Josh Malihabadi – South Asia’s apostle of secular humanism – by Pervez Hoodbhoy

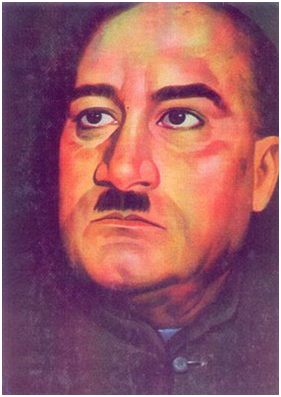

Shabbir Hasan Khan (December 5, 1898 – February 22, 1982) of Malihabad, known by his nom de plume as Josh Malihabadi, was not a particularly popular poet in his native land, India. For reasons that are not entirely clear, a decade after Partition – against the advice of his friend Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru – he chose to migrate to Pakistan. But Pakistan, where he lived his final years, turned out to be even less enamored with him than India. The man on the street today, assuming he has heard of Josh, would probably associate the name with the lyrics of certain popular film songs, or perhaps with his somewhat raunchy autobiography yaadon ki baraat. Apart from this, looking around in bookstores in Islamabad, one finds that his other works are unavailable.

Those steeped in the high culture of Urdu poetry do not really care. They know well the power and exhilarating beauty of Josh’s literary creations. His dexterity and genius in transposing thoughts into words created new thoughts and expressions. Poetry flowed from his pen like water from a bubbling spring – he is said to have authored well over 100,000 shairs (couplets) and more than one thousand rubayaats. Some among them represent the finest that Urdu poetry has to offer. This puts him into the pantheon of Urdu poets alongside giants like Ghalib and Iqbal.

But it still bothers one as to why this prodigiously prolific poet has not received, to date, recognition commensurate with his literary achievements. Perhaps one should not be surprised. Almost by definition, an iconoclast is not supposed to be popular in his own culture or country. Indeed, those who dare expose deep dark truths are likely to be reviled rather than praised. Josh the secularist, deeply unhappy about the partitioning of his country on the basis of religion, should not have expected to find recognition in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. And he did not! It is said that at his funeral there were only seventeen persons present – this in a country where oftentimes many hundreds, or even many thousands, turn out to mourn the departed.

Does iconoclasm explain away Josh’s lack of popularity? Perhaps this is being a bit too glib. After all there are Urdu poets who also belonged to the genre of ideological and political dissidents. Some eventually did attain fame and acclaim during their lifetimes. Among Josh’s most celebrated dissident contemporaries were Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Habib Jalib, and Ahmad Faraz. Now that there is no squint-eyed General Zia-ul-Haq and his goons to muzzle them, their verses have found their way into rather staid drawing rooms, and are even sung and recited on television. So why is Josh, who passed away even earlier, mysteriously absent?

Perhaps there are other answers as well. Josh’s poetry is complex in thought, rich in structure, and uses alliterations and allusions that are subtle. The language is oftentimes difficult: its comprehension requires a vocabulary wider than that of the average Urdu reader. Although a century ago they would have been easily understood, many of the words he casually uses have become arcane and unfamiliar. This is still truer in the birthplace of Urdu – India – where the language is increasingly marginalized, vulgarized, and stripped of its grace and finery. Moreover, contrary to later trends of Urdu poetry, azad sha’aree or free verse was always anathema for Josh. As a stickler for rules, he insisted upon purity of form and adhered to its rules as though he was composing some deeply classical musical raga. So, another possible answer could be: Josh is for the connoisseur, not the masses.

In this short essay I shall draw from Josh’s poetry examples that reflect his weltanschauung. His rebellious pen directs withering criticism upon the existing order, challenges those who draw boundaries between peoples, and advocates rational thought over dogmas of the Marxist left or the religious right. His libertarian views and contrarian lifestyle set him apart from the crowd. The conclusion is that this remarkable poet was shunned because his message was too radical for those times, and is even more so today.

A Quintessential Libertarian

Three hundred years ago, philosophers of the European Enlightenment period struggled to define the limits and meaning of individual freedom and liberty. Are these always good things, or only in particular situations and circumstances? When should liberties be curtailed, if they must? The classic libertarian, John Stuart Mill, said:

The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others….Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.

Note the key phrase – the individual is sovereign! It runs smack against ideologies of collectivism, as well as the norms of a traditional, religious society. Josh Malihabadi had not studied philosophy or its history. Nor did he have a university degree. Quite probably, he had not read Mill. But being instinctively a rebel, Josh rediscovered and re-expressed in his own idiom the fundamental yearning of all humans to be free:

آفاق کی تنظیم پر اک طنزِ جلی ہے

اِس اَشہبِ ایّام کی ژولیدہ خرامی

ہٹ جاؤ سماوات، پلٹ جاؤ فرشتو!

انسان کو منظور نہیں طوقِ غلامی

Translation:

It is a taunt on the organization of this Universe

The tangled (confused) march of time

Move away heavens! Go back O angels!

Man does not accept chains of slavery

طنز … Sarcasm, satire, taunt اشہبِ ایّام۔ .. lit: The horse of (changing) days, metaphorically: the passage of time

ژولیدہ۔—tangled, confused, disorganized خرامی– gait, walk, running, (style of) movement

For Josh as a libertarian, what one eats, drinks, wears, or does in private is a matter of personal freedom and not for any state or society to decide or regulate. This is opposite to how our world actually works: heinous crimes frequently go unpunished but an individual may be pillorized, publicly humiliated, and stripped of dignity for actions that have harmed no other. Josh lashes out against this hypocrisy:

ہل چل روا، خروش روا، سنسنی روا

رشوت روا، فساد روا، رہزنی روا

االقصہ ہر وہ شے کہ ہے نا کردنی روا

انسان کے لہو کو پیو اذنِ عام ہے

انگور کی شراب کا پینا حرام ہے

(A rough translation: Insanity thrives, ill-will thrives, enmity thrives, chaos thrives, disorder thrives, rumoring thrives, bribery thrives, conflict thrives, theft thrives. In short, all that is bad does so splendidly well. Drink the blood of man and it matters but little. Drink wine from the grape and you are damned till eternity. )

What a brilliant encapsulation of our collective experiences! On the one hand, Pakistanis find themselves trapped with venal and kleptocratic political leaders who empty the public treasury again and again, and public servants and policemen who stuff their pockets. On the other side are hate-filled ideologues who stoke angry fires of faith; murders and massacres follow. Nevertheless, state and society pardon criminals but reserve their harshest punishments for innocents who merely exercise their right to personal choice.

The victims of this vile hypocrisy: the daughter who dares choose her mate instead of obeying her parents, the woman who seeks refuge from a brutal husband, the student who points out his teacher’s mistake in class, the young man who breaks from the stupefying traditions of his village, the university girl who dares to hold hands with her boyfriend, and the thinking person who sets aside the faith of his ancestors. They are hounded, beaten, defaced with sulphuric acid, whipped and paraded naked, jailed, and some have been thrown before ferocious dogs that ripped apart their flesh. An unending deluge of horrors flows whenever one opens the daily newspaper. Yet, while moralizers on television, and in places of worship, prattle endlessly about “sinful behavior”, they are silent about human suffering. In fact, they often gladly contribute to it.

The ongoing Talibanization of Pakistan is surely the antithesis of freedom, a crushing blow to the human spirit and a re-tribalization of society. Threatened more than all else is freedom for Pakistani women. In just one year there were 1400 reported honor killings. In much of rural Pakistan a woman is likely to be spat upon, beaten, or killed for being friendly to a man or even revealing her face. Newspaper readers expect – and get – a steady daily diet of stories about women raped, mutilated, or strangled to death by their fathers, husbands, and brothers. Energetic proselytizers like Farhat Hashmi, never once mentioning these recurring tragedies, have made deep inroads even into the urban middle and upper classes. Their emphasis is on covering women’s faces, putting women back into the home and kitchen, excluding them from public life, and destroying ideas of women’s equality with men. Female state officials have been shot and killed, and fatwas issued against others. A hypocritical society sinks to ever lower depths even as the collective piety increases by the day, and the faithful teem into mosques.

Oppression by tradition, custom, and religion is nothing new. But once upon a time, defiant messages of freedom – like Josh’s – could strongly resonate with the Pakistani public. Many will remember that powerful speech of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto – which bears an eerie similarity to the poem quoted earlier. Bhutto had lashed out against his mullah detractors in the 1970 elections saying: ha’an main sharab peeta hoon, logon ka khoon nahin peeta [Yes, I drink wine but not the blood of innocents]. The crowd roared approval. Bhutto won the first – and perhaps the only genuinely significant election – in Pakistan’s history. Tragically, he betrayed his electorate and reneged later on much of what he said he stood for. But, in the end, his capitulation to the mullahs and instituting Islamic laws did not save his neck. He died writhing at the end of a noose that he fashioned for himself.

Would Bhutto’s boldly defiant message – or something similar that violates today’s social norms – have the same effect today? Could it even be voiced? Unlikely! On the contrary, such a frank public admission would be suicide for any whisky-drinking military general or political leader. Unlike Bhutto, the new crop of leaders cannot take chances, being aware that within the Pakistani lower-middle and middle classes there now lurks a grim and humourless Saudi-inspired revivalist movement that cannot tolerate even a whiff of irreligiousity. Everyone knows that public figures – including Pakistan’s present and past presidents – cheat on their wealth declarations, do not pay their due share of taxes, rig elections, bribe judges, eliminate rivals, and place unqualified favorites into positions of power. But all is washed clean as they rush to perform Umrah several times a year in Saudi Arabia. Their unctuous piety is displayed in Ramzan with lavish fast-breaking iftar parties and taraveeh prayers. If any blemishes remain, they can always be wiped off with an extra Haj pilgrimage.

Who can deny that the times have changed? A transformed Pakistani culture now frowns upon every form of joyous expression, including the dance and music that had been a part of traditional Muslim life for centuries. Kathak dancing, once popular among the Muslim elite of India, has no teachers left in Pakistan. In Taliban controlled areas of the Frontier province, even the entirely male-performed Khattak dance has disappeared. Thousand year old statues are blown up, and education for girls declared haram. Lacking any positive connection to culture and knowledge, this new revivalism seeks to eliminate “corruption” by strictly regulating individual freedoms.

Meanwhile Pakistani urban elites, disconnected from the rest of the population, comfortably live their lives through their vicarious proximity to the West. Even the bearded ones lust for the “Green Card”. But on Fridays they don their prayer caps and drive their shiny new imported cars to their neighbourhood mosque. Rich but bored middle-aged housewives, whose only job is to manage a fleet of servants, go to Al-Huda centres and return clad in burqas. Their conversion to the Faith has been quick and expedient.

Those Pakistanis who consider their country morally superior to the West should be deeply ashamed that, while they burn churches and temples in their country, mosques and Islamic Centers flourish in America. There is no church in Saudi Arabia but new mosques are perennially under construction in the US and Britain. Do those who fulminate day and night in Pakistan against religious persecution of Muslims in the West ever reflect on this fact?

Words fail to describe recent horrors. In 2009 a frenzied mob of 20,000 Muslims went on a rampage against Christians in the town of Gojra in Punjab. They had been put into a state of madness by mullahs in madrassas and mosques, who fired them with the notion that a Christian man had destroyed a page of the Quran. The mob destroyed dozens of houses and burnt several Christians to death, including women and children. Of course, there is a long history of attacks against minorities in Pakistan and this was just one of very many. The entire village of Shantinagar had been destroyed by another Muslim crowd in 1997. Then there is the tragic story of a mill-worker who had been beaten to death near Gujranwala for eating at a restaurant in spite of a prominently displayed notice “No Christians Allowed”. Perhaps he thought that he could sneak in unnoticed. What is especially sad is that, in a protest demonstration by Christians in Islamabad against the Gojra massacre, there were no Muslims. The Pakistani media, knowing full well that it was lying, passed off the massacre as a “clash between two groups”.

Secular honesty has few followers in an age where hypocrisy is an accepted way of life. Deceit and theft are guarantors of prosperity in today’s Pakistan. Josh, the poet, cries out in a moral wilderness.

Josh Was Anti-Imperialist Yet Pro-Modern

At the crack of dawn on 23 March 1931, the twenty four year old revolutionary Bhagat Singh, together with his two colleagues Sukh Dev and Raj Guru, were hanged until pronounced dead. They had courted arrest after throwing bombs – which did not cause casualties – to protest the British occupation of India. Specifically, they had expressed their opposition to the visit of the Simons Commission. Charged with determining the quantum of freedom allowable to the natives, the Commission had no Indian members. Widespread public protests had had no effect upon the court’s decision to award capital punishment to the three revolutionaries.

A sorrowing Josh composed a poem which he read out in the same city, not far from where the three young men had been executed:

سنو اے بستگانِ زلفِ گیتی ندا کیا آرہی ہے آسماں سے

کہ آزادی کا اک لمحہ ہے بہتر غلامی کی حیاتِ جاوداں سے

(A rough translation: Hear this all who care for life and love in this world. A voice speaks from the sky. That a moment of freedom is better than a life of slavery.)

Josh’s admiration for Bhagat Singh was not merely because this young man was a fighter, but also because he was a free-thinker and atheist. With a keen sense of history and commitment to his goals, Bhagat Singh had educated himself in matters of society and politics before picking up the gun. In this he differed from most others engaged in fighting the British who had thought little about the likely contours of a post-independence society.

For Josh, a Muslim, the fact that Bhagat Singh was a Sikh was irrelevant. What mattered was the inherent injustice of being ruled from afar, and the violent oppression of the colonizers. Even as they prepared for an eventual exit, a class of sycophants was assiduously cultivated by the British. They would remain as instruments for colonial domination, rule from afar. Josh thunders against this elite, who had donned the mantle of their former masters:

برطانیہ کے خاص غلامانِ خانہ ساز

دیتے تھے لا ٹھیوں سے جو حُبِّ وطن کی داد

جِن کی ہر ایک ضرب ہے اب تک سروں کو یاد

وہ آئی سی ایس اب بھی ہیں خوش وقت و با مراد

شیطان ایک رات میں انسان بن گئے

جتنے نمک حرام تھے کپتان بن گئے

(Rough translation: These special friends of the British. Whose cudgels had rained upon us blow after blow. Blows, that our still-aching heads cannot forget. Yet today they thrive and thrive. In a flash devils have turned into angels. They are now the captains of our ship of destiny)

Josh’s clear-headed, secular thinking was not shared by most Indians, Muslim or Hindu. Religious reasons competed with secular ones for fighting the British. The “Sepoy Mutiny” of 1857 was triggered when the British introduced new rifle cartridges rumored to be greased with oil made from the fat of animals. The fat of cows was taboo to Hindus while Muslims protested the pig fat. Although Muslims had suffered more than Hindus, they tended to oppose the British for religious reasons more than Hindus.

The reason goes back into history. Although colonization had hit all native peoples hard, it left Muslims in India relatively more disoriented and confused than Hindus or Sikhs. Three hundred years earlier, the development of modern science in the West had led to the emergence of a capitalist order that provided the impetus to forcibly expand Western access to markets and sources of raw materials. Conquest by forces from across the oceans changed forever the comfortable world of India’s Muslims who had dominated India for a thousand years. The establishment of British dominion during the 18th and 19th centuries dealt a death blow to the Moghul empire. Elsewhere, Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 led to a series of changes that ended with the break-up of the Ottoman empire, the last of the great Muslim empires.

European countries colonized virtually all the Muslim world from East Asia to West Africa. A mercantilist and industrializing Western metropolis was on the ascendancy. The old Indian order gasped and then died, unable to withstand the forces unleashed by Scientific Revolution. Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Moghul emperor, vengefully blinded by the British, spent his last days in captivity. He wrote beautiful Urdu poetry which many people have on their lips even today. But he stood for little besides a decadent monarchy and an order of things that could offer little to the people of India.

The brutalization of a pre-scientific native people by scientifically minded colonists drew a variety of responses ranging from cooptation and despair, to non-cooperation and resistance. Humiliation and helplessness, and a deep sense of resentment, made it difficult for most to see the diversity of the West and its great achievements of the Enlightenment. In any case, the orthodoxy had little use for scientific rationality and democratic pluralism. For them, the farangees (foreigners) were simply kafirs.

The anti-farangee movement amidst the Muslim religious orthodoxy was centred around Deoband, a town in northern India. The Deoband madrassa operated under the slogan that Islam was in danger. Established nine years after the 1857 uprising, it set itself the task of training Islamic revolutionaries who would fight the British; today Pakistani Deoband ulema provide the ideological basis for the Taliban in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Deoband school became particularly active in demanding the restoration of the caliphate, which had been eliminated by Kamal Ataturk in 1924.Under Maulana Mahmud ul-Hasan and Maulana Husain Ahmad Madni, Deobandis were politically radical, but the movement was socially conservative. Their goal mission was to preserve traditional Islamic learning and culture.

Although it was strongly opposed by the Deobandis, a movement of Muslim modernists emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century. Centering around Syed Ahmad Khan, it sought acceptability for an interpretation of Islam consistent with science and reason. The Muslim elite expanded its educational horizon by allowing its children to study the English language, science, and other secular subjects. Nevertheless, the bulk of Indian Muslims remained rooted in the past and education remained confined to religious subjects for the Muslim masses. The maulanas of Bengal, like the Deobandis of Uttar Pradesh, were adamantly opposed to secular education. In 1835 they collected 8000 signatures against the education reforms proposed by Lord Macaulay, a member of the Supreme Council of India. But these very reforms had been welcomed by the Hindus of Bengal who earnestly supplicated the British for still more schools and colleges. These supplications earned them the contempt of Muslim leaders, who charged that they were sucking up to the rulers.

Muslim conservatism in education was to have grave consequences for Muslim societies everywhere. In the 21st century the results of this resistance are evident: India stands at the threshold of being a major technological and economic power while Pakistan remains mired in the backwaters. Pakistan’s is being devastated by an Islamic resurgence in the form of Talibanization which, as it gains further ground, threatens to send its people back to the darkest of ages.

In those times, could one have been for progress and yet have been fighting against colonialism? Josh Malihabadi, like other secular Muslim Indian nationalists, thought this was certainly possible. British rule had to be resisted because it was coercive, unequal, and discriminatory even if it had brought elements of the Enlightenment with it. He therefore hated using the English language. But, a half-century before Josh was born, Muslim progressives had already been deeply divided on these questions. For example, Jamaluddin Afghani had sought to bring scientific enlightenment to Muslims while also energetically seeking to overthrow colonial rule across the Muslim world. But he was at loggerheads with another forward-looking contemporary, Syed Ahmad Khan, who had firmly allied himself and his Muslim followers with India’s masters, and wanted Muslims to learn science and English. Nevertheless, Afghani and Syed Ahmad agreed on one central point – they both saw traditional cultures as having run their course and now out of steam. They knew that the obstacle to social, cultural, and economic progress was not imperial occupation alone, but also fossilized thought rooted in ancient times.

Josh’s position is probably closer to Afghani’s rather than Syed Ahmad Khan’s. He was against the British – and the English language – but he reserved his strongest attacks against tradition and culture as instruments of mental enslavement. His rhythmically fascinating poem, murdo’on ki dhoom , or, “The Cacophony of the Dead” is a powerful blow against the fossilization of thought:

مخلوق کو دیوانہ بنائے ہوئے مُردے

یاروں کے دماغوں کو چُرائے ہوئے مردے

اوہام کے طوفان اُٹھائے ہوئے مُردے

عقلوں کو مزاروں پہ چڑھائے ہوئے مردے

آفاق کو سر پر ہیں اُٹھائے ہوئے مردے

دیکھو کہ ہیں کیا دھوم مچائے ہوئے مردے

(A rough translation: The dead drive our people mad. The dead steal the minds of the living. The dead unleash mighty storms of superstitions. Our minds are trapped in tombs and morgues. The sky too belongs to the dead. Look! Listen to the cacophony of the dead!)

In this poem, Josh speaks equally to Hindus and Muslims, city elites and rural poor, educated and illiterate. Held down firmly by the dead hand of belief and tradition, they drown in superstition and illogic. They pray for rain, attribute earthquakes to the wrath of god, think supplications to heaven will cure the sick, seek holy waters that will absolve sin, look to the stars for a propitious time to marry, sacrifice black goats in the hope that the life of a loved one will be spared, recite certain religious verses as a cure for insanity, think airliners can be prevented from crashing by a special prayer, and believe that mysterious supernatural beings stalk the earth. These superstitions hold as much today as they did decades ago.

The bizarre illogic sometimes boggles the mind. For example, India’s 1998 nuclear tests were preceded by serious concern over the safety of cattle at the Pokharan test site. Former Indian foreign minister Jaswant Singh writes “For the team at the test site – which included A. P. J. Kalam, then the head of the Defence Research and Development Organisation – possibly death or injury to cattle was just not acceptable.” India aspires to being a world power, but no Indian politician today can suggest that cows can be eaten. No politician in Pakistan dare suggest that praying for rain won’t work. Yet, these neoliths have nuclear science and both countries can annihilate each other in a matter of minutes.

The Cacophony of the Dead continues:

لیلاے تفکُّر کو سنورنے نہیں دیں گے

دریاے توہّم کو اُترنے نہیں دیں گے

تحقیق کی نبضوں کو اُبھرنے نہیں دیں گے

تقلید کا شیرازہ بکھرنے نہیں دیں گے

اِس بات کا بیڑہ ہیں اُٹھائے ہوئے مُردے

دیکھو کہ ہیں کیا دھوم مچائے ہوئے مردے

(A rough translation: The dead will not let reason flower. They will not block flowing rivers of superstitions. They will not let minds question and research. They will not allow blind belief to be challenged. But they certainly do ensure that nothing changes. Look! Listen to the cacophony of the dead!)

Deeply conscious of the calamitous decline in the intellectual energy of Muslims since the Golden Age of Islam, Josh wondered aloud at the causes. What caused a wonderfully alive and intellectually productive civilization to falter, then collapse? Allama Muhammad Iqbal, who is Pakistan’s national poet, in his epic dialogue with God (shikwa and jawab-e-shikwa) saw the straying of Muslims from the True Path of the Quran as the reason. But Josh adopts the diametrically opposite path of the “Muatizilla” tradition of Muslim rationalist philosophers.

The dominance of the Muatizilla over long periods of time between the 9th and 13th centuries accounts for practically all of Islamic scientific progress in those times. Their ultimate defeat – marked by bloodshed and persecution – marked the end of Islam’s Golden Age. The Muatizilla, who battled their Ashari adversaries on the central issue of freewill versus pre-destiny, believed that Allah had empowered man with the power of reason, the use of which could lead him to choose between alternatives.

The contrary opinion – that of the traditionalists – was that Man was a mere creature of fate, an irrelevance in the greater scheme of things. A straw in the wind, he could be blown hither and thither. All had been predetermined; it was useless to struggle against destiny. Therefore, supplicate Allah and heed his Book; that is the best that can be done.

Striking hard against this notion of helplessness, Josh’s Aadmi Nama (In the Name of Man) is a paean of extraordinary eloquence to the powers of Man:

اے نگاہِ مولویِ معنوی

دیکھ سوئے عزّ و جاہِ آدمی

آدمی ہے بوئے گُل رنگِ حنا

موجِ کوثر، موجِ مے، موجِ غِنا[i]

(Rough translation: Look and listen, o’ revered mullah. Look at Man’s dignity and grace. Man is the flower of life’s essence. Man gives color to this world, meaning to its existence, waters the arid desert, creates the wealth of the universe. )

Josh’s attack is head-on, without hesitation or apology. His poetic eloquence pushes him deep into dangerous territory. Perhaps, some might argue, a bit too far. Aadmi Nama continues:

د ستِ آدم، بُت تراش و بُت نما

نطقِ انساں، موجدِ حرفِ خدا

وہمِ انساں۔ بانیِٔ لات ومنات

فہمِ انساں، شارعِ ذات و صفات

ذہنِ انساں، پا بجولاں سوئے ذات

درکِ انساں، ہادمِ قصرِ صفات

آدمی کہسارِ ظن، قطبِ یقیں

آدمی پروردگارِ کُفر و دیں

آدمی دانائے اسباب و علل

فاتحِ مستقبل، دیوِ اجل

(A rough translation: With his hand Man fashions idols and images. With the power of words he creates the gods. With his superstition he makes the angels. With his intelligence he discovers qualities of the mind. With his mind he walks towards understanding himself. With his understanding he finds the house of knowledge. Man, source of knowledge and worthy of knowing. Man, creator of belief and disbelief. Man, who knows of cause and effect. Man, who shall one day win over death.)

But where did Man come from? Josh was an unabashed believer in the processes of physical law which have produced the wonders of nature culminating in the most wonderful of them all – the human race:

زندگی سعیِٔبلیغِارتقا کا ناز ہے

آب و آتش کی کرامت، خاک کا اعجاز ہے

(Rough translation: Life is the proud result of Evolution. Life is a gift of water and fire, the miracle of earth and dust.)

While other poets – Ghalib, most notably – have sniped from the sides, Josh declares open war on blind belief. His opponents screamed: Idolator! Worshipper of man! But little happened because Josh was an old man when died, his poems were little understood, and he had certainly lived in better times. One wonders: were he alive today, would he still be able or willing to write these lines? Most probably this poet would have been ripped to shreds by a shrieking mob, perhaps like the ones which burnt churches in Shantinagar and Gojra, or that in Shabqadar which had chased a terrified Ahmadi up a tree and shot him as he pleaded for his life.

Nationalism, Religion, Language: The Fatal Triangle

Every reader of this essay almost certainly carries a passport: Pakistani, Indian, Canadian, American, or whatever. Our world is presently divided into nations, which we tend to think of as permanent entities while forgetting how utterly recent they are. The League of Nations in the 1930’s had a maximum of 58 members. This is less than one third of the current 192 members of the United Nations. In other words, about 80 years ago, two thirds of the world’s current nation-states did not exist.

Even the oldest nation-state is but a few centuries old. I will not take sides in the academic debate of whether Peace in Westphalia, signed in 1648, actually marked the beginning of the first sovereign state. But much before that – fifty thousand years ago or more – our hunter-gatherer ancestors lived in tribes. Loyalty to the tribe was natural, a necessary condition for collective survival. Tribal markers – tattoos, piercings, bones through the nose or ears, binding of feet, dances and songs, giving particular names to children, festivals, marriage rules – were bonding elements because they identified who belonged to which tribe. Attachment to one’s tribe was unequivocal and total: the tribe could never be wrong. The individual did not matter, and must be ready to kill or die for the tribe.

Nationalism emerged as an advanced form of tribalism. In Europe, the invention of cannons, roads, and printing presses had made domains of control larger. Coalescing tribes, and larger tribes, could do better than fragmented ones. The notion of a nation slowly emerged. It built upon the myth of a common ancestry, reinforced by similarities of physiognomy, language, culture, or religion. The nation was seen as marching together towards some shared future destiny, and hence that it must work together. This strengthened its capacity to cope with the challenges of a hostile environment, and to compete successfully with other groups animated by similar beliefs.

But there is a downside to nationalism. Wired for “group think”, humans tend to assume that their particular group or nation has no peer or rival. However, since obviously not every nation can be the best of nations, this assumption simply has to be wrong. If it was just a harmless assumption who would care? On the other hand, when one group insists on its absolute superiority, there is high risk because the other is automatically reduced to an inferior position. My nation, the true patriot asserts, is better than your nation. We are spiritually pure, you are intrinsically corrupt. Nationalism can then become the justification for mass murder and genocide.

This is why Einstein called “nationalism an infantile disease, the measles of humanity”, and Erich Fromm declared that “nationalism is our form of incest, is our idolatry, is our insanity”, and that, “patriotism is its cult”. Einstein and Fromm both, of course, were Europeans.

Europe, which invented nationalism in the Age of Enlightenment, has suffered more than any other part of the world from nationalism, which soon spun out of control. The two world wars left 70-80 million dead, and many times more permanently disabled. The lessons of Europe must, therefore, be carefully studied by people from Pakistan and India.

It is interesting to see how nationalism laid out its roots in Europe. For example, in the 17th and 18th centuries, French culture had imposed itself on many parts of the European continent. Frederick the Great of Prussia and his court spoke and wrote in French, but they really thought of themselves as Germans. Indeed, a nascent German nationalism was beginning to stir. Even before the establishment of a German national state, the romantic German nationalist, J.D. Herder, wrote a poem in protest against the French culture of Frederick’s court in Prussia:

Look at other nationalities!

Do they wander about

So that nowhere in the world they are strangers

Except to themselves?

They regard foreign countries with proud disdain.

And you, German, alone, returning from abroad,

Wouldst greet your mother in French?

Oh spew it out before your door!

Spew out the ugly slime of the Seine!

Speak German, O you German!

About two hundred years later, Konrad Lorenz, the Austrian Nobel-Prize winning zoologist and ornithologist, studied animal traits. But he also explored the biological roots of human aggression. Living in pre-WW II times, he warned against the growing German nationalism:

“We have seen on the screen the radiant love of the Fuhrer on the faces of the Hitler Youth… They are transfixed with love, like monks in ecstasy on religious paintings. The sound of the nation’s anthem, the sight of its proud flag, makes you feel part of a wonderfully loving community. The fanatic is prepared to lay down his life for the object of his worship, as the lover is prepared to die for his idol.”

Konrad observed that men may enjoy the feeling of absolute righteousness even while they commit the worst atrocities. Indeed, in situations of war, conceptual thought and moral responsibility descend to their lowest ebb. My revered physicist colleague from Denmark, Dr. John Avery, in his remarkable book “Space-Age Science and Stone-Age Politics”, (translated into Urdu and freely available at www.mashalbooks.com) quotes a Ukranian proverb that says: “When the banner is unfurled, all reason is in the trumpet”. Thereafter, men stop being human and turn into killing machines.

In South Asia, as in Europe, tribalism is generally considered to be on the retreat. But, perhaps paradoxically, in large parts of Pakistan it has been enhanced by technology and protected by modern weapons which tribal people can easily acquire from the developed world. Whether urbanization will create a melting pot, or temporarily lead to a re-solidification of ethnic and linguistic boundaries that will re-tribalize society, is an open question. But the appeal to a larger entity will surely win here too at some point in the future.

The enormous power latent in nationalism was revealed in 1947 yet again. Nationalism dovetailed with religion to create ab-initio the first Islamic nation-state in history, Pakistan. This world-shaking event posed a fascinating paradox: major Muslim political parties, such as the Jamaat-e-Islami and the Jamiat-e-Ulama-e-Hind, fiercely opposed the creation of a Muslim nation state. Nevertheless, the personally secular Mohammed Ali Jinnah captured the Muslim mood with his “Two-Nation Theory”.

In his 1940 presidential address delivered in Lahore, Mr. Jinnah asserted that Muslims and Hindus were two separate peoples who had separate customs, histories, heroes, and outlooks. Thus they belonged to two separate streams of humanity that could never intermingle nor live in peace together. Without this core belief, there would not have been a Pakistan. Mr. Jinnah assumed as a matter of course that Muslims – by virtue of sharing a common faith – could live together harmoniously and they naturally constituted a nation.

The strength of Mr. Jinnah’s Muslim League in the Muslim-majority provinces of India was put to the test during the 1945-46 election campaign. Consequently in the public meetings and mass contact campaigns the Muslim League openly employed Islamic sentiments, slogans and heroic themes to rouse the masses. This is stated in the fortnightly confidential report of 22 February 1946 sent to Viceroy Wavell by the Punjab Governor Sir Bertrand Glancy:

The ML (Muslim League) orators are becoming increasingly fanatical in their speeches. Maulvis (clerics) and Pirs (spiritual masters) and students travel all round the Province and preach that those who fail to vote for the League candidates will cease to be Muslims; their marriages will no longer be valid and they will be entirely excommunicated… It is not easy to foresee what the results of the elections will be. But there seems little doubt the Muslim League, thanks to the ruthless methods by which they have pursued their campaign of “Islam in danger” will considerably increase the number of their seats….

When Mr. Jinnah finally succeeded in creating Pakistan, Josh’s reaction to the partition of India was one of dismay. His rubayi “Mourning Independence” (Matam-e-Azadi) was written in India in 1948 and Josh recited it to a public gathering in front of Delhi’s Red Fort on India’s first Independence Day:

اے ہمنشیں ! فسانۂ ہندوستاں نہ پوچھ

روداد جام بخشیِٔ پیرِ مغاں نہ پوچھ

بربط سے کیوں بلند ہوئی ہے فغاں نہ پوچھ[ii]

کیوں باغ پر محیط ہے ابرِ خزاں نہ پوچھ

کیا کیا نہ گل کھلے روشِ فیضِ عام سے

کانٹے پڑے زبان میں پھولوں کے نام سے

(A rough translation: Blame me not for the sorry tale of Hindustan. Blame not the seller of wine if it produced no joy. Nor blame the musical instrument for producing mere discordant noise. A cold autumn rain falls on the garden. Those beautiful roses that could have grown will grow no more. Thorns there shall now be many, flowers no more. )

By now the carnage of Partition had already occurred. Neighbor turned against neighbor, friend against friend. A frenzy of blood letting, murder, arson and rape enveloped the cities, towns, and villages of India. Hindus and Sikhs slaughtered Muslims, and Muslims slaughtered Hindus and Sikhs. Trains filled with corpses arrived at railway stations in Lahore and Amritsar, on opposite sides of the newly established border. A mass transfer of population left a million people dead in one of the most catastrophic events of the 20th century. Even today that bitterness is far from gone.

Josh could find no reason to be joyful:

ابھرے تو جوش بادہ گساراں نہیں رہا

بادل گھرے تو رنگِ بہاراں نہیں رہا

باتیں کھلیں تو رقصِ نگاراں نہیں رہا

بوتل کھلی تو مجمعِ یاراں نہیں رہا

کوئی سبیلِ بادہ پرستی نہیں رہی

مستی کی رات آئی تو مستی نہیں رہی

(A rough translation: Little good does this wine bring. Spring comes without its bright colors. Conversations are limp and lifeless. Even the wine brings little cheer. Drink as much as you want but it still does not help. The night of our celebration is dark and joyless.)

Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister of India, who was present in the audience, was visibly unhappy with the poem, but then listened to it again in a private gathering. He is said to have protested that Josh should not have read it in front of the general public, to which Josh curtly retorted “but it was meant for them”[iii].

Among Josh’s most brilliant and hard-hitting poems, one must certainly include Zindaan-e-Musulus: Lasaan, Adyan, Autan (The Triangular Prison: Language, Religion, Nation). Some excerpts follow:

کب تک رہیں گے آخر یہ طنطنے ، یہ تیور

یہ تیر ، یہ کمانیں، یہ نیمچے، یہ نشتر

یہ آدمی ، یہ شاہِ آفاق و میرِ دوراں

نکلے گا کب حصار ِ جغرافیہ سے باہر

(A rough translation: How long shall this pomp and façade last? These bows and arrows, these knives and daggers? Man, who presides over the universe, the king of our times. When shall he escape the narrow confines of geography? )

The essence of the last line above is the concept of territoriality. This is so universal and commonplace that it is simply taken for granted. Individuals internalize territorial dominance as part of the formation of a personal identity. Now an established concept in social ethology, territoriality was once a survival imperative. Like their ape ancestors, humans had to compete for resources necessary for the individual or group. Boundaries had to be defined. Some territorial mammals use scents secreted from special glands, to create their demarcations. Dogs and cats establish their territories using scent-marks, but also through urination or defecation. Humans draw maps.

Shall these boundaries remain until eternity? Josh answers:

کب تک بنے رہوگے اے وارثانِ آدم

اپنوں میں آبِ کوثر، غیروں میں تابِ خنجر

یہ ’غیر‘ کا تصورِ افلاس آگہی ہے

رہتے نہیں ہیں پیارے ’اغیار‘ اس زمیں پر

مشرق سے تا بہ مغرب، اک نسل، اک نسب ہے

اس آسماں کے نیچے، اور اس زمیں کے اوپر

قوموں میں بانٹتا ہے جو نسلِ آدمی کو

مشرک ہے اور کافر، کافر ہے بلکہ اکفر

(A rough translation: O’ descendant and inheritor of Adam. Until when shall you want peace for yourself and a dagger for others? This notion of the “other” is so primitive. Remember, my friend, there are no “others” on this earth. From east to west we are all one species, one race. All under this sky and upon this earth are the same. Some work to split us into nations. They play God and are kafirs. Nay! They are not kafirs but the most sinful of kafirs! )

In decrying nationalism, Josh could be equally speaking to Americans who have waged dozens of wars in the last century, invaded countries, dropped atom bombs, leveled cities, starved populations and tortured prisoners. Or he could be addressing the Japanese who today are a peaceful nation. But in 1937 they murdered hundreds of thousands of Chinese and raped between 20,000-80,000 women in one of the worst episodes of human brutality. It is hard to imagine that the Turks, who are almost integrated into Europe, could have slaughtered 100,000-200,000 Armenians. The list goes on.

It is a depressing fact that today, in a world shrunk by internet and mass communication, we still live in nation-states for which people feel intense emotions of loyalty very similar to the tribal emotions of our cave-dwelling ancestors. Tsunamis of patriotism have again and again brought forth millions of patriots anxious to slaughter those on the other side. Somehow the ape within us refuses to go away.

So should one love the country one was born in? Hate it and love another? George Monbiot, a British citizen and columnist for the Guardian, states his position:

I don’t hate Britain, and I am not ashamed of my nationality, but I have no idea why I should love this country more than any other. There are some things I like about it and some things I don’t, and the same goes for everywhere else I’ve visited. To become a patriot is to lie to yourself, to tell yourself that whatever good you might perceive abroad, your own country is, on balance, better than the others. It is impossible to reconcile this with either the evidence of your own eyes or a belief in the equality of humankind. Patriotism of the kind Orwell demanded in 1940 is necessary only to confront the patriotism of other people: the Second World War, which demanded that the British close ranks, could not have happened if Hitler hadn’t exploited the national allegiance of the Germans. The world will be a happier and safer place when we stop putting our own countries first.

The Lessons for Pakistan

This has been a long essay. What should right-minded Pakistanis conclude from the many themes of Josh’s radical, progressive, secular poetry?

At the outset, the reader must recognize that, contrary to what the doomsayers have announced many times in recent months, Pakistan is a nation-state that is not going to go away. But, if it is to be a happy nation, it needs a positive vision. What should that new vision be?

Certainly, Pakistan would not have come into existence but for the fear of Hindu domination. Fortunately, there is now no reasonable basis for this fear. Hence, there is no need for any further two-nation, three-nation, or multi-nation hypotheses. Pakistan and India are not going to become one country any time in the foreseeable future. Except for a few Shiv Sena crackpots in India, no Indian wants re-unification while Pakistanis would be even more allergic to the idea. Therefore one must get the notion of unification firmly out of the way. Instead, Pakistan must aim towards becoming a normal civilized country, where people live normal, happy lives free of needless prejudice. How should it go about seeking this?

A pluralist democracy is the answer. For sixty years we have feared diversity and insisted on unity. But Pakistan paid a very heavy price because our leaders could not understand that a heterogeneous population can live together only if differences are respected. The imposition of Urdu upon Bengal in 1948 was a tragic mistake, and the first of a sequence of missteps that led up to 1971 – which left the Two-Nation theory in tatters. The faith-based Objectives Resolution of March 12, 1949 has been just as big a disaster for Pakistan because it led to the disenfranchisement of its citizens, and ignored the principle of respecting diversity.

Pakistan is a multi-ethnic, multi-national state – and it must be recognized as such. Its four provinces have different histories, class and societal structures, climates, and natural resources. Within them live Sunnis, Shias, Bohris, Ismailis, Ahmadis, Zikris, Hindus, Christians, and Parsis. Then there are tribal and caste divisions which are far too numerous to mention. These cannot be wished away. Add to this all the different languages and customs as well as different modes of worship, rituals, and holy figures. Given this enormous diversity, Pakistani liberals like to speak for “tolerance”. But this a bad choice of words. Tolerance merely says that you are nice enough to put up with a bad thing. Instead, let us accept and even celebrate the differences! Inclusion, not exclusion, must be the new principle. We must learn to accept, and even celebrate, our differences and diversity. Other countries that are even more diverse than Pakistan have learned how to deal with this successfully. So can Pakistan.

Pakistan must – and can – find a new identity without insisting that every Pakistani be a Muslim. Today almost every Pakistani understands Urdu, which was not true 60 years ago. This is a hint that a new Pakistani identity is in the process of formation. Even if they don’t always like each other, Pakistanis are learning to understand and deal with each other simply by virtue of having had to live together long enough. And so, unless things fall apart because of the irresponsibility of its rulers, Pakistan will surely become a nation one day – even if it wasn’t one to start with.

The future: much depends upon how we deal with Baluchistan. I definitely do not approve of the desire of some Baluchis who want to secede from Pakistan. It is not practical, nor realistic, nor in the interests of the Baluch. Remember, Baluchistan is not East Pakistan; it is part of the same land mass. Baluch, Sindhis, Punjabis, and Pathans must somehow learn to live together. Baluch anger at being cut away from the riches that lie beneath their ground is perfectly justifiable. They are the poorest in Pakistan in spite of being hugely rich in terms of mineral deposits and oil. A formula must be worked out that will appropriately benefit the people of Baluchistan rather than their tribal sardars. Those in Islamabad need to do more.

Still more depends on how we plan to deal with economic inequity. Pakistan has never had land reform, imposes no agricultural tax, rewards feudal lords with seats in parliament, and its institutions empower the rich at the expense of the poor. The landscape is that of conspicuous consumption and abject poverty.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the new vision of Pakistan demands that it renounce religious discrimination and care equally and deeply for all citizens. All the myriad sects of Sunni and Shia Islam must be considered equals. The state must care just as much for its Hindus, Christians, or Ahmadis. This must hold even for the odd Pakistani Jew – although I don’t think there is any left (there were a few Jews during my school days in Karachi but they all left).

Resting all matters of the state upon religion is a prescription for unending fratricidal struggles. This will continue to pit faithful Muslims against other faithful Muslims. Parachinar and Hangu have been ablaze for years, car bombs still continue to explode in Baghdad even after the Americans have announced their withdrawal, and similar slaughters happen around the globe. The very fact that there is serious disagreement even among believers of the same faith – not to speak of faiths hostile to each other – means that there cannot be only one single truth in any religion, or agreement on how to run a religious state.

For this reason, Pakistan, as a country with many Muslim sects cannot be run by the sharia because, even for Muslims, the obvious question is: whose sharia? Shafi’i, Hanafi, Maliki? Hanbali? And what about the Shias who accept none of these? These questions cannot be pretended away. They have not been resolved in a thousand years. Nor can they be resolved in the next thousand. It is time to move religion out of politics.

This calls for constitutional reform. Pakistan cannot afford a constitution that discriminates between Muslim and non-Muslim. Therefore every law that discriminates between the citizens of this land must be annulled. Every citizen of Pakistan needs to be declared exactly equal to any other irrespective of religion, ethnicity, or class. We clearly cannot impose jizya on non-Muslims and expect loyalty from them. Thus the law must be secular to be uniform.

Further, if we want unity in the face of diversity, then the majority must stop trying to force itself upon the minorities. Most crucially, the state must stop acting on behalf of the majority.

To conclude, sixty years is not a long time in the life of a nation, but it is time enough to learn from grievous mistakes. As times change, needs change. Slogans and mottos, and the avowed national purpose, should also change. Surely, every nation-state in the world stands somewhere along a learning curve.

Time is running out for Pakistan so the learning will have to be quick. Narrowness of vision has made this into a land of suicide bombers. Shredded bodies and twisted limbs lie all around. So let us harken back to Josh Malihabadi’s clarion call as he pleads for a new global consciousness welding all humans together.

His message rings loud and clear:

کِس کھوہ میں ہے آخر تیرا خطیبِ اعظم

اےراستی کی محراب، اے روشنی کے منبر

ہاں وحدتِ خدا کا اعلان ہو چکا ہے

اب وحدتِ بشر کا، دینا کوئی پیمبر

(A rough translation: Why are our great preachers silent? They speak of righteousness and illumination by faith. They have announced that God is one. But shall they now announce a new prophet who says humanity is one? )

Acknowledgements

My interest in the poetry of Josh Malihabadi was stimulated by my participation as a speaker in a symposium organized in Calgary, Canada by Iqbal Haider, founder of the Josh Literary Society. In listening to the other speakers, I found myself entranced by the richness and beauty of the poetry which hitherto I had only been casually aware of. I am also grateful for various pieces of information about Josh’s life and work that I received from Mr. Haider. These were important in giving this essay its final form, leading to its publication in A Conjugation of Art and Science (2014, Amazon Books, ed. Iqbal Haider). In revising this essay, I am happy to acknowledge Syed-Mohsin Naquvi for his detailed comments, and thank him for typing the couplets in Urdu-nastaliq script as well as correcting a translation. And, finally, I acknowledge Sadia Manzoor for unpaid proofing of the final manuscript.

(By arrangement with Eqbal Ahmad Centre for Public Education: http://eacpe.org/)

[i] A wave of music

[ii] Don’t ask why the harp sings a wailing tone

[iii] I am grateful to Iqbal Haider for this anecdote.

Source: