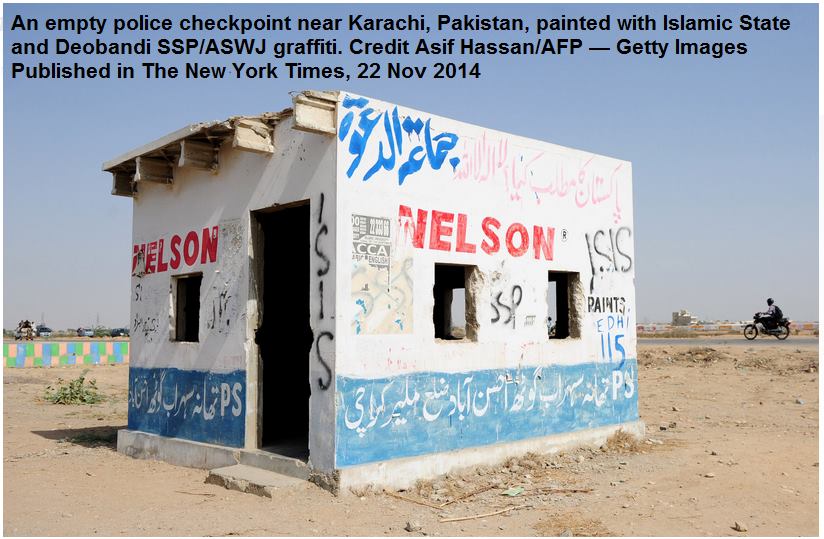

Graffiti in support of the Islamic State in Karachi, Pakistan. Even a symbolic presence of the group has raised concern. Credit Shakil Adil/Associated Press

“It doesn’t matter that Daish has not yet established its presence in Pakistan — it has already changed the dynamics of militancy here,” said Muhammad Amir Rana, director of the Pak Institute for Peace Studies , using the group’s Arabic acronym. “Our groups were in crisis; now Daish has provided them with a powerful framework that is transforming their narrative.”

During his visit to Washington this week, the new Pakistani Army chief, Gen. Raheel Sharif, assured his American hosts that the Islamic State would not be allowed to take root in Pakistan. Instead, officials say, local groups are manipulating its name to their own ends.

When Islamic State posters appeared on electricity poles in Lahore, the hometown of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, this month, the police blamed it on Deobandi militant groups like Lashkar-e-Jhangvi . “They are just using the Daish name to intimidate Shiites,” said Ijaz Shafi Dogar, a police commander.

Even nonjihadist groups have seized upon the potency of the Islamic State brand. In Karachi, secular politicians have claimed that Islamic State graffiti shows how militants are slipping into the city amid an influx of Pashtun migrants — a contention angrily rebutted by Pashtun leaders.

“It is totally exaggerated, and an attempt to slur our community,” said Abdul Razzaq, a community leader.

But inside the splintering network of the Pakistani Taliban, the Islamic State phenomenon has had a very real effect as a powerful catalyst for tensions.

As a punishing military offensive against militant cells in the North Waziristan enters its sixth month, the Islamic State has highlighted to militant leaders the shortcomings of their own insurgency and provided an outlet for dissent.

The ISIS cause became openly divisive in October when a group of six commanders led by Sheikh Maqbool, a former Taliban spokesman, openly pledged loyalty to the Islamic State. “A large number of mujahedeen are with us,” said Abu Zar Khurassani, a senior figure in the breakaway faction. “Soon we will decide on how to help the Islamic State.”

The split was partly a product of simmering disputes inside the Taliban leadership, said a Taliban commander in Peshawar, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. But, he added, many fighters were inspired by the dramatic video images of Mr. Baghdadi, draped in a black cloak, declaring a new caliphate.

He presents a stark contrast with the Afghan Taliban leader, Mullah Muhammad Omar , who has been nearly invisible since American airstrikes drove him from Afghanistan 13 years ago.

“The mujahedeen are raising questions about how we can follow someone whose presence has not been confirmed for the past decade, except for greetings at Eid,” said the commander, referring to an annual Islamic holiday. “We don’t even know if he’s dead or alive.”

Although the Islamic State has extended its franchise and resources to at least one other foreign militant movement, Ansar Beit al-Maqdis , which is battling Egypt in Sinai, such recognition has not been publicly granted to any Pakistan-based groups. In a video message, Mr. Maqbool, the breakaway Taliban commander, said he had tried to reach the Islamic State over the summer, using Arab intermediaries, but had yet to receive a reply.

Continue reading the main story

GRAPHIC

Areas Under ISIS Control

A visual guide to the crisis in Iraq and Syria.

Yet there are also signs that the Islamic State’s leadership is aware of its Pakistani constituency and wishes to pander to it.

In the summer, the Islamic State publicly demanded the release of Aafia Siddiqui, a Pakistani scientist serving an 86-year prison term in the United States for her part in an attack on Americans in Afghanistan, in exchange for the American journalists James Foley and Steven J. Sotloff, who were later beheaded.

“That’s quite important,” said Zahid Hussain, author of “The Scorpion’s Tail,” a book about the rise of Islamist militancy in Pakistan. “It shows they knew who Aafia Siddiqui was, and that they wanted to have some kind of influence on the Pakistan groups.”

In fact, there are important connections, historic and current, between the jihadist fronts in Pakistan and the Middle East.

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian militant commander killed by American forces in Iraq in 2006 , lived in Pakistan and Afghanistan for long spells during the 1990s and early 2000s. The eruption of civil war in Syria in 2011 drew a steady traffic of fighters from militant groups, both foreign and local, based in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border area.

“The linkages are old,” said one senior Pakistani security official in Peshawar, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “They went quietly — not in droves but in ones and twos.”

Recruiters draw on Pakistan’s broad pool of extremist and sectarian militant groups; most recently Saudi-funded groups have recruited fighters from Baluchistan Province, where violence against Shiites is high, said Mr. Hussain, the analyst.

Some fear those fighters could return from the Middle East imbued with an invigorated sense of purpose — and money from Iraqi oil fields — to further stoke Pakistan’s own wars.

“We don’t discount the emergence of a new militant front in the region that has a direct nexus with Islamic State,” the security official in Peshawar said.

Tentative contacts have begun, according to some intelligence reports. In an internal letter last month, officials with the Home Department of Sindh Province warned that an Islamic State representative from Uzbekistan had appointed Abid Kahot, a militant commander based in Rawalpindi, to draw Pakistani groups into the Islamic State’s orbit. The letter was seen by The New York Times, but its authenticity could not be confirmed.

Still, other Pakistani officials are skeptical that the Islamic State could change much in a country that has already suffered years of suicide bombings, beheadings, drone strikes and several tens of thousands of deaths. “In tactical terms, it would change nothing,” said one government official in northwestern Pakistan.

The last jihadist conglomerate group to create such a frisson among Pakistani militants was Al Qaeda , which remains the predominant foreign group in the country. But its ranks in the tribal areas have been hit by more than 400 American drone strikes in the past decade. And the messages from its leader, Ayman al-Zawahri, mostly in lengthy and static video and audio recordings, look dated alongside the nimble social media of the Islamic State.

Apparently seeking to bolster his support in the region, Mr. Zawahri announced a new franchise, named Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent, in September. This month, the group’s spokesman, Usama Mahmood, called on rival jihadist groups in Syria to unite against the United States. And on Friday, the Qaeda branch in Yemen condemned the Islamic State’s declaration of a caliphate as a divisive power grab.

Failure to face up to the threat of the Islamic State could pose a greater danger to Pakistan than Al Qaeda did, the English-language newspaperDawn warned in a recent editorial . “Miss the warning signs now, or fail to deny it space within Pakistan,” it said, “and it may not be long before I.S. becomes the mother of all militant problems.”

LONDON — Across Pakistan, the black standard of the Islamic State has been popping up all over.

LONDON — Across Pakistan, the black standard of the Islamic State has been popping up all over.