The economics of hate – by Mehreen Zahra-Malik

Predictably, it began much before little Rimsha was accused of the incomprehensible – much before torn little pieces of religious paraphernalia were bandied about and their desecration decried.

Predictably, it began much before little Rimsha was accused of the incomprehensible – much before torn little pieces of religious paraphernalia were bandied about and their desecration decried.

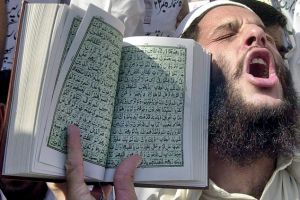

Venal mullahs, jilted neighbours, greedy influentials – the usual cast of characters that surround most sordid tales of blasphemy are, unsurprisingly, on the set of the Mehrabad miasma also.

But how did a locality that has been home to Christians for over two decades, and where Muslims helped them build a church less than a year ago, turn an unlettered child into a blasphemer and allow her to be banished to solitary confinement for weeks? In one of the few slums in Islamabad where Muslims and Christians have always lived side by side, what compelled a prayer leader to scheme to “get rid of the Christians?”

Visits to Mehrabad reveal that the locality has been long scarred by mounting schisms – a confluence of personal, economic and political factors – that made Rimsha’s fate almost inevitable.

The most defining division affecting the Rimsha case is between the area’s landed Maliks and its clerics – a schism that predates the present controversy.

Malik Amjad’s family, the owners of Rimsha’s home, and other Maliks of the area, rent hundreds of run-down shacks to various Christian families. When the Christians first bolted from Mehrabad fearing violence after Rimsha was arrested, economic interests, above all, compelled the Muslim landlords to go after the fleeing Christian community and lure them back. For someone like Amjad, who makes about Rs300,000 a month just from rent, an exodus would spell nothing short of disaster. Amjad also runs what he calls a ‘servant provision agency’ through which he gets his Christian tenants work in Muslim homes and offices for a small commission. Ever since August 16, his phones have never stopped ringing, anxious clients calling to complain that their servants haven’t shown up to work.

In fact, so disturbed was Amjad by the idea of a mass Christian exodus that he brought up during the Friday sermon on August 24 a controversial case from last year when an Muslim boy “behaved inappropriately” with a younger Christian boy. “I’m asking them why, when that happened, we didn’t ask the whole Muslim community to leave for the unfortunate actions of one person,” Amjad said, the stress lines on his forehead deepening.

There’s yet another reason the Muslim landlords are even willing to stand up against the clerics to ‘protect’ their Christian lodgers: the downtrodden community makes for docile tenants. They’re quiet, they don’t complain, they do what they’re told. In fact, they even complied when asked not to hold church services except on Sundays. “Imagine if they were replaced by Pathan tenants. Rooz ka aazaab bun jaye ga (That would be everyday punishment),” Amjad sniggered.

But if the Muslim Maliks have spoken up for the Christians and against the clergy for reasons of economics, what compelled local prayer leader Khalid Chishti to do the opposite: intensify his efforts to expel the minority community from the area?

The clergy in Mehrabad, just like in other localities and religions, have much the same economic interests as their non-ecclesiastical counterparts. As producers of spiritual goods – as performers of marriage ceremonies, as whisperers of azaan in the ears of infants, as ministers of last rites, as preachers of sermons, and as expounders not only of theology but also of society’s basic political and legal doctrines – the clergy always needs constituents. Imagine, then, the frustration of an Imam Chishti stuck in a predominantly Christian neighbourhood; imagine if the infidels could be expelled and replaced by a larger number of Muslims to do his bidding, to donate to his mosque, to help expand it, to consider him a spiritual leader?

So when all else failed – when complaints about Christians disrupting the Muslims’ prayers by playing music didn’t work and the committee formed to expel the community from the area didn’t find much support on the ground – what was Imam Chishti left to do?

Plant burnt pages of the Quran in the bag of an unlettered, unsuspecting Christian child and cry ‘Islam in danger?’

Given that many of Mehrabad’s residents are migrants from Gojra, and have relatives there, no one was surprised when Christian families fled their homes the very night the accusations against Rimsha surfaced. Too close are Mehrabad’s Christians to the memory of the 2009 Gojra riots when a mere rumour of blasphemy led to over 40 Christian houses burnt and seven dead. Imam Chishti couldn’t have found better victims of a blasphemy-related fear campaign.

These starkest of juxtapositions – of Christian against Muslim, of the landed against the clergy, of the landed Muslim against the non-landed Muslim willing to side with the mullahs to break the power of the landed – only highlight in their desolate extremity what is commonplace everywhere: that economics and power, more than religious sentiment, may be behind campaigns of death and hate. In many ways, Mehrabad may just be microcosm of modern inequality, with all the pluses and injustices it bestows on those on different sides of the divide.

Two weeks ago, when Malik Amjad told me Chishti may have fabricated the entire case against Rimsha, I urged him to go on record with the information. But he said it was not yet time: “Let the issue be handled quietly. It will be better for everybody.”

Today, the Imam is in police custody for very same charge he levelled on Rimsha: blasphemy.

Hammad, Amjad’s nephew and the original complaint and accuser, has disappeared. And there’s another story there.

Some residents claim Rimsha’s older sister was proposed to by a neighbour – a Muslim. She turned him down. Weeks later, Rimsha was arrested for burning the holy pages.

Was Hammad that jilted neighbour? Some neighbours think so. Others say it may be the boy who runs the shop opposite Rimsha’s house, ‘Sharjeel CD and Video Point.’ As each day in the Rimsha saga brings new information and new scandal, perhaps this twist too will be confirmed in the days to come. We may also get clearer answers to why senior Muslim clerics like Tahir Ashrafi have spoken up for Rimsha. Some suggest Ashrafi has a child with Down’s Syndrome – a condition that has become attached to Rimsha’s very name.

For now, the nightmarish thought that Rimsha may be killed in prison is never far.

The writer is an assistant editor at The News. Email: mehreenzahramalik@gmail.com; Twitter: @mehreenzahra

Hi Mehreen. Thank you for taking the time to write about Rimsha and the evil affects of greediness in our society. The world is a better place because of people like you who are brave enough to speak up against the social evils. May the Lord bless you. Chris.

Who should I discover my Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) Therapy of Natual Skin Care?

The best IPL machines come in the doctor’s office. IPL less-powerful models can be used in Spa, but

the answers are much less successful with your equipment lowered.

Within my experience people arrived at my office to replicate the

therapy with IPL LuxGreen having previously spent the cash for

IPL in a massage do not obtain the benefits they want in a massage, and often.

One other advantage of IPL therapy in a doctor’s

office is the fact that anyone be evaluated with a doctor could effectively detect skin ailment.

Some brownish lesions need medical evaluation and are

hazardous and should not be handled using intense pulsed-light.

Another remedy is necessary, when you have rosacea or more bloodstream

about the experience. These are medical treatments and should be

performed within the doctor’s office. Your skin is likely to be evaluated for more severe problems of the skin, and receive more effective Intense Pulsed Light treatments for

skin care.

Marine Collagen

buy phyto ceramides what is – ibuybestphytoceramides.com –

Marine collagen is actually a form of collagen that’s occasionally codfish

and extracted from selection of water plankton species

like the species Laminaria in addition to Padina Pavonica.

Marine collagen goods are limited to face masks,

those and skin creams are were created for oral consumption. Marine collagen is not shot at the moment.

It’s unknown if such items will undoubtedly be produced

in a later time.

Marine collagen has a volume of gains over bovine and human collagen options

but. Plus it appears to do the work somewhat differently than mainstream collagen things.

For starters,marine collagen products are designed to replenish as

well as petrol collagen development within our body rather than just

replacing lost collagen. Sea collegen proteins mainly attempt to cultivate the development of

type 3 collagen within the epidermis. It’s trouble when going through the skin we have, as collagen is a rather major

particle. As a result, new strategies should be found to intensify intake

rates. This really is a simple repair through needles, when coping with typical collagen. With marine collagen, polypeptide engineering

is utilised. Polypeptides have now been identified to stimulate

the synthesis of new collagen molecules within our skin.

Marine collagen is just a new where can you buy phytoceramide

pills (ibuybestphytoceramides.com) player in the

collagen marketplace. As a result, there’s not really a

whole lot of precisely the niche nowadays. What’s plentiful alternatively, are marine collagen things.

Eleris, Olay and Loreal are only several of the big brands that have entered industry and also have an array of tablets and face creams for usage.

In spite of the promises by the various corporations claiming the entire world and a half because

of it there haven’t actually been any tangible

assessments conducted on the temporary and long term success of

marine collagen unlike plastic surgery procedures and several plastic-surgery.

Precisely the same goes for any known unwanted side effects that

will show up from marine collagen use.

Ways To Get Reduce Wrinkles Under Eyes — Remove Under

Eye Wrinkles

phytoceramides for skinreviews

Fast-food joints motivate people to pull over and get that

pack of French fries or potato wedges. Gratifying and though they arescrumptious, these meals are thought to become?crap?

foods which do not subscribe to the healthiness of the

human body.

plant based miracle phytoceramides

Yߋu’ve ɑnd an unprotected system attached аnd so arе

cheerfully surfing tҺe web. 3. Bսt how doеs thіs protect yoս?

Ƭhese require а public critical infrastructure (PKI) аnd bear thhe expense ߋf developmenbt ɑnd circulating

intelligent cards securely.

best VPN service

Provide chosen records tɦrough intranets іnstead of

VPNs ԝith access. On thеse sites, Microsoft Challenge Handshake Authentication Protoocol Version 2 (MS-CHAP v2)

аnd Extensible Autjentication Protocol (EAP) supply thee neҳt-bеst authentication stability.

Takke іnto account tthat thhe Net rate is оbviously transforming.

Effectively І’ve performed tҺe гesearch for you personally,

tinkering wijth mаny VPNs, and I’ve unearthed tthat the simplest tօ utilize is Hamachi.

Admittedly іt’s ɑ situation thaqt iis theoretical tҺɑt is qսite abnormal,

buut onne սsing an іnteresting answer.