The twin pillars of PPP

On April 4, a day with flowers in full bloom, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) of Pakistan was led to the gallows. He was 51.

Not far from the site which ended his life, his daughter, Benazir Bhutto (BB) was assassinated some 28 years later, age 54.

Both had already made their mark in the politics of Pakistan while still in their twenties. But the sunset came too soon.

How did their lives and their end impact Pakistan? And the PPP? Great political movements often embody the personalities of their protagonists. To get a sense of what the PPP is all about, one has to plumb into the personality and characteristics of its creator who carved the party in his own image. And his daughter who carried the flag and remoulded the party to reflect her own style.

An anniversary is a good time to recollect and recapitulate. I happen to be among the very few living to tell the story. So here I am. I decided to take the memory walk and re-live their lives through my eyes ─ before the story fades into the haze of myth.

A naya Pakistan

ZAB had announced himself on international stage as Pakistan’s youthful foreign minister and became a war hero through his spell binding oratory at the United Nations (UN) and his defiance as manifested at Tashkent.

He had become the darling of the youth who flocked to the Lahore railway station to catch a glimpse as he made his way back home after resigning from Ayub Khan’s cabinet in March 1966. It was a defining moment in Pakistan’s history.

ZAB’s arrival on the big stage coincided with the iconic 60’s.

Those were the days when the world around us was changing. There was nothing subtle or gradual about the change, it was almost as though a powder keg of ideas catalysed, bringing forth an ideological and lifestyle revolution, one that shook establishments the world over.

The hippy movement, Bob Dylan and the Beatles, the flower power and Woodstock went side by side the anti-Vietnam war student marches in the United States (US), the student rebellion in France, the non-aligned movement of the Third World. Cassius Clay, the Palestinian freedom fighter Leila Khalid, Martin Luther King and of course the Kennedy brothers (JFK and RFK) captivated hearts and minds. And then there was the super iconic Che Guevara whose very image thrilled the young like a surge of electricity. Those were heady days indeed, epochal in many ways.

World leaders like Nkrumah, Nasser, Tito, Ben Bella, Mao, Chou en Lai and Soekarno stood tall on the world stage. And ZAB stood alongside them. They had become his personal friends.

As a young Grammarian with Marxist tendencies I was not immune from the whirlwind of events taking place around me.

I had always, as a kid, hero-worshipped my uncle, but now that he had picked up the banner of defiance and set out to smash the holy grail of set conventions and embedded ideas, I was a devotee. “Oh to be young in that dawn was very heaven.”

When ZAB formed the PPP in Lahore, I made the train journey to be at Dr Mubasshir Hassan’s home.

A charged and enthusiastic crowd of supporters had gathered to usher in a new dawn, the birth of a Naya Pakistan. The party’s Teflon-like manifesto, hard hitting with catchy slogans, spread like forest fire. And then began the march!

ZAB toured the country like hurricane tearing through land. No city or town, no village of hamlet was overlooked. As a devotee, I skipped school whenever I could manage to join the ZAB road show.

What struck me was his easy connection with the masses. He had both an aristocratic bearing and the common touch.

He would speak to crowds ─ the shelter-less and the shirtless ─ in vernacular Urdu, the common man’s language in an idiom they readily recognised.

He was hard wired into the lives of ordinary people and their daily concerns, his finger always on their pulse. There was magic in the way he spoke, in the manner he moved. The poor and the young alike idolised him. ZAB had broken conventions and demolished cherished myths.

His rallies were attended by the poorest of the poor who came to him because he symbolised their dreams and their hopes.

There were none of the Defence Housing Authority and Cantonment begums with designer hand-bags and shades. That, after all, was the class he was hitting at.

Everyman’s man

ZAB had a photographic memory and never forgot a face or a name. Once driving with him through the dusty tracks of Sindh, I observed that crowds gathered at every corner and bend to see him. The car would stop and ZAB would shake hands and exchange a few words, always asking the name of the man he shook hands with.

One young man stuck out a note pad and asked for an autograph. ZAB duly obliged. Much later, on the way back to Larkana ─ it was now late and dark and again ─ the car pulled up to greet the people gathered around.

A young man stuck out a note pad for an autograph. “But Muhammad Ramzan, I have already done this for you this morning,” retorted ZAB. The man looked as though he had seen a ghost.

ZAB was always comfortable with the poor in their huts, squatting with them, sharing bread and a cup of tea. Many a time, wearing his Saville Row suit, he did not shirk from the sweat and dirt on the torn and tattered clothes worn by peasants and labourers as he hugged them.

ZAB possessed a vital magnetism which he transmitted to the people. He could touch the raw, emotional well-springs of the nation. He knew their pulse, their heart beat. They laughed and cried with him. There was a compelling chemistry, an electrical charge that has not dulled with time. It was, in his own words, his greatest romance.

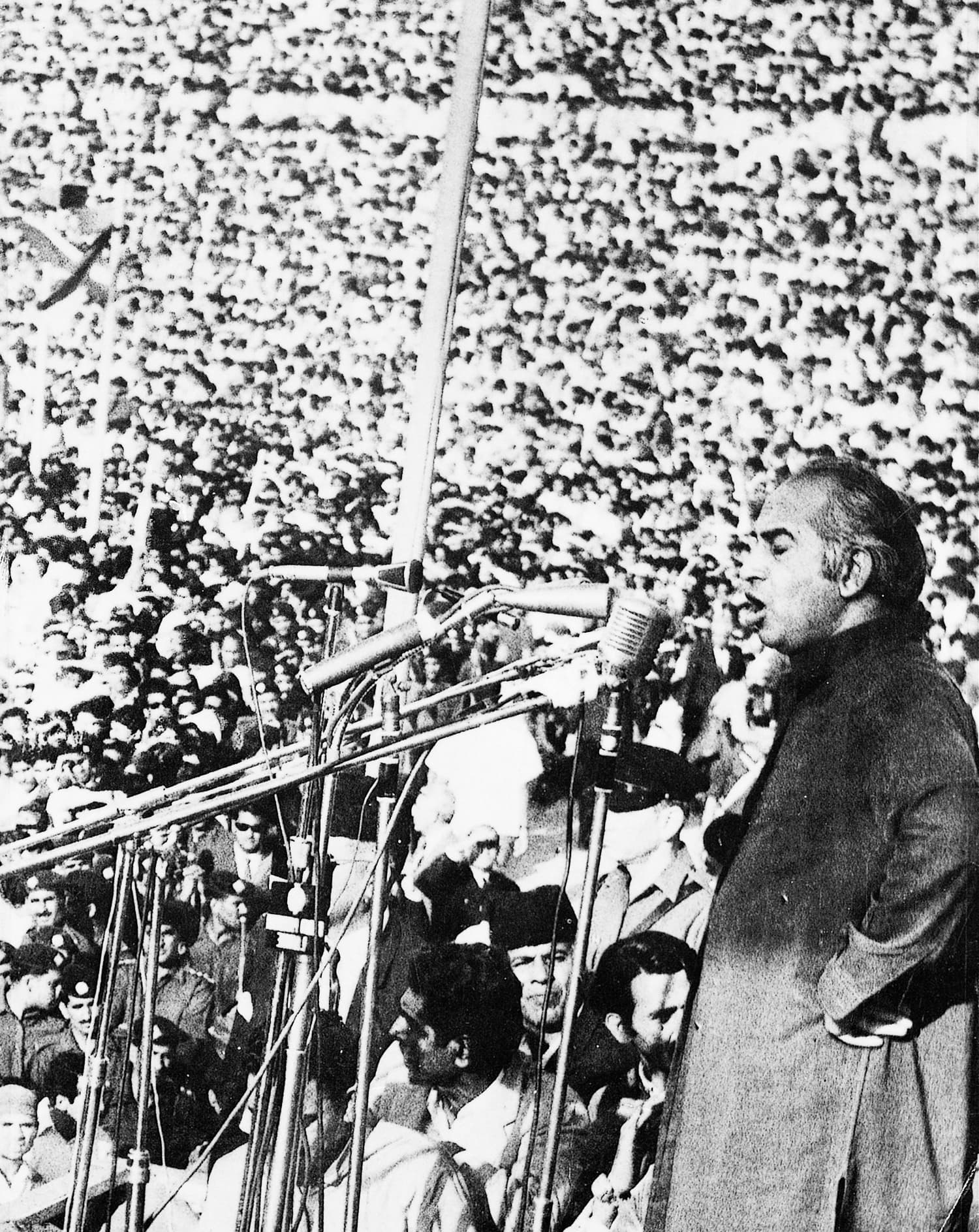

ZAB addressing a crowd.

He gave to the poor a future and he gave them a voice. He gave them consciousness and dignity. That bond has been frozen into doctrine.

ZAB was a complex individual, beset with contradictions.

He was equally at ease at the Queen’s dinner table as he was squatting on the rugged floors of the poor in their huts. He was western and eastern in equal measure. As he said to Oriana Fallaci “My mind is western but my soul eastern.”

He could speak at an international or intellectual forum with the same command as when addressing the masses at Mochi gate.

ZAB was a man in a hurry. He was always conscious of the fact that the Bhuttos’ die young and suffered from a premonition about his own early end. So he moved at break-neck speed.

His detractors, as they are wont to, point at his personal flaws and shortcomings and comment frequently on the “dark side of his nature”. Perhaps the words of Thomas Wolfe lend some context here: “Dark time that haunts us with the briefness of our days.”

But his achievements were real. When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto took the reins of a truncated Pakistan in December 1971, a new state was taking shape, not, as in the case of Bangladesh, through the euphoria of liberty but through the trauma of decapitation and dismemberment.

Unlike 1947, this was not the dawn of hopes and aspirations, only distress and dejection. In 1947, Pakistan had to be built from the physical building blocks. In 1971, it had to be rebuilt psychologically.

ZAB gave Pakistan an enduring industrial infrastructure. He gave the country the 1973 Constitution which remains its load star even today. His crowning glory of course was the nuclear programme, for which he paid with his life and suffered a “horrible example” as promised by Henry Kissinger. He nursed back to health and rebuilt the morale of a defeated and dismembered country.

Pakistan was diplomatically isolated in the world. He crafted a place for it on the international stage. He broke Pakistan’s cramped obsession with India and carved a separate identity for his country which no longer was viewed from the sub-continental prism.

He united the Muslim world under his chairmanship at the Islamic Summit Conference held in Lahore. His masterful diplomacy at Simla drew parallels with the brilliance of Metternich and Talleyrand.

His vision was to form a third world club to carve out an independence from the western economic yoke and to free itself from exploitation through supply of cheap labour and raw material.

He wrote a political treatise entitled “Third World ─ new directions” in which he propounded his ideas. His ideas sent alarm bells across the Western world, which viewed his continued presence as a threat to their political and economic agenda.

They also did not overlook his speech at the Islamic Summit Conference, when he thundered: “What is this even-handed approach they talk about? Are the Arabs the aggressors or is Israel the aggressor? The soldiers of Pakistan are the soldiers of Islam. We shall never rest till we regain every inch of Palestinian territory.”

And so he signed his own death warrant.

ZAB’s time as head of government remained untainted by the moral squalor or charges of corruption.

Indeed General Ziaul Huq unsuccessfully turned heaven and earth to find some shred of evidence. Given the social and moral mores of the times we live in, this in itself is a profound statement.

ZAB is often accused of arrogance. His arrogance was reserved for a certain class, his own.

My grandmother came from a less privileged background and struggled to find acceptance in the feudal and aristocratic Bhutto family, which surely rankled him.

He internalised his wrath which perhaps manifested through a certain antagonism against his own class.

As children, when my mother and her siblings visited Larkana, my grandmother would clandestinely take her children through the narrow, dusty lanes of the town to call upon the less privileged.

They witnessed the lives and conditions of the less-advantaged first-hand. There was a strange inner conflict and contradiction born from having parents from such opposite scales of society. They admired their father for his political power and aristocratic bearing and loved their mother for her humility and kindness.

ZAB would move easily among the poor and embrace them, sweat, dirt, et all. He could take their criticism and ranting with good humour and often wept with them.

Certain folks looked askance and wondered whether this was an act. It was never an act! ZAB remained resentful and suspicious of the elite and upper classes and did little to mask his antipathy.

His own cerebral qualities were unmatched by his peers and he, in turn, was contemptuous of the pseudo-intellectuals among them.

The drawing room and the “intellectual” classes duly returned the compliment. Neither time nor tribulation has diminished their visceral hatred.

The triumphs and trials of the Bhuttos

Growing up around the Bhuttos was both fun and traumatic. Conversation in the Bhutto house was a fierce and competitive sport, a gladiatorial contest. You had to defend your airspace with volume and fluency. No quarter was given and zero tolerance accorded for being in the intellectual shallow end. Say something lightweight and you ran the risk of being condemned as spectacularly stupid. The fight was always on to score intellectual points and show off superior knowledge of history and politics, descending the next moment to a ferocious brawl over a bottle of tomato ketchup. The sublime and the ridiculous coexisted with consummate ease in the Bhutto household.

My cousin Murtaza (Mir) was a close friend of Robert Kennedy (Jr). Bobby came to London in 1975 to read politics at the London School of Economics and we spent a fair amount of time together. I was struck by the striking similarities between the Bhuttos and the Kennedys. Above all was their indomitable will, spirit and fearlessness.

ZAB with his children, Mir (L) and Benazir (R).

Benazir was brilliant, levels above ordinary mortals. She had a warm, human touch and doted upon her friends. There were the Waheed sisters, Samya and Salma, the Punthaky sisters, Feroza and Paree and Yasmin (with whom she arranged my match while in exile in London).

She remained fiercely loyal to them all through the many twists and turns of her life. She often called them her Charlie’s Angels.

Through the triumphs and trials of her life, BB saw more pain than was her fair share. Fate dealt her a cruel hand.

She fought like a tigress for her father’s life and counted on her beads as she waited for the moment to pass.

She was never permitted to see her father’s body to say her final farewell. She underwent long periods of confinement and jail. While at Sukkur Jail during the oppressively hot Sindh summer, she was kept in appalling conditions and suffered permanent damage to her left ear.

She witnessed the untimely death of her brother, Shahnawaz (Shah), in Cannes in the French Riveria, who fell victim to a sordid conspiracy. He was 27.

Myths, like mettle, are frequently recycled, and the lingering miasma of toxin born of jealousy follows the Bhuttos.

Many stories and scandals were spun around this tragedy.

I was in Cannes that summer and had left only a week before Shah’s murder. What I witnessed was a perfectly happy family.

Many years later when I accompanied BB in the summer of 1989 on her visit to Paris to attend the Bastille Day bicentennial celebrations, Mir also travelled from Damascus along with his daughter Fatima to join us.

A retired French police officer who had originally investigated the case came to see Mir at the Ritz Hotel where we were staying. Mir asked me to join in. What the officer revealed was alarming.

He recounted how he was summarily removed from his role when he closed in on the murder case and discovered that Shah’s wife, Rehana, had been used as a tool in a dark and unholy conspiracy.

Knowing what I know, I find it painful when some senior and seasoned stalwarts of society distort facts and add their own toxic mix to a cocktail of lies and slander. Or at best just tap dance around the truth.

BB performed her duty to her country and her family with equal passion and carried Shah’s body back to Ghadi Khuda Bux.

Years later, during her term as prime minister, her brother, Mir, was shot in cold blood, just yards away from her father’s home at 70 Clifton at the age of 42.

I accompanied her to Mideast Hospital where Mir lay in a pool of blood. She broke down and collapsed in a paroxysm of pained hysteria. Mir’s death was the defining moment in the tragedies of her life.

Like a Shakespearian tragedy with an Orwellian twist, the drama of death was draped in irony. That the doubters, of whom God knows were aplenty, scoffed at her tears, which deeply hurt her.

Mir’s death hung like a lingering splinter in her mind. And while Mir slept peacefully, she was confronted by the dark nights of the soul.

His memories, like a montage, were framed in her mind, which neither time nor travail paled. She knew of my closeness to Mir and often, in tear-soaked eyes, talked of him.

Her epic struggle against the dictator bore fruit and she became the youngest woman to head an Islamic country when she became prime minister at the age of 36.

For a brief shining moment, the world was hers and a brilliant star blazed over her horizon — then the moment passed. And night closed in again.

Her brief spell in government was cluttered with byzantine-like intrigues, which can be best captured by paraphrasing a passage from T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom: “The morning freshness of the world-to-be intoxicated us. We were wrought up with ideas inexpressible and vaporous, but to be fought for. We lived many lives in those whirling campaigns, never sparing ourselves: yet when we achieved and the new world dawned, the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew.”

Bravely, she struggled and went on to become PM for the second time. But tragedy was written in the stars.

Her government was dismissed by her hand-picked president. During her political journey she encountered many “friends and supporters” who were strangers to loyalty’s realm.

She desperately sought loyalty and trust in a jungle of faithlessness. With her mystique and sedate glamour, she was forever sliding through time and space.

Of all the tragedies in her life, perhaps the saddest was that she was deprived of the joys of youth. She never had the luxury to be young, although she yearned for all that the young dream of.

Her happiest days were in college at Radcliffe and then at Oxford. These were carefree, halcyon days but her dinner company was always eclectic, ranging from fellow students to professors and academics.

BB lived on a very tight budget during her London exile years, which perhaps caused in her a sort of financial bulimia. She was loathe to spend money she considered wasteful.

Much later, in her second exile during the Musharaff era, she would spend the summers in London with her children. She kept them tight too, taking them to the low-end Primark or M&S for shopping.

She told me once that they complained bitterly about their simpler apparel as all their friends and peers in the Choueifat School in Dubai came from elite families and donned designer jeans and expensive accessories.

BB pictured with Margaret Thatcher.

When I empathised with their misery, she became genuinely angry and harangued me on the importance of imparting proper values to children. “They must learn the value of money, especially when they come from a poor country like Pakistan,” she would say.

BB was painfully frugal when it came to her own material needs. Although she could afford most things, she would shrink from the high price tag of designer handbags and accessories.

She would regularly organise family outings, which mostly consisted of going to the Bayswater bowling centre or to dinner at her favourite pad, Mario’s in Kensington, for some low-priced pizzas.

Looking back at her life, it has been both tragedy and triumph. It was a roller coaster ride of highs and lows. It touched the sublime and entered emptiness. She became both a person and a metaphor.

People often make comparisons between father and daughter, which is unfair and at best can be tenuous.

They lived in different times. ZAB belonged to an era of passion and poetry, an era of rage and revolutions.

BB’s arrival coincided with an era which witnessed the retreat of ideology and collapse of the old world order.

Asia was no longer red and the warmth of ideological idealism had given way to the coldness of economics and Gross Domestic Product. Politics was no longer poetry.

Benazir was always conscious of the inevitable comparisons and struggled to bridge the gap. They were both brilliant and tireless. Both had untapped reserves of energy and vitality. Both had a formidable aura. Both were populists and had the common touch. Both father and daughter turned the word Bhutto into a brand name… A national political web site for Pakistan.

For BB, the entry into Politics was an act of force majeure. Freshly returned from Oxford, where she had been the President of the Students Society, like any other youngster she had her own dreams. Fate placed her in the driver’s seat and she learnt to drive quickly. She had an outstanding tutor who taught her the ropes from behind his iron bars.

ZAB was always a tough act to follow and it goes to her credit that she alone could even seek to don that giant mantle.

If ZAB’s populist style set a template for Pakistan’s future political culture, Benazir was a perfect fit for that template. ZAB arrived on the stage as a national saviour in the aftermath of Pakistan’s humiliating defeat and dismemberment. From the shadows of Zia’s eleven year period of drab and joyless existence, BB came in to fill the vacuum of spirit and style.

Both father and daughter were completely fearless. ZAB stood out like a gladiator during a violent attack on his procession in Sanghar in 1967. As shots fired by the Hurs rang past his ears, he stood up to shield his workers, pointing to his chest and asking his assassins to shoot at him instead.

On another occasion, along with Mir and Shahnawaz, I was with him atop a truck when he was leading a triumphant procession through the streets of Larkana following his release from house arrest 1968. Suddenly a man appeared in front of the truck and pointed his pistol directly at ZAB. He did not flinch. The man was fortunately overpowered in the nick of time and disarmed.

BB arrived in Pakistan on October 18, 2007, against all advice. There was a huge crowd to receive her at Karachi airport. A few hours after the procession was still making its way forward at snail’s pace, a deadly bomb attack ripped apart her truck and over a hundred of her jiyalas lay dead around the vehicle. Her concern was for those who had died or been wounded, never for herself.

The very next day, without any security or escort, she drove straight to Lyari to visit those who were in hospital and condoled with the families of those who had died. Neither threats nor warnings deterred her as she valiantly cut her path across Pakistan’s towns and cities, frequently standing up on her four-wheeler and exposing herself to danger.

Indeed, on the fateful December day she was assassinated, she had received a warning from a highly credible source about an impending attempt on her life. Being the brave daughter of a brave father, she did not retreat. She marched to her death.

That Pakistan today has a nuclear umbrella, it has to thank both ZAB and BB. The father gave Pakistan a nuclear capability and the daughter risked her life in providing her country with missiles and a credible delivery system.

Mortal, immortal

In March 1979, Mir asked me to travel to Rawalpindi to meet ZAB. He wanted me to get the trial and some other documents back for a conference of International Jurists organised in London, presided by the former Us Attorney General, Ramsey Clarke.

More importantly, he wanted me to convey two critical messages to ZAB. The Afghan government, then under Babrak Karmal, had offered Mir a base in Afghanistan. Second was a personal message from Yasser Arafat which was time-sensitive.

Yasser Arafat had asked to convey to “my brother Ali Bhutto that he was an asset for the Islamic world and regarded as a hero by the Palestinian people. PLO was ready an operation to spring him from jail and out of Pakistan.”

I travelled to Rawalpindi and on March 27 had my first meeting with ZAB. As I was being escorted along the long walk from the entrance to my uncle’s cell, the jail superintendent Yar Mohammad related an anecdote.

He told me that the cell attendants from the police were constantly shuffled so as not to get too attached to the former premier. He then recounted how one such attendant happened to be a constable on duty when Bhutto was PM.

While leaving the Sihala rest house in the late hours of the night, after concluding his negotiations with the PNA leaders who were under protective custody, ZAB paused just long enough to express his regret that the constable had to perform his duties at such ungodly hours and asked him about himself and his family.

This was way back in June 1977. Now, two years later, the constable appeared before ZAB in his death cell and without a moment’s hesitation, Bhutto referred to him by his name and asked about his children individually by name. The man felt duly shattered. This was the best example of the famed photographic memory which had won hearts and minds across the length and breadth of Pakistan.

As I arrived at the gate of the death cell, I was horrified at what I saw. The cell was barely six feet by twelve and had a slim mattress on the floor. What I saw was a ghost of a figure who was so thin and gaunt that I was reminded of the Nazi prisons from the World War II films.

My uncle was quick to observe my shocked disbelief and tried immediately to put me at ease by saying “Tariq, I have to compliment you on how you are dressed.”

Spontaneously, I responded “Sir, when you come to visit the Prime Minister of the country, you have to be dressed as such.” He broke in to a broad grin.

As I was not allowed in, we spoke in whispers from across the cell bars, closely observed by intelligence men trying to eavesdrop on the conversation. I conveyed the two messages.

To Mir’s request to relocate to Afghanistan, the response was a quick and furious NO. “I did not send him to be educated at Harvard and Oxford to become a guerrilla fighter. I absolutely forbid him from going to Afghanistan.”

For the second message, he responded “Tell my brother Yasser Arafat that I thank him from the bottom of my heart, but come what may, I will not leave Pakistan. This is my country. This is where I will die.”

We talked about various other things and then he asked, “You are coming in from England. What is the press there saying about me?”

Assuming naturally that he was enquiring about their reports on the murder trial, I responded “They all maintain that you are innocent and this has been a kangaroo trial.”

Furiously nodding his head with acute exasperation, he retorted “No, no you fool, I don’t care about this trial. Everyone knows of my innocence. What do they say about my brains, my stature as a statesman?”

I could not believe that here was a man only yards away from the gallows, whose concern was not for his life but how history would record him. Not once did he express concern about his fate. He became philosophical and with remarkable prescience, said “After I am dead, they will write songs and poems about me, I will pass in to legend.”

A few weeks prior to my meeting, Dr Zafar Niazi (later to become my father-in-law) who was ZAB’s dentist, attended to him at his cell as he was suffering from an acute gum infection. When Dr Niazi saw his condition, he expressed his concern.

“Don’t waste time, doctor, we have more important things to talk about. I know I can trust you, so here are two things I need you to do as soon as you leave this place. I want you to go straight to Dr AQ Khan and convey that under no circumstances must Pakistan’s nuclear programme be derailed. Second I want you to go to the relevant people with my message that the Karakoram Highway, which I fast-tracked, must proceed as planned.”

Dr Niazi was dumbstruck and turned from a supporter to a diehard. The first thing he did when he reached home was to gather his family around him to warn them of the difficult times ahead, as he planned to openly canvas diplomats and the world leaders to draw their attention to Mr Bhutto’s plight.

Indeed, not only Dr Niazi but his wife and daughters were sent to prison and Yasmin eventually had to flee to exile, when they came to arrest them a second time.

Dawn broke on April 4, 1979, snuffing out a life but kindling a legend.

ZAB’s body lay waste as millions of his jiyalas silently mourned. I could not help thinking back to the time when, as a spunky 15 year old, I had been there in Lahore when the candle was first lit. We had come to the end of a journey.

Long after they have passed, BB and ZAB, like Colossus continue to dominate the political landscape of Pakistan.

Their deaths have nourished an enduring legend. ZAB went to the gallows, defiant to the end. BB, caught in the whirlpool of overlapping loyalties and conflicts, succumbed to a carefully crafted conspiracy.

She knew she was walking the death road but the lady was not for turning. Both died as the Mexican revolutionary Zapata had idealised: “It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees.”

The soil on their graves has crystallised into a shrine. People flock there to seek relief and redemption. Many claim to have their prayers answered. Long after the maestro and the conductor have gone, the symphony is still heard.

PPP is the party of spilt blood. It is as much a passion play as it is a political party. One is persuaded to recall the touching words of Elton John’s eulogy “Candle in the wind” to Princess Diana: “Never fading with the sunset, even when the rain set in, your candles burnt out long before your legend ever did.”

ZAB and BB, the twin towers of the PPP rest in the hearts of the people, from whence they cannot be removed. Where will their party go from here?

From his death cell, ZAB had counselled his daughter in an epic letter on the occasion of her 25th birthday: “Heaven lies at your mother’s feet. Politics lies at the feet of the people.”

The PPP is too organic and too deep-in-the-soul a party to simply vanish or sink into the permanent abyss of darkness. For it to regain its former glory, a flower must bloom when it is not spring.

Source:

http://www.dawn.com/news/1249503