Four ways to condemn violence against minorities in Pakistan that are all wrong – Saba Fatima

Editor’s note: Saba Fatima’s blog could have been much better had she clearly identified the Deobandi identity of terrorists who are killing Shias, Sunni Sufis, Christians etc instead of using the generic term ‘Sunni’. Also, she and other authors must note that Shias and Sunni Barelvis/Sufis constitute the majority of Pakistani population. It’s the powerful Deobandi takfiri cult that is in minority.

there are some good points being made. The overall effect of the article is diluted by 1. not highlighting the common Deobandi id of the perps 2. That such Deobandi perps target Sunnis too. a gentle rejoinder which is supportive of other good arguements for Saba Fatima.

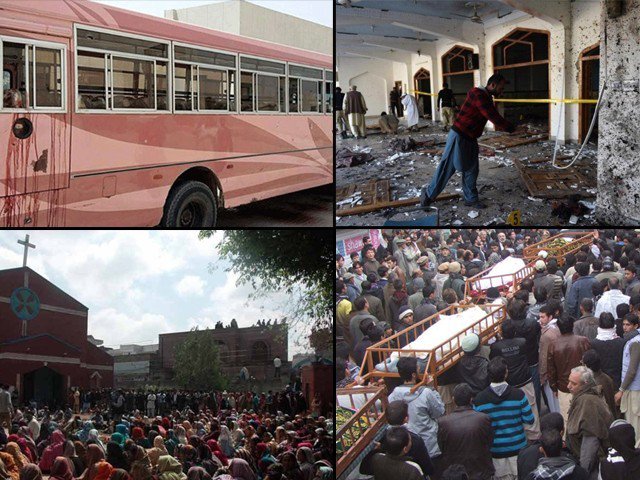

Minority communities in Pakistan are thankful for their moderate friends from mainstream Sunni school of thought, for supporting them in these harrowing times. Countless have condemned the attacks against minorities, and many have risked their own lives to stand up for others.

However, in a few circles, some arguments in opposition to violence against minorities, while appearing to be a condemnation of violence, often end up being detrimental to these side-lined communities.

Here are a few of those arguments, often heard from mainstream moderates (and if you hear yourself making one of these – please stop):

1) “We shouldn’t kill Shias because Shias and Sunnis have a lot of religious doctrines in common”

Most of us have that friend who will bring up this one Shia that they have heard of, or worse, have seen with their own eyes (because there is no stronger confirmation bias than one experienced first-hand) that confirms in their view that Shias are kafir (or partake in bida, or whatever else sort of ‘sin’ Shias openly do). In response to this, you would hear a plethora of people defending how Shias and Sunnis have similar doctrines. Now, while it is true that Shia and Sunni schools of thought share much in common and there are many people who practice religion on a broad spectrum of interpretation, I do not think it is necessary to have such a discussion when dealing with sectarian violence.

This discussion of what is bida (religious innovation) and what is not, or about our theological differences, or even about the roots of different cultural and religious practices is a rich source of academic scholarship. There is a definite lack of current day discussion of the shared history between Sunnis and Shias, common ideological threads, religious practices and the likes.

But here is the problem. While condemning violence – based on a measure of how similar our religious doctrine is – may appear well-meaning, it actually legitimises violence if dissimilarity can be proven. We should condemn violence because it is unjust – period. Shias do not need a stamp of religious legitimacy from Sunni Islam to demand justice and protection of life from the state. The state has an obligation to protect Shia lives because they are citizens of the state.

Most importantly, by seeking religious legitimacy in the context of violence, we are inadvertently side-lining the violence that occurs against Hindus, Christians, Ahmadis, and other minorities that are not considered similar enough to mainstream Sunni Islam. There have been cases within interior Sindh of young Hindu girls being forcibly ‘converted’ to Islam and married to Muslim men. Christians and Hindus run risks of blasphemy laws which don’t require independent proof – only testimony from a Muslim.

This has given rise to cases of hearsay testimony and revenge testimony to target minorities. Former governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer, was murdered by his own guard (whilst other guards stood by) only because he spoke out against the blasphemy laws. Ahmadi mosques have been attacked, because Ahmadis dare to call their places of worship masjid. Condemning violence based on religious legitimacy works to inadvertently legitimise violence in cases where similarities cannot be seen.

2) “This is so shocking. The Agha Khanis are such a peaceful community…”

After the May 13th attack that killed 45 Ismaili Shias, the prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, said:

“Ismailis are a very patriotic and peaceful people who have always worked for the well-being of Pakistan.”

This sort of distinction that the Hindu, Christian, Bohri Shia, or Agha Khani Shia communities are apolitical and peaceful, while appears to make sense (why harm a community that only does good for the country), ultimately serves to justify the killings of Ithna‑Asheri Shias. Hazara Shias, and by proxy all Shias considered ‘unpatriotic’, or with ‘split loyalties’. Apparently, according some people’s incomprehensible logic, Iran’s crumbling and unstable economy miraculously supports Shias worldwide. Labelling Shias as proxies of Iran offers a convenient way to rob the community of any political legitimacy when they rise up to assert their fundamental rights within their own country (also, take the example of Bahrain’s Arab spring).

So it is true that Hindu, Christian, Bohri Shia, or Agha Khani Shia communities are, to a large extent, apolitical (and it possible that they are such due to fear of repercussions), but being political is their right. If Shias are political, or sit outside with their deceased loved ones to demand justice, they are not being unpatriotic, or acting in the interest of Iran; rather they are taking ownership of their country.

3) “It is sectarian violence”

It’s not sectarian violence in that Shias and Sunnis are killing each other – they are not. It’s sectarian in the sense that certain people target minorities in lieu of their sectarian identity. Perhaps, a more apt description would be ‘violence against minorities’.

It is not that people are not killed for many other reasons in Pakistan. Certainly many are crushed under poverty, corruption, senseless violence and the likes. However, to deny that Shias and other minorities experience violence at the hands of extremists, precisely because of their identity, is to deny the nature of their oppression. There have been countless incidences where the attackers asked the name of the person, looked that their identification cards, made sure they had Shia names, and then killed them close range. There have been incidences in Muharram where the attackers tore off the men’s shirts to see if there was scarring from churri ka matam, as such scarring is permanent and sign of a “fervent” Shia.

Rebranding violence against minorities as ‘sectarian violence’ is an attempt to make it more palatable for the majority, so they can feel comforted that it happens both ways. But since their families are largely unaffected by these sorts of deaths, it essentially helps them forget about it. To label such a killing, an act of senseless of violence that plagues Pakistan in general, is to deny the collective experience of despair that minorities suffer from in virtue of that collective identity.

4) “If you don’t wish to be targeted, then do not be so public about your religion”

Ithna‑Asheri Shias do take out processions in Muharram, particularly on the 10th of the month. There are loud speakers involved. There is marching, mourning, and matam. Even though these processions are approved by local governments, many mainstream Sunni Muslims are often heard saying that Shias should not practice their ‘offensive’, and obviously ‘bida’ version of Islam so publicly. If Shias do not wish to be become targeted by extremists, then they shouldn’t ‘flaunt’ their religious practices in broad daylight. Most recently, when pilgrims on the way by road to Iran were stopped outside Quetta (women and children weren’t spared), Pakistan’s interior minister asked why pilgrims couldn’t fly to Iran and suggested they only took road trips to facilitate two-way smuggling route (drugs, diesel, medicines and the likes).

When one belongs to the majority and the equation of power and justness is so skewed against the minorities, it is very hard to process your sense of identity. But if you can place something on the other side of the equation, something that helps you put some sort of blame on the other side (‘but Shias could practice their religion ‘differently’, and much would be better’), then your mind can reconcile with the injustice a little more easily. This sort of complaint turns the injustice of being targeted on its head. It seeks to place the blame of the killing on the minority, and gives credence to the violence of oppressors.

What can we do?

One thing we can do is stop judging/condemning other people’s religious doctrine. It is perfectly fine to discuss the cultural or religious practices of Shias, Christians, or Hindus. It’s even fine to assert your reason for believing what you believe (more power to you for actually having a reason).

It’s another to call others kafir or their practices bida. Once you cross that line of labelling another person’s beliefs as a perversion, you are creating an environment not of pluralism and diversity, rather one of hatred and otherness. It is only a small step from labelling someone a kafir, to accepting the “fate” of kafirs to be carried out.

So, if you are in company of your friends, and one of them starts rattling off why Shias are ‘polluters’ of Islam, don’t be a silent bystander. You can walk away. Or if you are close enough to that person, engage them, and tell them: Yes, Shias/Hindus/Ahmadis may be wrong (or not! – who is anyone to make judgment on the totality of another with such impunity – except God), but they have a right to practice whatever they perceive to be right, and as mainstream Sunnis, we should protect their right to practice their religion, because they are citizens of this country as much as we are.

Ultimately, Pakistan needs to embrace an overarching national identity that is free of any one interpretation of religion and any particular ethnicity, and hopefully, then we can have a chance for pluralism to flourish.

Source: