Dangerous Divisions in the Arab World

Even in a region where violence has become all too commonplace, the killing of four Shiite men in Egypt last weekend seemed particularly vicious. According to news reports, a cheering Sunni Muslim mob armed with clubs, swords and machetes raided a house in a Cairo suburb where about 30 people were marking a religious festival and beat, stabbed and lynched the four men. Video footage showed the victims’ bodies, bloodied and motionless, being dragged through the streets. Among those killed was a prominent Shiite cleric, Hassan Shehata.

The incident illustrates a pernicious sectarianism that was largely repressed by pre-Arab Spring dictators but that now threatens Egypt and much of the Arab world. If left unchecked by newly elected leaders who either exploit simmering historical animosities or refuse to address them constructively, divisions will worsen between Sunnis and Shiites or between Muslims and other minorities, like Christians, ensuring prolonged regional turmoil.

In Egypt, President Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, the Sunni Islamist party from which he hails, have failed to unite the overwhelmingly Sunni country and its Christian and Shiite minorities around a centrist agenda in the post-Mubarak era. Instead, they have solidified ties with Salafist hard-liners in the Islamist camp; derided opponents, including many secularists, as “enemies of Egypt”; and demonized Shiite and Coptic Christian minorities.

The mob attack came after months of anti-Shiite hate speech; the week before the incident, Mr. Morsi appeared on stage at an event with hard-line Sunni clerics who denounced Shiites as “filthy.” Tensions over Mr. Morsi’s rule have been running strong for some time. On Friday, at least three people were killed and hundreds were injured in protests, and many fear violence during protest rallies set for June 30, the first anniversary of his inauguration. The army has warned it may intervene if things get out of control. Mr. Morsi’s speech to the nation on Wednesday offered little to appease critics demanding his resignation.

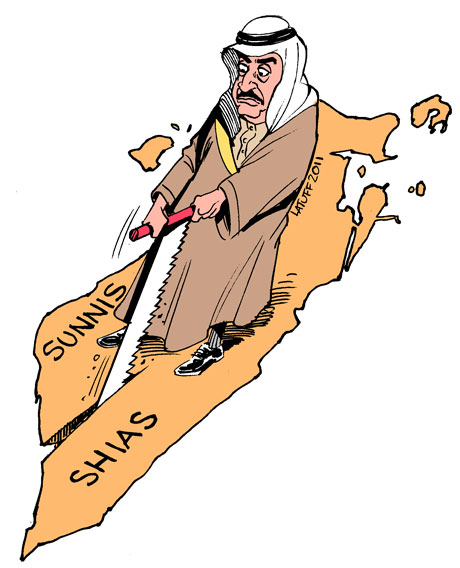

The sectarian problem, however, goes well beyond Egypt. In Iraq, renewed killing between Sunnis and Shiites has produced the highest death toll in five years. Part of the blame falls on Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki, who heads an elected Shiite majority-led government that has never made good on promises to re-integrate minority Sunnis, empowered under Saddam Hussein then banished after his ouster, into politics and the work force. In Bahrain, the royal family representing the Sunni minority has cracked down hard on protests by a Shiite majority population seeking a greater role in political life. Sectarian tensions are also roiling Lebanon and, less so, Turkey.

Every country’s situation is unique, but to a great extent the regional ferment has been stoked by Syria’s civil war as it spills across the border and ignites Sunnis and Shiites in neighboring states to also attack one another. The conflict began more than two years ago as peaceful protests against President Bashar al-Assad, a member of the minority Alawites, a Shiite sect. Now with 100,000 Syrians killed, Sunnis across the region have become incensed by Mr. Assad’s brutality against the mainly Sunni opposition, while Shiites from outside Syria have joined the fight to defend Mr. Assad. Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar — Sunni countries with broader strategic interests — are backing the Syrian opposition, while Iran and the Lebanon-based Hezbollah, both Shiite entities, are backing Mr. Assad.

Regardless of what happens in Syria, leaders in neighboring countries need to move quickly to reverse the sectarian slide. That means stating unequivocally that they are committed to the equal rights of all citizens and to ensuring that Shiites and other minorities can practice their religions without fear. Such principles are embedded in the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. More broadly, it will require an acknowledgment that elections do not alone produce democracies; that governments need to be inclusive; and that nurturing hatreds, for whatever reason, inevitably backfires and makes stable societies impossible.

Source :

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/29/opinion/dangerous-divisions-in-the-arab-world.html?_r=1&