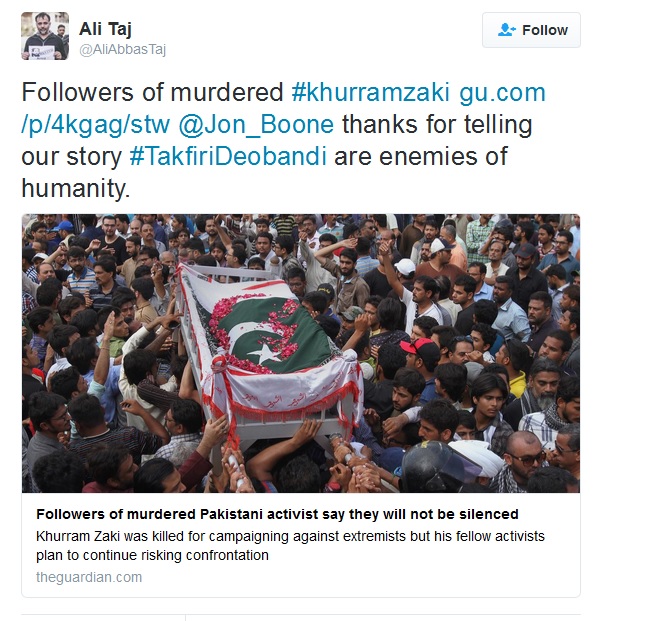

Followers of murdered Pakistani activist say they will not be silenced

The followers of a Pakistani rights activist murdered for his daring campaigns against extremists say they are determined to continue risking open confrontation with some of the country’s most feared Islamist and sectarian groups.

Khurram Zaki was shot dead by unknown gunmen on a motorbike on 7 May while eating with fellow activists at a restaurant in Karachi.

Even some of his admirers thought he had been reckless for trying to lodge criminal charges against feared clerics, including Abdul Aziz, the leader of Islamabad’s infamous Red Mosque, an extremist base in the capital.

A Pakistani Taliban faction later said it killed Zaki because of his efforts to lodge a criminal case against Aziz, which Islamabad’s police had refused to do.

Jazib Qamar, a Karachi student who was also shot and seriously injured in the attack, said he had not been deterred by the death of his friend.

“We have no choice but to keep fighting,” Qamar said. “The army or the state can’t save us. Until the common man stands up against terrorism nothing will change.”

Khalid Rao, another Zaki ally who was injured during the shooting, has fallen into a deep depression. Friends say he spends days sitting at the Karachi market where Zaki was killed.

The activist’s murder triggered international condemnation but, at least among some of Zaki’s associates, little surprise. They had long feared it might happen.

In the past they had joked about registering a criminal case against the country’s most infamous sectarian clerics when Zaki was killed – which they did, lodging a police first investigation report against both Aziz and Aurangzeb Farooqi, the head of Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ), a banned Sunni supremacist group.

Zaki made a habit of not just challenging Islamist extremists online through the website he co-edited but also physically confronting extremist groups, even bringing his young children to one vigil outside an ASWJ gathering in Karachi.

“People used to say he was suicidal because he was openly condemning banned outfits,” said Syed Talib Abbas Raza, a university lecturer. “No one else was prepared to protest in these places.”

Raza and other friends of Zaki have continued to try to force the police to take action against preachers who flout the country’s anti-extremism laws, including those brought in after the December 2014 Taliban massacre of more than 130 schoolboys in Peshawar.

“It’s our job to put pressure on law enforcers to enforce law in their jurisdiction,” said Musaiyab Ghazi, who was among a small group of activists who last month forced police to prevent Farooqi from addressing ASWJ rallies.

“The rest of the human rights community in Pakistan don’t disagree with us but they don’t come out on the ground to confront these people,” Ghazi said. “You need to take risks in order to expose these people.”

But they all admit there are perhaps just a few dozen people in the country prepared to run the risks they are taking.

In Bangladesh, more than a dozen liberal bloggers and activists have been killed in recent years, but Pakistan has not experienced a similar number of attacks.

For one thing Pakistan, unlike Bangladesh, does not have any outspoken atheists prepared to campaign for their opinions in public.

But those who challenge the country’s drift toward radicalisation do appear to be at risk. In April 2015, Sabeen Mahmud, a Karachi-based liberal campaigner, was killed outside her arts venue.

Saad Aziz, one of the men arrested, reportedly told police he had targeted her for protesting against efforts to ban Valentine’s Day, a western tradition particularly hated by the religious right.

In 2014, Raza Rumi, a journalist who had been outspoken in his criticism of militant groups, was forced to flee the country after gunmen attacked his car in Lahore, sparing him but killing his driver.

In a video released in May the leader of al-Qaida’s South Asian franchise claimed the organisation was targeting its ideological enemies in both Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Zaki was a particularly controversial character for many on Pakistan’s religious right because he and several of his followers had been brought up within the Deobandi movement, the school of Sunni Islam which the Taliban and the majority of the country’s militant groups adhere to.

Not only did he reject the Deobandi teachings, he also converted to Shi’ism, the Islamic sect especially despised by many of the country’s most virulent Sunni groups.

Zaki and his supporters never missed a chance to lambast what they called “takfiri Deobandi militants”, a sharp criticism of the extremist practice of terming opponents “takfir” or unbeliever.

“Zaki’s tragic martyrdom has been an incalculable loss to all progressive and peace-loving Pakistanis,” said Ali Taj, the US-based editor of Let Us Build Pakistan, the spiky website Zaki helped run.

“He not only challenged terrorists, he also called on senior Deobandi clergy to either clearly and unconditionally disown and condemn them or be ready to face criticism.”

Source: