Attractions of the Islamic State – Ayaz Amir

Here is something for the Pakistani privilegentsia to consider. Something like the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham – Isis or Daish – would have catastrophic consequences for them, putting an end to their privileged lifestyles or forcing them to flee to the Gulf or western shores. But in the unlikely event of Daish becoming a force in Pakistan, how would this affect the poor and the down-and-out who have nothing to lose?

I lead a life of relative ease and comfort, earning some money from the little property I inherited but getting most of my money from my work in journalism. In the event of a Daish takeover in Chakwal – this being only a hypothesis – I would be a net loser.

But let’s calmly consider how I would be a loser. I would probably lose most of my property, the local Daish emirate in Chakwal telling me to keep my house plus one shop out of the property I own. Would this be such a bad thing? And suppose all the markets in Chakwal were similarly taken over, and former owners asked to keep only one shop for themselves, and double or treble ownership of houses done away with, the revenue of the Chakwal municipality, would jump 30-40-fold immediately. Is this a bad idea?

The local emirate would take over police functions. The DPO and SHOs would be Daish activists (and from the confiscated property they would get free housing). Every police constable would get some accommodation (again from the houses confiscated). The sessions’ judge and the other judges would have to flee for their lives, Daish activists taking over their functions. The backlog of cases would disappear and litigation would come down, to the great distress of lawyers. Punishments of course would be harsh, if not brutal, and would be meted out on the spot.

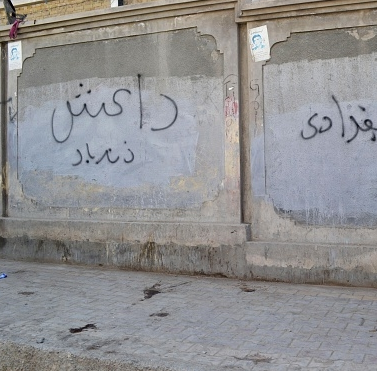

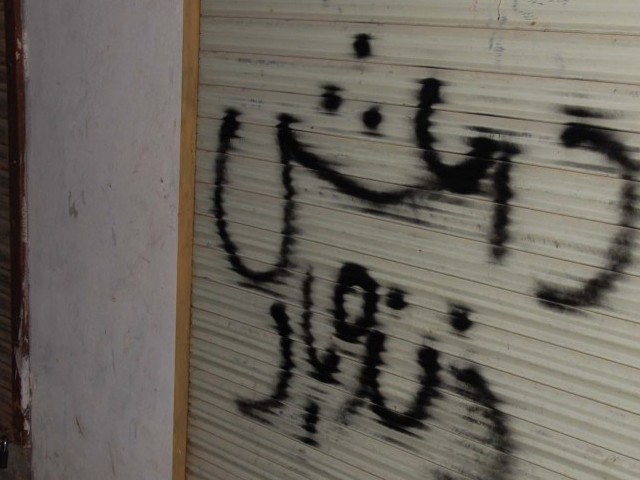

I am not saying this out of my head. This is what has happened in Daish-controlled territory in Syria and Iraq, especially the town of Raqqa in Syria which gives the feeling of being the capital of the Islamic State.

Writing in the New York Review of Books, Sarah Birke, a journalist with the Economist who has lived in Syria for three years, observes, “According to ISIS’s strict interpretation of sharia law, women must wear a niqab, men must not have pictures on their T-shirts, smoking is banned, shops must shut for the five prayer times…and only women can work in women’s shops.” Pakistan’s well-off classes, from where come the liberati, would consider these apocalyptic restrictions. But how do they affect the lower sections of Pakistani society for whom the niqab and pictures on T-shirts are scarcely earth-shaking problems?

She goes on to say, “Raqqa has also been a model for ISIS’s system of taxation: shopkeepers from Raqqa I talked to in southern Turkey told me the group takes 2.5 percent of their revenue, deemed zakat, the alms payment in Islam, and a monthly fee of 1,500 Syrian pounds, or roughly $8.30 (equivalent to about Rs800)…Locals also report that salaries are regularly paid to both civilian workers and fighters, who get $400 or more per month (that is, Rs40,000 or more).”

If zakat and a monthly fee were levied on every trader, shopkeeper and businessman in Pakistan I suspect – although I am open to correction – that our resource worries would lessen considerably. And at a monthly salary of Rs40,000 or more the emirate ensuring this would have an endless stream of fighters answering its call to arms.

The Afghan ‘jihad’ attracted fighters (so-called ‘mujahideen’) from across the Islamic world. But here’s the puzzle. “There is still a question”, says Birke, “which preoccupies American officials, of why ISIS has attracted so many fighters – the most rapid mobilization of foreign fighters so far, outstripping recruitment in the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan…according to jihadist experts.”

The answer, she says, may lie in ISIS’s extensive use of social media to attract recruits, the relative ease of moving across the Turkish border into Syria, and – most tellingly – “coming at a time at which governments in the region and in the West lack convincing ideologies and are seen as corrupt by their inhabitants, Muslim or otherwise.”

This is the nub of the problem. Corrupt oligarchies hold sway in most of the Muslim world. What attraction is there for their populations, who do not enjoy the comforts of the elites, to be loyal to these oligarchies?

The Saudis do not like the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. They do not like Shiite Iran. They do not like the Shiite Hezbollah, or the Shiite Houthis ascendant in South Yemen. The rise of Shiite power in Iraq is a cause of concern to them.

What is their answer to these prevailing currents? The thick-fisted exercise of chequebook diplomacy: handsome handouts to Field Marshal El-Sisi in Egypt, money to the Syrian opposition, and handouts even to Saudi Arabia’s own population. But a chequebook is just that…it is not an ideology. It has appeal for the oligarchies, such as El-Sisi’s oligarchy in Egypt, but what attraction does it have for the support base of the banned Muslim Brotherhood?

I couldn’t live for a day in a Daish dispensation. The loss of property I wouldn’t mind so much but imagine the cold comfort of evenings without my usual spiritual sustenance. Furthermore, forced prayers would go against my grain. About the usual run of maulvis the less said the better…so to be forced to stand behind any of them would hardly be a matter of enthusiasm for me. But, come to think of it, prayers on the pavement outside, as I have seen pictures of prayers being offered in Raqqa and elsewhere, would not be such an onerous obligation even for someone as lazy as me in the matter of his devotions.

But these are my scruples. My driver and cook and maidservant have none of them. Spiritual sustenance may be a problem for me, not for them. They get by perfectly well without Beethoven or Wagner. My driver doesn’t miss his Friday prayers. If he had to offer his five regular prayers I can’t imagine him thinking that the world was coming to an end. Rickshaw-travelling women prefer some form of hijab or purdah. How would a Daish emirate affect these different cases?

Pakistan may not be breaking down – and long may this never happen – but most of us are agreed that its structure is not functioning very well. What stake do the impoverished and the not-so-well-off have in this Pakistan? What is there in it for them? If you ask a madressah student to leave his seminary what answer will you give him if he asks, ‘what for’?

The ‘jihadi’ and the suicide bomber have at least the promise of paradise, the hope of everlasting bliss in celestial company (not to forget, the presence of houris). Call it a dream but there is this dream. Advertising and consumerism can manufacture dreams catering to the anxieties of the middle classes. But the down-at-heel Pakistani, what has he to look forward to? Leave reality alone. On the lines of the fantasy called the American dream, is there anything like the Pakistani dream for him? If the answer is no, then the state has a problem when it comes to fighting terrorism and combating the lure of radical Islam.

Let’s not forget that the radical Islamist has an ideology. Disagree with it as much as we may but it is there, a system of beliefs, a set of convictions. Apart from claptrap and outright nonsense what does the state of Pakistan stand for? Is our development model of shopping malls, housing for the rich and infrastructure development favouring the rich a sufficient formula for firing the imagination of the slum-dweller as much as it may touch the Gymkhana Club or Sindh Club member?

Break down the gates of privilege and try to create a more just society. But who’s interested in this? Politics in Pakistan has become a battle between competing oligarchies and there is not a single damned party speaking for the under-privileged or presenting an alternative to the shopping mall society. Keep on this path and Daish and the Taliban will not lack for recruits.

Source:

http://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-9-305325-Attractions-of-the-Islamic-State