Pro-Taliban narrative has been prevailing in Pakistan, mostly out of the fear of Taliban attacks or due to influence of ‘Deobandi’ and ‘Tableeghi’ schools of thought – Shafqat Munir

The year 2014 claimed lives of over 4,065 people in conflict and terrorism related incidents in Pakistan, including the worst ever terrorist attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar on December 16.

This incident happened to be the 9/11 of Pakistan that brought the whole nation on one page, from the military to the political establishments all are talking about rising beyond ‘good Taliban, bad Taliban’ division. Even Imran Khan, who has been opposing the military operations against Taliban saying it was not ‘war of Pakistan’ but a ‘war of the United States,’ had to rethink and end his anti-government movement to express solidarity with the army, government and the people of Pakistan in general, and the families of the children martyred in the December 16 incident in particular.

The people of Pakistan from across all divides and shades came to the streets, demanding stern action against terrorists who are on a killing spree. It seems that the Taliban fear factor is diminishing and civil society and political parties and the prime minister himself are talking about action against terrorists and their abettors and supports. The government is devising a counter-terrorism strategy to combat the menace and to regain its writ in various cities and the bordering areas from where Taliban are continuing with their sporadic terrorist activities.

Despite the fact that the army and the government with almost all stakeholders on board are busy taking some serious actions, people apprehend that this spirit might be diluted with the passage of time as they believe that only cosmetic actions may not be helpful. Since the issue is not just fighting terrorists or Taliban who are killing people in the name of Islam, there is a need to fight against the growing narrative of religious fanaticism and radicalism supporting the Taliban narrative in the country.

Unfortunately, media discourses on select media outlets and ‘Tableeghi’ (preaching) approaches in and outside madrassas have been instrumental in spreading the extremist narrative in the name of Islam. The abettors and supporters of Taliban’s narrative are found everywhere — in villages, towns, government offices, media houses, military and political establishments. First of all, we have to fight this narrative that spreads hatred and extremist thoughts and fans intolerance in accepting others’ point of view and uses ‘gun’ to impose their religious thoughts on all and sundry. This sort of militancy needs to be tackled seriously with a commitment that this ‘war is our war and not of others’ if we are really serious to ensure that terrorists cannot kill our people.

Unfortunately, pro-Taliban narrative has been prevailing in Pakistan, mostly out of the fear of Taliban attacks or due to influence of ‘Deobandi’ and ‘Tableeghi’ schools of thought. The 2013 election campaign was dominated by the Taliban factor as they had openly said they would not attack rallies of Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz), Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaaf (Imran Khan led-PTI) and Jamaat Islami and some other right wing parties. Taliban had categorically stated that they would not allow Pakistan People’s Party (Zardari-led), Awami National Party (Asfandyar Wali-led), Mutahida Qaumi Moverment (Altaf-led) and other liberal democratic parties to run their election campaigns.

PML-N, PTI and religious parties openly campaigned and returned to parliament. Jamaat Islami and PTI formed coalition government in Khyber Phukhtoonkhwa. Imran Khan, throughout the last decade, did right wing politics and claimed that ‘war on terror’ was a ‘US war’ and not ‘Pakistan’s war.’

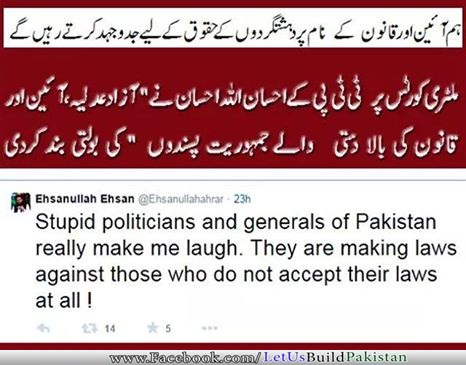

Imran’s, and similar narratives, somehow confused their supporters and caused a division in the nation, which had seemed to be on the same page against the terrorists after the school incident. Even when the government at the level of prime minister is expressing resolve to fight back with no pick and choose between ‘bad and good Taliban,’ civil society is critical of inaction by the government against abettors of Taliban who are still openly expressing support for them and have not condemned the attack on the school. A key pro-Taliban cleric and imam of the central government controlled mosque in Islamabad, Maulana Abdul Aziz, has refused to condemn the attack; he rather supported Taliban saying he subscribed to their ideology. Since he had made an open statement, civil society and political parties are calling for his arrest. Despite lodging of cases against this Maulana, the government is still reluctant to arrest him. Even the government, ruling Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz), and PTI are silent on this issue.

Media is divided on the narrative as some media outlets are covering the nation’s anger against terrorists while some are still confused about ‘whose war is this’ question. Analysts, who have a close eye on those who set media’s agenda in Pakistan and who actually give direction to national narrative building through media discourse, believe that there is still a huge gap between words and actions. The forces who are providing protection to pro-Taliban clerics such as Maulana Aziz still think that retrogressive agenda of ‘narrow religious interpretations’ helps them to threaten pro-democracy and liberal elements of charging them under blasphemy law. They say some segments in military and political establishment do not want to expose all of their retrogressive cards. So, they want the narrative to remain confused.

The situation in Pakistan is really bad and requires stern and immediate actions with long-term policy options. There is a dire need for military and political establishments to decide once for all that retrogressive narrative that gives space to religious extremism or Talibanisation needs to be de-radicalised through curbing hate speech and literature. Media should be given clear agenda of peace and tolerance, madrassa should be brought under control of authority as are other schools and colleges. Mosque imams should be given a vetted khutiba (speech) for Friday sermon, as is done in Saudi Arabia. The military courts would only partially address the issue by pushing terrorists after summary trials. But this may not provide a solution until we sincerely fight against the religious extremist narrative that ultimately provides fuel to Taliban. Above all, the government, military establishment, media and civil society should build a new narrative of a peaceful, enlightened, moderate democratic Pakistan replacing pro-Taliban narrative that is prevailing in the country through a network of religious seminaries of a hardliner’s school of thought (Deobandi). Pakistan cannot give more children to terrorists to kill. Enough is enough, if still we keep on confusing the narrative, we will plunge further into a deeper trap of terrorism. Pakistan needs to analyse how best it can live in peace without compromising security of its people and territory.

Source:

http://www.thedailystar.net/countering-terrorism-need-to-change-pro-taliban-narrative-58604