The Joy of Reading – by AZ

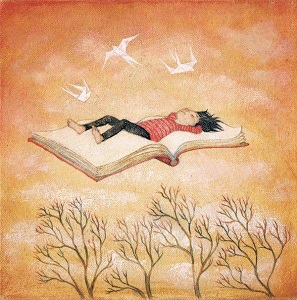

I had just taken to reading. I had just discovered the art of leaving my body to sit impassive in a crumpled up attitude in a chair or sofa, while I wandered over the hills and far away in novel company and new scenes… My world began to expand very rapidly, the reading habit had got me securely. — H. G. Wells

While I am becoming increasingly good at not getting any reading done, I sometimes do rue the now almost complete loss of my habit to read regularly. That habit that involved staring at first few words on the first page until first the lines and then the pages began to make sense, and then thinking about them until I had my own interpretation of what I read. The fact is that there is no substitute for reading a book even if, more than ever, we seem to be losing the knack of reading them. Instead, we have learnt the art of faking cultural literacy as Karl Taro Greenfield recently wrote in New York Times article, “What we all feel now is the constant pressure to know enough, at all times, lest we be revealed as culturally illiterate. What matters to us, awash in petabytes of data, is not necessarily having actually consumed this content first-hand but simply knowing that it exists.” What Greenfield says, though, is not something entirely new. Book lovers of the past also accumulated a lot more than they could read. Schopenhauer said some 170 years ago, “One usually confuses the purchase of books with the acquisition of their contents.”

reading them. Instead, we have learnt the art of faking cultural literacy as Karl Taro Greenfield recently wrote in New York Times article, “What we all feel now is the constant pressure to know enough, at all times, lest we be revealed as culturally illiterate. What matters to us, awash in petabytes of data, is not necessarily having actually consumed this content first-hand but simply knowing that it exists.” What Greenfield says, though, is not something entirely new. Book lovers of the past also accumulated a lot more than they could read. Schopenhauer said some 170 years ago, “One usually confuses the purchase of books with the acquisition of their contents.”

Recently there was a thread of posts on Facebook whereby people asked their friends to name the ten most favourite books they had read. When I was asked to do so, I first drew up a list of potential names. As I sat down to shortlist them I realised that I had unconsciously picked a number of books of which I had at best read just a small part but, on occasions, I had lied about reading. I am sure many other people have also been guilty of doing the same at various points in their life. My generation and a few generations on either side of mine are probably the generations in human history that have consumed the largest number of books because of books becoming more accessible and affordable than ever before, while we still had time and passion for paper.

Logically the free mass availability of ebooks should mean that now we read more books than ever before. But that is not the case because the perennial human desire to look more intelligent and informed than we are coupled with a surfeit of knowledge and text in the digital age has meant that we more and more lack the time and drive to engage with anything more than a few lines befitting tweets or Facebook status updates. Also the internet has made it so  much easier to pretend without having really experienced. The pleasure of reading that involved serenity, privacy, and contemplation is now a fading trade. The books that require true effort are read increasingly less. Last year’s Man Booker prize winner Eleanor Catton says, “Consumerism requiring its products to be both endlessly desirable and endlessly disposable cannot make sense of art, which is neither.” Books like Pride and Prejudice or War and Peace are not meant to be whizzed through. They are intended to deepen our soul and to discover the rush of excitement and recognition that occurs when we look up from a great book and think: yes, the world is like that.

much easier to pretend without having really experienced. The pleasure of reading that involved serenity, privacy, and contemplation is now a fading trade. The books that require true effort are read increasingly less. Last year’s Man Booker prize winner Eleanor Catton says, “Consumerism requiring its products to be both endlessly desirable and endlessly disposable cannot make sense of art, which is neither.” Books like Pride and Prejudice or War and Peace are not meant to be whizzed through. They are intended to deepen our soul and to discover the rush of excitement and recognition that occurs when we look up from a great book and think: yes, the world is like that.

I miss the good old days of sound reading habits when we kept our opinions, in any matter, to ourselves until we were sure what they were. How I wish I could find again the commitment to staring at first few words on the first page until first the lines and then the pages begin to make sense. How I wish I could rediscover the temperament to sit in the libraries imbued with a profound silence that made reading irresistibly tempting. In intimacy, with the tête-à-tête attention they want, books are not tools to withdraw from but rather to understand and interact with the world. Now, I have noticed, I have trouble sitting down to read. It is not a malfunction of desire but of focus; the capacity to calm my mind long enough to dwell in someone else’s world, and to let that someone else dwell in mine. And my distractions are rarely, if ever, of any enduring significance but the usual continuing frivolities.

Reading is the only art in which we let ourselves merge with the consciousness of another person. While we possess the books we read, they possess us also, filling us with ideas and feelings and, to that extent, becoming a part of us. The books help us grow by affording us access to experience other than ours. But for that to happen we need a certain calm, which is elusive in our world where every routine is tweeted and advertised on the Facebook. We are the product of a culture which makes reacting quickly more important than thinking. Books slow us down and that’s why we are wary of them. Where novelty is an imperative, books don’t matter because, by their nature, books are never new enough. I, for instance, am constantly preyed upon by the intrusion of the buzz, the murmur that there is something out there that demands my attention -something on email, twitter, facebook, or internet- when in fact it is nothing but the anxiety of our age. In a world that requires us to know everything instantly, it is difficult to give ourselves the space to contemplate.

That is where reading becomes so important, because it requires that space. Charles Bowden writes in his book, (Some of the Dead Are Still Breathing), “I cannot feel alert unless I push past the point where I have control.” William James once said, “My experience is what I agree to attend to.” These statements in the context of reading remind me that reading is an activity that helps us both escape and be engaged at the same time. You lose control but you are more in contact with yourself and more aware of where you belong in a world of limitless choices, prospects, and distractions.

“I would be most content if my children grew up to be the kind of people who think decorating consists mostly of building enough bookshelves.” ~Anna Quindlen

Source: