A profile of Sheikh Nimr by The New York Times

BAGHDAD — In 2008, an American diplomat traveled to a poor village in eastern Saudi Arabia to visit a thin, bearded preacher who was known for criticizing the government and wrote him off as “a secondary player in local politics,” according to a report on the visit released by WikiLeaks.

Years later, that preacher, Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, fueled a protest movement with his virulent sermons excoriating the Saudi royal family.

On Saturday, Saudi Arabia executed him on terrorism charges, leading to the collapse of relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran and solidifying Sheikh Nimr’s status as a potent international symbol of Shiite opposition to the Saudi monarchy.

The rise to prominence of Sheikh Nimr, who was scarcely known outside of Saudi Arabia before his arrest in 2012, corresponds closely with the intensification of the strategic and sectarian rivalry between Shiite Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia that has put them on opposing sides of conflicts across the region.

For Iran and its allies, Sheikh Nimr was a valuable domestic antagonist to the Saudi ruling family, and they adopted his cause and amplified it in their news media. For Saudi leaders, Sheikh Nimr was a dangerous dissident who personified deep-seated fears of Iranian meddling inside the kingdom’s borders.

Saudi Arabia arrested Sheikh Nimr in 2012 and later sentenced him to death for charges that included breaking allegiance with the ruler, inciting sectarian strife and supporting rioting and destruction of property during protests, according to Human Rights Watch. He was killed in a mass execution with 46 other prisoners, most of them linked to Al Qaeda.

Many Saudis defended that pairing of crimes.

“We are speaking of a terrorist person,” said Salman al-Ansari, a Saudi commentator provided by the Podesta Group, a public relations firm working for the Saudi government.

Mr. Ansari accused Sheikh Nimr, who was in his mid-50s, of organizing a “terrorist network” in Shiite areas in eastern Saudi Arabia and compared him to a Qaeda ideologue who sanctioned the killing of security forces.

Others, however, note that for a preacher whose hatred for the royal family is easy to find on YouTube, examples of him calling for violence are not. The Saudi government has not made public evidence it may have against him.

The government had faced increasing pressure inside the country to execute the Qaeda figures, all Sunnis, who had been sentenced for deadly attacks in the kingdom about a decade ago. The government also likely figured that a mass execution would deter sympathizers of the Islamic State jihadist group, which has declared the kingdom an enemy and repeatedly attacked it.

Yet some Western analysts say the government could have faced domestic blowback if it had executed only Sunnis, while sparing Shiites accused of participating in violence that took the lives of police officers. Three other Shiites were executed along with Sheikh Nimr.

Others, however, say Sheikh Nimr was punished for publicly questioning the legitimacy of the royal family and to send a message to other dissidents.

“He was convicted for stuff he said; there is no other way of putting it,” said Toby Matthiesen, senior research fellow at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, and the author of a book on Saudi Shiites.

Sheikh Nimr was from the village of Awamiya in eastern Saudi Arabia, where most of the kingdom’s Shiite minority lives. The Shiites, who make up about 10 percent of the country’s 20 million citizens, have long complained of discrimination by the state and of defamation of their beliefs by state-sanctioned clerics.

Sheikh Nimr’s family and village were known for their opposition to the monarchy, a tradition he embraced after returning home from more than a decade abroad for religious studies in Iran and Syria.

He was not a noted scholar, but called for greater rights for Shiites — and with limited results, since many avoided his fiery sermons.

In 2008, a public call he made for the formation of a “Righteous Opposition Front” to represent Shiites fell flat. A diplomatic cable on the event said there had been “no discernible support for the Sheikh’s comments.”

His domestic profile grew in 2009, when he spoke out on behalf of Shiite pilgrims who had clashed with security forces over access to a site in the holy city of Medina. He went into hiding, fearing arrest, and his influence waned. In 2010, an American diplomatic cable quoted a community leader as saying Sheikh Nimr “spoke out too strongly,” which led to his “losing credibility and his following.”

That changed with the outbreak of the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011, when young Shiites in eastern Saudi Arabia and nearby Bahrain joined the protest movement sweeping the region and were soon clashing with security forces in both countries.

Demonstrators who dismissed their leaders’ careful efforts to win concessions from the Sunni rulers embraced Sheikh Nimr, who preached in simple language brimming with anger. He said that Saudi Shiites should get their fair share of the country’s oil and even suggested that they could secede.

“He said all the things that the young people wanted to hear but that the other leaders didn’t want to say,” Mr. Matthiesen said.

In one sermon, he spoke out against “oppressors,” Sunni or Shiite, and called for the oppressed to unite against them.

“In any place he rules — Bahrain, here, in Yemen, in Egypt or in any place — the unjust ruler is hated,” he said. “Whoever defends the oppressor is his partner with him in oppression, and whoever is with the oppressed shares with him his reward from God.”

He broke rank with other Shiite clerics by criticizing President Bashar al-Assad of Syria, who is backed by Iran, and supported rule by the Kurdish majority in northern Iraq.

In another sermon, he spoke against the use of arms and said protesters should be willing to die for their cause: “Our strength is not in weapons; our strength is in martyrdom.”

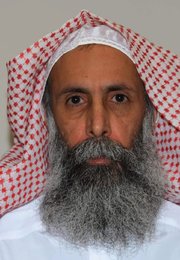

Slim and bespectacled, with a white turban and a salt-and-pepper beard, Sheikh Nimr was unflinching in his criticism of the Saudi royal family, calling its members “tyrants,” comparing them to hated villains in Shiite history and calling for their downfall.

“A crown prince dies, put a new crown prince! What are we, a farm? Poultry for them?” he shouted. “We don’t accept Al Saud as rulers. We don’t accept them and want to remove them.”

The Saudi authorities arrested him in 2012, and he was shot in the leg before being taken into custody. The government said that the police had come under fire while approaching, and images of Sheik Nimr wrapped in a bloody white cloth spurred more protests.

He was sentenced to death in 2014 in a trial that human rights groups and the United Nations have said did not follow due process.

Some analysts say that the arrest and trial of Sheikh Nimr — and the intense coverage by news media sympathetic to Iran — propelled his rise from a local figure into an international icon, a process completed with his execution, which made him a martyr to his supporters.

Shiite leaders from Iran, Iraq, Lebanon and elsewhere have lauded him as a hero and condemned his execution, and protesters have carried his photograph through streets of many cities. If Saudi diplomats return to their burned embassy in Tehran, they will find a street outside is now named after him.

“They gave the Saudi Shiites a martyr of their own,” said Abbas Kadhim, a senior foreign policy fellow at Johns Hopkins University. “He will be their martyr and their symbol.”

Source: