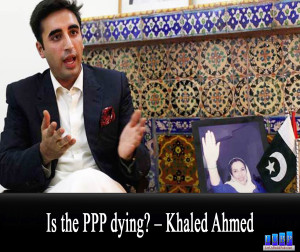

Is the PPP dying? – Khaled Ahmed

Pakistan’s only “federal” political party, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), suffered a blow to its solar plexus when Asim Hussain was arrested in Karachi for corruption on August 26. An old schoolfellow of and personal physician to PPP boss Asif Ali Zardari, Hussain was federal petroleum minister in the PPP government till 2013. Currently in charge of higher education in Sindh under the provincial PPP government, he is rumoured to be involved in big-time land grabs in Karachi, in addition to some shady deals as petroleum minister. Ominously, August was also the month when Zardari decided to fade into the background and anointed his son Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari as the new party leader.

In Karachi, in front of a crowd at the family’s residence — Bilawal House — Bilawal said: “I want to tell those living in a fool’s paradise that the PPP is not over, neither will it be finished. It will rather flourish because after Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his daughter Benazir Bhutto, I will now lead it by hoisting its flag.”

The summer of 2015 has been tough for the PPP. Defections began in Punjab among party men miffed with the way the party headquarters in Karachi was doing national politics and running its internal hierarchy. The biggest province, Punjab, with more seats in its assembly than the federal National Assembly, has only six PPP representatives as opposed to 214 belonging to the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN).

The PPP rose as the supreme party of Pakistan after the 1970 election. It also swept Punjab and gained a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly. Its presence in all four provinces had marked it as the only “federal” party. This status was retained from 1988 onwards till, in 2013, its defeat in Punjab made it lose that distinction. The adage in Pakistan is, if you are absent in Punjab you are out of politics.

The counter-adage — if you are absent in Pakistan but present in Punjab, you still count for something — was proved by the PMLN, which has dominated the largest province since 1990, remaining more or less absent in other provinces while ruling Pakistan from Islamabad.

Christophe Jaffrelot, in his latest book, The Pakistan Paradox (2015), thinks the PPP started flaking ideologically the day it was founded. In fact, the flaking part engaged the common man far longer than it deserved and the pragmatic backsliding of its leaders eased its journey of survival. It attracts the liberal-secularist even today despite this obfuscation.

The founding charter of the party in 1967 said: “The ultimate objective of the party’s policy is the attainment of a classless society which is only possible through socialism in our times.” If truth be told, the party was always more populist than socialist. In 1970, it was already inducting ex-PML feudal landlords into its fold. It nationalised the economy in 1972 and promised roti, kapda and makaan, presumably free of cost, to its followers.

Its socialism became “Islamic” soon enough, which was further emphasised with the second amendment excommunicating the Ahmadi community as non-Muslims. As nationalisation led to economic collapse, the seeds of the party’s death were quickly sown. Zulfikar was hanged in 1979. The long military rule under General Zia-ul-Haq that followed was predicated on the demise of the party.

When the PPP came back to power, it first swerved rightward in reaction to the earlier confiscatory governance, then turned jihadi as a part of the Pakistan army’s own evolution to a middle-class entity determined to oppose the “lack of principles” of politicians focused on survival. The unfettered pursuit of survival normally means freedom from principle, but it also leads to the collapse of ethics.

Bilawal says the party is not dead, but it may be dying as a dynastic party whose economic programme died long ago and whose political plank outside Sindh is wobbly. The Bhutto clan is divided and there is a Shaheed Bhutto PPP, run by the widow of the founder’s elder son, Murtaza.

Imitative of Nehruvian economics in the 1970s, the PPP revealed an intellectual blindness to state-sector socialism creating a global shipwreck. Even now, under the IMF regime, Pakistan is hard put to privatise loss-making enterprises like the Karachi steel mill (Pakistani Rs 1 billion a month), with over-employed armies of workers who don’t work. Corruption has proved corrosive. Intellect has been replaced with leftwing sloganeering.

The army doesn’t like the PPP — this is pivotal. And the Taliban somehow thinks its success is linked to the PPP’s annihilation. In Karachi, the majority muhajir (migrant from India) doesn’t elect the PPP. In interior Sindh, districts formerly devoted to the PPP are yielding to semi-terrorist seminaries of al-Qaeda-linked Sipah Sahaba, which has threatened its vote bank, while Sindhi “socialist” and nationalist parties wait for the Bhutto charisma to fade.

Source: