Indicting the Pakistani left: reflections on Jamal Naqvi’s biography – by Dr. Khalid Sohail

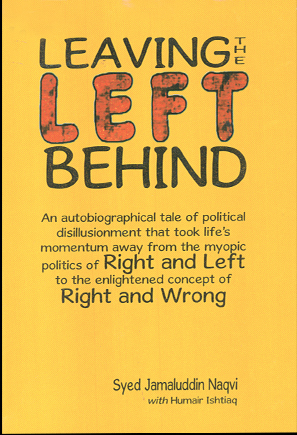

During my last visit to Vancouver my dear friend Saif Khalid strongly recommended that I read Professor Jamal Naqvi’s book Leaving The Left Behind and write my reflections. Once I started reading the book I could not put it down. I thoroughly enjoyed the book as it is an honest political autobiography of a dedicated Communist and a committed political activist. By reading that book I learnt so many new things not only about the history of Pakistan but also about the political struggles of the Communist Party of Pakistan.

Before I share my thoughts about the book let me make a political confession. I am not a Communist and I have never been a member of any Communist Party but I developed a keen interest in socialist ideas and ideals because my poet uncle Arif Abdul Mateen was involved in the Progressive Writers Movement in Pakistan.

In the last two decades I have also developed a keen interest in the psychology of creative personalities that include poets and philosophers, scientists and scholars, artists and mystics and especially reformers and revolutionaries. One of my books is titled Prophets of Violence, Prophets of Peace. In that book I have presented the psychological analysis of the biographies of political leaders of the 20th century who believed in social change. I reviewed the biographies of reformers like Leo Tolstoy, Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Dalai Lama, who believed in social change through peaceful means and also biographies of revolutionaries like Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh and Nelson Mandela, who believed in political change through armed struggle. While researching and writing my book I was fascinated to read that reformers were willing to sacrifice their own lives on the altar of social change but revolutionaries were also willing to take lives for their ideal of revolution. Many revolutionaries believed that the end justified the means.

During my research I was also fascinated how over the years and decades those political leaders transformed the political movement and how their movement changed them. The personal and philosophical changes were intimately woven with psychological and political changes. While reading those biographies I was also intrigued how those political leaders tried to balance their political lives with their marital and family lives. Once Nelson Mandela had mentioned to the bride of his comrade friend, “You are marrying a married man. He is married to his cause.” As a psychotherapist I am quite mindful how the wives and children of political leaders and political activists offer their sacrifices for the political ideals of their husbands and fathers.

I am sharing all these details about myself to highlight how much I enjoyed reading and reflecting on the political autobiography of Jamal Naqvi because that biography is intimately connected with the themes I have been following for a number of years and his struggles are close to my heart.

When I finished reading the book Leaving The Left Behind I experienced a feeling of profound sadness because Jamal Naqvi’s story is a sad story. It is a story of a genuine, honest and committed Communist Leader who fought for his ideas, ideals and ideology all his life. He worked hard and struggled hard and offered all the sacrifices he could offer for his cause. All his life he fought on many frontiers. He fought with repressive police, autocratic governments and brutal army. For his ideals he had to endure harassment, imprisonment, solitary confinement, even torture. It was not the fight of one week or one month or one year, it went on for decades. Jamal Naqvi was a marathon runner not a hundred meter sprinter. It was not the fight of one man, it was the fight of thousands of Communists who had a dream of creating a just and peaceful world for millions of poor working class people of Pakistan. But unfortunately that dream of a just and peaceful world turned into a violent nightmare.

It was quite painful for me when I read that at the end of his struggle, in the evening of his life, Jamal Naqvi experienced a breakdown. It was a breakdown of not only his physical health when he experienced a stroke, while still in police custody, but also a political breakdown, when he visited Moscow. In that process his wife also experienced a nervous breakdown. Reading that story I felt sad, profoundly sad.

If I had to summarize Jamal Naqvi’s life long story and struggle in one sentence I would say that it is a story of falling in and out of love with Communism. Jamal Naqvi fell in love with Communism when, as a teenager, he was inspired by his cousin who was a political activist.

He was fascinated by his charm and charisma and his ideology of Communism. He writes, “Our cousin Shafiq Naqvi was the President of the students union at Lucknow University, some 200 kilometers to the north-west. More importantly, he was the Secretary of the United Province [UP] chapter of the Communist Party of India (CPI). He later became the ‘whole-timer’ and had to suffer lengthy prison terms in India for his political beliefs and conduct. As a young lad, I was rather bewitched by what he believed in and the manner in which he would express it.

There was a touch of the rebel about him and to my young eyes he was the epitome of knowledge and intellect. He for sure interested me more than my course books. I wanted to be like him, a Communist.” (page 20) So when Jamal Naqvi became an adult and could freely make choices about his life, he followed the footsteps of his idealist Communist cousin. While keeping his political ideals close to his heart he also studied English Literature and became a teacher. Gradually teaching English Literature became his profession and Communism became his passion. Because of his commitment and dedication to his Communist ideals he joined the Communist Party of Pakistan and climbed up the ladder to become one of its well respected leaders. He writes, “My suspension from service lasted a good three years—from May 1975 to March 1978.

It was during the suspension period that I had the time to spend on a lot of Party activities after being promoted from the Central Committee to being a member of the Politburo, which was the ultimate decision making apparatus of the Communist Party.” (page 76) In the beginning he was not aware what sacrifices he might have to give for his cause but at each turn of his life he remained steadfast. As a Communist Leader of a party that was banned in Pakistan he had to hide many times to stay away from the eyes of police. He writes, “Both in Hyderabad and Karachi there were countless occasions when I had to take shelter in one of the hideouts and to arrange the delivery of a medical certificate to the college I was associated with at any given time.” (page 66).

There were times he could avoid the arrest but then there were other times he was put behind bars and he had to suffer. One of those times was when he went to help his comrade friend Nazeer Abbasi. He writes, “On July 30, 1980, I went to see Abbasi at his house in a squatter settlement around North Nazimabad in Karachi. It was something urgent that Abbasi needed to discuss and I had to take the risk of exposing his location in going to see him. As it turned out, it was one risk too many. As I knocked on the door, I was unaware of the suspicious movement behind me which Abbasi noted from inside the house and tried to escape from the back door.

Unaware of what was going on, I entered the house after knocking for a while to see Abbasi in the captivity of men in civilian clothes but with clearly commando looks. The house had actually been surrounded and there was no point trying to be smart. I was taken in custody as well and a search ensued of the house that was almost bare in its entirety. All they ‘recovered’ was some photographs of Jam Saqi, which was considered evidence incriminating enough to take us both in custody blindfolded and hand-cuffed. We were asked by one of them to identify us which we did. Incidentally, the words, “I am Nazeer Abbasi” were the last I heard anything from Abbasi.” (page 82)

During imprisonment, Abbasi was killed and Jamal Naqvi was tortured. One aspect of torture is described by him in these words, “…I was made to stand up while being tied to the ceiling with a chain around my neck. This continued for a good 24 hours. There was no relief and I could not move much as the chain would choke me the moment I would go light on my feet.” (page 88)

All of his life Jamal Naqvi offered sacrifices and remained loyal to his cause and faithful to his ideals. But in the evening of his life when he visited Moscow he became so disappointed and disillusioned that he said goodbye not only to his Communist Party but also to Communism.

While I am quite impressed and inspired by Jamal Naqvi’s personal sacrifices and political struggles I am not convinced by his conclusions as in those conclusions I see some generalizations and rationalizations. Let me explain myself. For me Jamal Naqvi has every right to conclude about his personal life and say I failed as a Communist Leader but I disagree with him when he makes one generalization and says that The Communist Party of Pakistan failed and then makes another generalization and says that Communism failed. Jamal Naqvi makes political and philosophical generalizations based on his personal frustrations, disillusionments and disappointments. By doing that he is unfair to all those members and leaders of Communist Parties all over the world who have been struggling and dreaming of a just and peaceful world.

As a psychotherapist I also feel that Jamal Naqvi comes to some emotional conclusions and then justifies them by rational explanations. In the discipline of psychology we call that phenomenon rationalization. Let me explain my impression. After forty years of struggles and sacrifices Jamal Naqvi faced his first major crisis when he experienced a stroke. He was partially paralyzed and became speechless while still in police custody. He writes, “It was during the court proceedings, in early September that I just lost control over my body. It was a stroke that had paralyzed the left side of my body. Besides, I also lost my power of speech.” (page 105) That was the beginning of the end of his role as a political activist and Communist Leader. From a psychological point of view I am of the opinion that enduring his imprisonment, solitary confinement and torture and death of his dear comrade friend got so intense that his body and mind could not take it anymore and he collapsed. He experienced a breakdown, a breakdown of his physical health and a breakdown of his ideals and in this process he also experienced a breakdown of his ideology.

I also wondered about the effect Abbasi’s death had on Jamal Naqvi’s psyche. After Jamal Naqvi was released from the prison he went to pay his respect to Abbasi’s grave. He writes, “ …the two of us had been picked up together from the hideout. Even if with paralysis and bad breath, I had survived the ordeal, but he was not lucky enough as life had been sniffed out of his young soul through excruciating torture. I needed to pay homage to the memory of the man who had sacrificed his life so that others could survive. To me, Abbasi was the symbol of all those who had lost their lives under the Martial Law regime.” (page 112) I wonder whether Jamal Naqvi, like many other friends and relatives who survive while their dear ones die, suffered from survivor’s guilt.

I also found Jamal Naqvi’s close relationship with his daughter Afshan quite interesting. Of all of his children he wanted her to walk on his footsteps and become a committed political activist and a dedicated Communist. But when Afshan came back from her trip of Moscow, she was utterly disappointed. Her description of her disillusionment was so convincing that Jamal Naqvi started having doubts in his ideals. He started questioning the role of Russian Communist Party. He lived with his doubts for a while but when he went to Moscow himself his disillusionment in Communism reached his climax.

Somewhere deep in his heart he was upset that Russian Communist leaders did not give him the respect and reverence he deserved. He was treated like any other Communist guest. They did not realize that Jamal Naqvi had some serious questions about the relationship between Russian Communist Party and the Communist Party of Pakistan and wanted to have a heart to heart talk with them. He wanted to ask them why did Russian Communist Party put pressure on Communist Party of Pakistan to support Imam Khomeni in Iran. So when he was ignored and his questions were not taken seriously, his pride in his ideals was shattered. He came back broken hearted. He writes, “

The flight on the way back [from Moscow} was quite uncomfortable. Physically everything was just the same, but intellectually I was a shattered man.” (page 161) That is when he fell out of love with Communism and then divorced it. After that emotional and political crisis, it took him some time to announce it publicly and say goodbye to his Communist Party and his Communist Ideology. He was also disappointed that his comrade friends in Pakistan did not try to stop him and did not plead with him to stay.

I mentioned earlier that I am not a Communist and have never been a member of any Communist Party. I am a Humanist who believes in human evolution. I believe that in the last couple of centuries

Biologists like Charles Darwin

Psychologists like Sigmund Freud

Sociologists like Karl Marx

Scientists like Albert Einstein

And

Philosophers like Jean Paul Sartre

have played a significant role in human evolution and our secular and scientific understanding of human condition.

Russian interpretation of Marxism was just one interpretation of Marxism made by Lenin and Stalin.

In my opinion effects of Karl Marx and his philosophy were not restricted to USSR. Those effects have been seen in many parts of the world, especially in Cuba and Scandinavian countries. There are so many countries in the world like Canada that has free health care for patients, free education for children, unions for factory workers and special economic rights for farmers that would not have been possible if socialist philosophy was not accepted by these communities and countries. That for me is a long term success of Marxism, Communism and Socialism. That is why I feel that for Jamal Naqvi to say that Communism failed is an overgeneralization and rationalization. In history, with passage of time, philosophies change and evolve. We need to see how any philosophy changed the world. I think Marxism was a great gift for humanity and it made this world a better place to live and work.

I agree with Jamal Naqvi that some Communists became rigid ideologues who were unable to accept any criticism but such Communists do not represent all Communists. In every organization and party there are some hard liners but they do not reflect the whole organization. I still feel that there are many socialists all over the world who believe that for developing countries the gap between the rich and the poor, the haves and have nots can only be decreased by socialism. I am one of them. I do not see any contradiction between socialism, democracy and humanism. I think these philosophies can complement each other and we can create socialist communities and countries through democratic means. I think socialism inspires us to take social responsibility and humanism helps us to see all human beings as members of the same family, the human family.

In the end I would like to say that in spite of my disagreements with some of Jamal Naqvi’s conclusions, I am very impressed and inspired by his political autobiography. I think that book should be read by all Communists, Socialists and Humanists of Pakistan. It is a scholarly written book and I would like to congratulate Jamal Naqvi for his honesty, sincerity, and integrity. Not very many political activists would have the courage to write such a book and make a sad confession, “The story that follows is the story of a life mostly spent chasing shadows…an utter waste.” Jamal Naqvi might consider his life story an utter waste but I am confident that many students of political psychology and leaders of political movements would find his story of offering sacrifices for his ideals very meaningful, impressive and inspiring.

Source: