Saudi Wahhabis turn the house of Prophet & Khadija into public lavatories

Millions of hajj pilgrims are preparing to head home, after five days performing ancient rites, revering a God omnipresent in the city of Mecca.

They have stoned figurative devils, they have slept in the world’s largest tent city, they have drunk water from the Zamzam well together: a heaving throng of nearly two million people from all over the world.

Circling the Kaaba, the black cubic epicentre of this sanctuary city, pilgrims would have looked up to see one of the minarets of the Grand Mosque, dwarfed by Abraj al-Bait clocktower, a much-maligned luxury hotel and commercial complex and the second-tallest building in the world.

Next year, they will see the Abraj Kudai, the largest hotel on Earth.

Indeed, though rebuilt throughout the centuries, the minarets – like much of the city – are now relics of a pre-modern Mecca. Cranes and scaffolding now dominate the central skyline, reminders that the city is undergoing a massive state-run expansion to be able to handle ever-increasing numbers of annual pilgrims in the future.

But as much as these pilgrims – as much as any Muslim – belong to Mecca for those five days, they are but spiritually home. When it comes to the city they visit out of religious obligation and devotion to God, most are transient figures, who will leave no indelible mark on the city. They leave behind two million locals, who are struggling with the impacts of the changing nature of their city.

In the 1960s, before travel became more affordable, hajj pilgrims numbered roughly 200,000. According to Mecca’s mayor, today there are two to three million of them, with an additional 12 million performing the lesser pilgrimage of umrah, which can be done at any point throughout the year. Faced with a dip in oil prices, revenue from Meccan tourism is expected to become a greater source of revenue for the Saudi Kingdom’s economy. Under its current plans, the city expects to add several million more pilgrims a year by 2020.

Estimates vary, but only a handful of Mecca’s millennium-old buildings remain. Ottoman fortresses and hills have made room for the royal clocktower. The prophet’s first wife Khadijah’s home is now the site of public lavatories. But very little is said about the thousands of homes and neighbourhoods destroyed to make way for the city’s expansion. Thirteen of Mecca’s 15 old neighbourhoods have been razed and rebuilt to make room for hotels and commercial spaces.

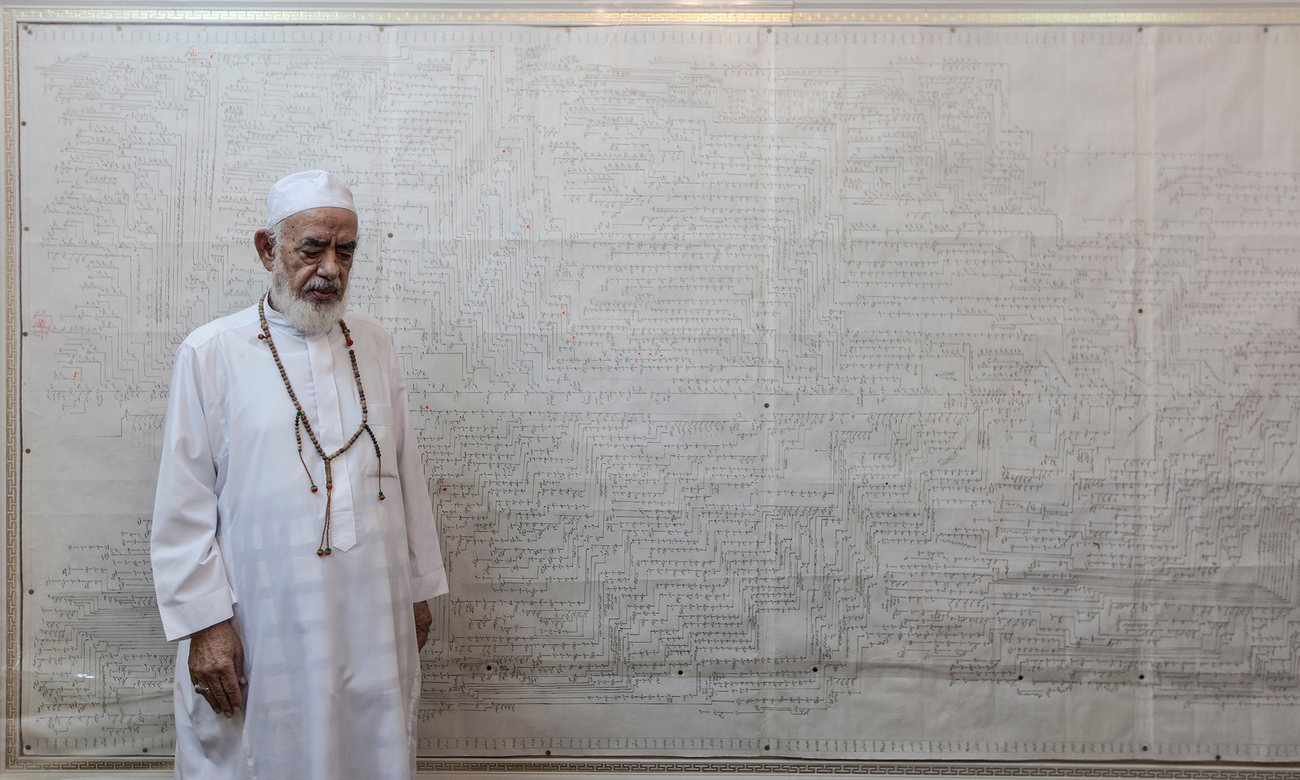

No one knows this better than Sami Angawi.

An architect who now lives in Jeddah, Angawi spent his childhood in his family’s ancestral home of Mecca. Like many Meccans, then as now, his father was a local guide to pilgrims there for umrah or hajj. As a boy, Angawi has said he would help his father carry around pilgrims’ shoes while they prayed.

The Angawis lived in Shab Ali, the neighbourhood said to have been the place of the prophet Muhammad’s birth. But their home was demolished as part of the first organised expansion of the Grand Mosque in the 1950s. Angawi told Al Jazeera last year that his family was forced to move two more times as the city continued its forced expansion.

The 65-year-old architect is also the founder of the Hajj Research Centre, who has spent the last three decades researching and documenting Mecca and Medina’s historic sites. “They are turning the holy sanctuary into a machine, a city which has no identity, no heritage, no culture and no natural environment,” Angawi told the Guardian in 2012.

His story is typical of many Meccan families: people whose livelihoods have long depended on the hajj economy but who, subjected to the new era of Mecca’s expansion, are growing increasingly resentful.

According to Jawaher al-Sudairy, a Saudi academic at Harvard’s Kennedy School, Mecca’s residents have had to continually “adjust their income, employment and way of life” to adapt to a city that is increasingly trying to erase them.

“And this attempt to [change] the city … is creating hostility,” Jawaher says. As neighbourhoods are razed, informal economies that kept entire communities alive – be they vegetable sellers, cobblers or informal tour guides – are being jeopardised.

More and more residents are facing challenges to participate in the hajj economy, and having to compete with corporations: hotels replacing private homes, fast-food chains replacing food stalls in once-bustling street markets.

“Some [Meccans] are upset that they’ve lost what some would call their ‘monopoly’ to another” corporate monopoly, says al-Sudairy, who has interviewed dozens of residents in recent years and researches the socioeconomic impacts of development on Mecca’s communities.

The only guaranteed high-income source is for those families who own property. Meccan families who now live outside the city have long rented out their homes to migrant pilgrims.

“When they rent during hajj season, the income they get can then sustain them for the rest of the year,” says al-Sudairy. “This is not an exaggeration.”

But with one square metre of land in the area surrounding the Grand Mosque now valued at £100,000, many have sold property either to the government, or to real estate developers – thus severing their historic ties with the city.

This has meant the greater proportion of the city is now owned by commercial real estate developers, and driven by private-sector interests.

It is an inherent tension, accentuated by the country’s increased financial woes, that Mecca must prioritise its migrant pilgrims over its residents, even though both populations are inextricably intertwined.

Perhaps most vulnerable of all are the city’s immigrant communities.

Mecca has historically been a beacon for Muslim immigrants. According to al-Sudairy, 45% of Mecca’s current population are non-Saudi immigrants. This includes second- and third-generation immigrants who are not entitled to Saudi citizenship.

Some are older and more established communities, like the Burmese who number roughly 250,000. Others, like the Nigerian and south Asian communities, are newer and comprise of seasonal workers employed in the construction and service sectors.

“In many ways the Burmese are the success story in Mecca,” al-Sudairy says. Though insular, Mecca’s Burmese are also highly organised. Unlike other immigrant groups, the Burmese have come to Saudi Arabia in waves since 1948 to claim political asylum. As such, many were granted the right to permanent residency in 2015 a first for the Saudi Kingdom.

But other migrant groups aren’t usually as lucky.

Many undocumented migrants live in Mecca, many of whom have overstayed their hajj visas. Some are inspired by the sanctity of the city, others come to earn a living and yet others, elderly Muslims, go there to die.

There is no official data, but by and large, “the government allows them to persist” and turns a blind eye, according to al-Sudairy.

“Politically, to force Muslims to leave Mecca just doesn’t look right,” she says. “Every Muslim feels Mecca is a second home.”

But they are still left vulnerable.

With the city deliberately turning the city centre over to commercial enterprise, residents are being pushed to the physical margins. According to the 2011 city master plan, residents were all to be relegated to an area called “Mecca gate”, a 16 sq km neighbourhood, with plans for affordable housing.

But in practice, once their homes are torn down and they receive meagre compensation if any at all, Meccans have been moving to neighbouring villages an hour away from their city, where they have gone on to build new slums.

Source:

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/sep/14/mecca-hajj-pilgrims-tourism?CMP=share_btn_wa