishes to be heard directly by our highest court. It is true that the need for suo motu arises due to a malfunctioning governance system. But it is equally the failure of ordinary judicial processes that create a need for fire brigade operations fulfilled in turn by Supreme Court’s suo motus.

CJ Chaudhry’s biggest failing is that since June 2005 he has allowed a moribund court system to limp along under his watch. Instead of throwing his weight behind rebuilding and strengthening sustainable judicial processes, he relied on suo motus to create the perception of a functional judicial system, which is nothing more than a top heavy structure suspended in mid air with moth-eaten foundations incapable of serving the judicial needs of all aggrieved Pakistanis.

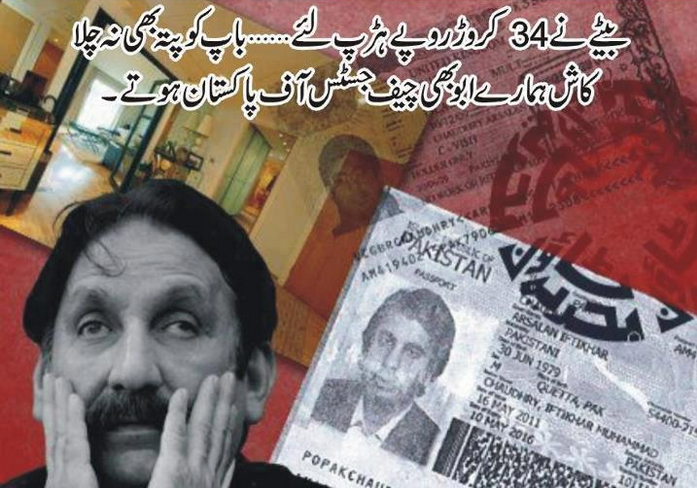

The moment of utter shame for CJ Chaudhry (and the entire court) was the Arsalan Iftikhar saga. Loud protestations of innocence did not prevent the court’s fall from grace in the pubic eye. If there was a time when CJ Chaudhry ought to have resigned to save his honour instead of showing up for work with the Holy Book in hand, it was when his son was caught red-handed.

CJ Chaudhry’s legacy is a mixed bag. He will be remembered as the politician judge who resurrected an independent judiciary, but driven by power, went too far pushing personal agendas and wading into the business of other vital state institutions. None of this should however prevent the Supreme Court Bar Association from preserving tradition and hosting a farewell dinner for the outgoing chief justice even if not for the man.

The writer is a lawyer.

sattar@post.harvard.edu

http://www.dawn.com/in-depth/chief-justice-departs

25. I was suggested this web site by way of my cousin. I am now not positive whether this post is written via him as no one else know such unique approximately my trouble. You are amazing! Thanks!

chanel wristlet replica http://www.qprdot.org/?P_view=6193